Background

The Light That Failed is Kipling’s first novel, written when he was 26 years old, and therefore of considerable importance in the canon of his works. Since its initial publication in 1891 it has encountered a substantial body of negative, even hostile criticism. However, Jad Adams author of a recent (2006) Kipling biography, reminds us that the novel has stayed in print ever since its first publication, over a hundred years ago.

The story

The story centres on Dick Heldar – a thinly-veiled Kipling self-portrait – and his relationship with, and unrequited love for, Maisie, his childhood playmate, who was based on the real-life artist Flo Garrard, of whom more later. As children they are both under the cruel and repressive care of Mrs Jennet, where, even as a child, Maisie treats Dick with indifference. Dick later becomes a successful artist through his war-time illustrations, for London newspapers, of the Sudan campaign. (This was mounted in 1885, to defeat the Mahdi and relieve General Gordon at Khartoum.) In the Sudan Dick meets Gilbert Torpenhow, the correspondent of the Central Southern Syndicate, who is instrumental in spreading Dick’s reputation. They pledge friendship and promise to keep in touch.

Later, after Dick’s travels in Africa and the Orient, he hears from Torpenhow that his illustrations have made him famous, and this renews the friendship. Dick returns to London, meets Maisie again unexpectedly, and falls in love with her. Maisie, however, has artistic ambitions of her own, and rejects his passion to concentrate on her career, encouraged by her nameless companion, ‘the red-haired girl’, between Dick and whom there springs up a complex love-hate relationship. She is jealous of Dick’s attention to Maisie, but is secretly attracted to him. She makes a drawing of him, mocking his enslavement to Maisie, and vindictively destroys it.

Maisie and Dick begin work on their own versions of ‘Melancolia’ the symbolic figure in James Thompson’s poem “The City of Dreadful Night”, a key influence on the novel and discussed in detail later. Their competitiveness creates unresolveable personal and artistic conflict. Dick thinks himself the superior artist, convinced that Maisie has neither the insight nor ability to meet such a challenge. Throughout, Kipling sustains the novel’s one true lasting relationship, between Dick and Torpenhow. Dick has endured the earlier pressures of commercialism on his own artistic integrity, his fruitless passion for Maisie, and the conflict between Love and Art. Then he becomes incurably blind from the delayed effects of a Sudan war wound.

Emotionally distraught, Maisie leaves him. He is left alone in his blindness and privation, with only his artistic credo and dedication intact. He is finally drawn from the world of art to the world of action, once again on the battlefields of the Sudan. He is struck by a stray bullet, and dies in Torpenhow’s arms.

Critical responses

The novel has variously been described as sentimental, unstructured, melodramatic, chauvinistic, and implausible. Kipling himself said: ‘… it was only a conte—not a built book’. (Something of Myself p. 228). Relatively mild reproofs include Professor Carrington’s in his essay for the ORG who feels it is ‘not a good book, and not the best of Kipling’ but is also mindful that it is ‘never out of print.’ For Andrew Lycett (p. 286), another important Kipling biographer, ‘the novel’s major drawback is that it is a ‘grown-up’ novel by an emotionally immature man’.

J M S Tompkins (p. 12), the doyen of Kipling critics, states more probingly that any artist ‘cannot cope with all he knows’, and that Dick’s character is ‘blurred in consequence’; partly as a result of Kipling’s extremes of ‘exaltation’ or ‘chastisement’ in the presentation of Dick, and because there is less involvement in the character of Maisie.

Angus Wilson’s accusation (p. 156) of Kipling’s ‘blind self-flattering misogyny’ rather overstates the case in the view of this Editor, but perhaps contains an element of truth. Critic and biographer T R Henn has no truck with the novel’s ‘ponderous irony, Biblical phrases, Wardour Street diction, and jocularity of tone’ (p. 82). And it is hard not to detect a note of bile creeping into Lord Birkenhead’s comment on Captain’s Courageous (1896), that ‘the book failed for exactly the same reasons as ‘The Light That Failed… the characters are mere ciphers, who might with little loss to the reader, be called X,Y or Z’ (p. 311). He even goes so far as to describe The Light That Failed as ‘a rotten apple’ in ‘the teeming orchard’ of Kipling’s other published stories in 1890. (p. 123)

One could extend the catalogue of strictures, assertions and counter-arguments ad infinitum, and to little purpose. Readers will, after all, come to their own conclusions on these matters. The fact is that The Light That Failed has always suffered in comparison with Kim (1901), Kipling’s most famous and popular novel. The aim of these notes is to move it out of the shadows, and assess its qualities on their own literary merits, as well as considering its rich background and range of themes.

Cruelty and brutality

One recurrent critical theme does, though, merit closer consideration; the novel’s recurrent cruelty and brutality. Many critics and writers who are admirers of Kipling have had difficulties with this, both in this novel and in other works. J M Barrie and Henry James, for example, whilst recognising his enormous talent, could not accept the brutality and cynicism as they perceived them. George Orwell, in his famous Horizon essay on Kipling (Horizon 1942 in Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters Vol 2, Penguin Books 1970), acknowledged the realism of Kipling’s vision of war, seeing him as a prophet of late 19th Century imperial expansionism, and admiring the way the book captures the atmosphere of life at that time. But he echoes the charge of a ‘definite strain of sadism’ (p. 214), and the ‘hunger for cruelty’ (p. 222), to be confronted and answered.

The problem tends to arise in relation to three particular scenes: Torpenhow’s gouging out the eye of the Arab soldier in Chapter II; Dick’s manhandling of the Syndicate Head in Chapter III, and Dick’s orgiastic response to the machine-gunning of enemy troops in the final chapter. One might also add Dick’s generally unpleasant treatment of Bessie Broke, the artist’s model. His treatment of the Syndicate Head can be partly explained by the unjust and chaotic Copyright laws of the time [see the Note on Ch III Page 40 line 28]. Kipling’s own resentment over the treatment of artists and writers undoubtedly lasted throughout his life. There is a telling reminiscence, ironically paraphrasing his famous poem “Recessional”, in his autobiography Something of Myself (1937), where he refers to the surge of interest in his poetic juvenilia after he attained fame and success. He gave a schoolboy poem to a woman when he left school:

…who returned it to me many years later… I burnt it, lest it should fall into the hands of ‘lesser breeds without the (Copyright) law’.

We will return to these episodes later, in other contexts.

The incident with Torpenhow and the Arab soldier’s eye is a sadistic touch, this Editor believes, although Kipling might well have thought ‘After all, such things happen in war.’ It is also arguably redundant when considered against the background of the Chapter’s vivid and powerful battle scenes. However, Kipling doesn’t linger gratuitously over the detail. Torpenhow grapples with the soldier, reaching for the man’s face, clearly in understandable desperation. Soon after, he wipes a thumb on his trousers; ‘the man’s upturned face lacked an eye’. Even the battlefield carnage is reduced to a single charged sentence ‘the ground beyond was a butcher’s shop’. The simple omission of ‘like’, creating a visual metaphor out of a potential simile, is just one of myriads of quotable examples of the young author’s immediacy and sureness of touch.

Childhood influences

Whatever the flaws in Dick’s character and behaviour, Kipling carefully establishes a pattern of childhood influence and causation in Chapter I. Kipling readers will be familiar with the various accounts of the exile in England forced by their parents on the five year old Kipling and his three year old sister ‘Trix in 1871. This was a common practice amongst Anglo-Indian families to protect their childrens’ health and ensure that they had a thoroughly English upbringing. Rudyard and Trixie were placed in the foster-care of Mrs Sarah Holloway at Lorne Lodge, Southsea, later referred to by Kipling as ‘the House of Desolation’ where they endured six years of tyrannical harshness, an experience which marked him for life, and forms the basis for this Chapter.

In The Light That Failed Sarah Holloway becomes ‘Mrs Jennet’, whilst Dick is clearly the young Rudyard. This episode is also prominently fictionalised in a more-or-less contemporaneous story “Baa Baa, Black Sheep” (Wee Willie Winkie 1890) in which Kipling becomes ‘Punch’ and Sarah Holloway ‘Auntie Rosa’. Kipling refers bitterly, but with characteristic succinctness, to the repression of these formative years in Something of Myself: ‘I had never heard of hell, so I was introduced to it in all its terrors’.

Kipling leaves us in no doubt as to the effect on Dick, and himself as a child:

Where he had looked for love, she gave him aversion, and then hate. Where he growing older had sought a little sympathy, she gave him ridicule.

Dick’s sufferings and neglect teach him the power of living alone and of enduring schoolboy mockery, but set in motion an undercurrent of violence in his character. It is a reasonable assumption that for Kipling these experiences may account for the incidents of bullying and humiliation in some of the later schoolboy stories in Stalky & Co (1899). These are echoed in one brief passage in the novel:

Dick shambled through the days unkempt in body and savage in soul, as the smaller boys of the school learned to know, for when the spirit moved him, he would hit them, cunningly and with science.

The final phrase hints at the sadistic element that is taking root within him. In Chapter III, as an adult, prompted by the Syndicate Head’s emphasis on how much he owes them for spreading his reputation, Dick is reminded of ‘certain vagrant years, lived out in loneliness and strife, and unsatisfied desires.’ There is frequent testimony in Kipling’s writings to the persistent sense of pain and suffering which influenced the darker side of his own and, therefore Dick’s, character. In a 1907 address to McGill University he says:

There is a certain darkness and abandonment which the soul of a young man sometimes descends – horror of desolation, abandonment and realised worthlessness, which is one of the most real of hells in which we are compelled to walk.

The early descriptions of Dick’s character from The Light That Failed are a kind of fictional shorthand; we have to take Kipling’s word for them, in the absence of narrative. But they surely explain, even if not wholly justifying, the troublesome aspects of Dick’s behaviour, and are at the heart of Kipling’s artistic vision and practice. The portrait of Dick, consequently, is unflinchingly ‘real’ and honest; an unpredictable, arrogant, immature young man, but one who feels deeply and suffers profoundly. All else stems from this. Kipling could be no other kind of writer.

Because “Baa Baa, Black Sheep” dramatises the Southsea experiences so vividly, the final lines of the story offer perhaps the most eloquent expression of the influence of these years onThe Light That Failed and on much else of Kipling’s work. In imagery drawn from the Bible and Bunyan, and directly relevant to the novel, he writes:

…when young lips have drunk deep of the bitter waters of Hate, Suspicion and Despair, all the Love in the world will not wholly take away that knowledge; though it may turn darkened eyes for a while to the light, and teach Faith where no Faith is.

Dick, therefore, is merely being true to his own nature and his artist’s code when sardonically describing the graphic realism of his illustration of the soldier called “His Last Shot”, which he is forced to clean up to make it acceptable to the public. Dick may even have had Torpenhow’s life-and-death struggle with the one-eyed Arab in mind at this point:

It was brutal, coarse, violent — Man being naturally gentle when he’s fighting for his life.

The remark both encapsulates Kipling’s own credo, and the conflict between the the claims of Art and Commercialism which informs so much of The Light that Failed.

‘Maisie’ and ‘Flo’ Garrard

If Kipling’s childhood experiences at Southsea are one key autobiographical influence on the novel, the other is the relationship between Kipling and Florence (Flo) Garrard, the inspiration for the character of Maisie. Kipling’s unfulfilled passion for Flo, and her rejection of him, form the emotional core of the book.

Any first-time Kipling student with little or no knowledge of his works, and reading his autobiography Something of Myself, will find no mention of Flo nor of the devastating effect of his love for her; it is as if they had never existed. The title of the autobiography is self-revelatory, and its structure equally so, as so much of his short fiction, where there is rigorous selectivity and withholding of detail to create an effect. We simply, in this case, don’t get the whole story.

According to Something of Myself, written in the last year of his life, the germ of the novel: ‘lay dormant till my change of life in London woke it up’. (p. 228) The hibernation period dates, perhaps, from 1878 when he saw and never forgot Jean Paul Pascale-Bouverie’s painting of ‘Manon Lescaut’ at the Paris Exhibition, based on the 18th Century novel by Abbé Prévost. He described the resultant The Light That Failed as a: ‘sort of inverted, metagrobolised phantasmagoria based on Manon‘. Metagrobolise is derived from the French of Rabelais, meaning to ‘puzzle’ or ‘mystify’. The adjective may just about pass muster as a clue to Kipling’s emotionally confused state of mind when writing the book, as may ‘my change of life in London’ when in 1890 he met Flo again after an absence of 8 years. Phantasmagoria means either a dreamlike series of illusory images or an early optical illusion show. Both definitions reflect Dick’s mental state in his latter days, the episodic structure of the novel, and its creative use of visual ‘moments’.

In 1877 Alice Kipling returned to England to take the young Rudyard away from Southsea to become a pupil at the United Services College at Westward Ho! In 1880 Kipling came to Lorne Lodge to fetch Trixie. It was here that he met and fell in love with Florence Garrard, a year his senior.

She had been born in Kensington on January 31 1865. Her family owned the famous London jewellery firm, Garrard and Co., but her father turned his back on the business, and joined the army. He retired on half-pay in 1865, but failed to settle and took the family to France. Florence seems to have lived a somewhat peripatetic existence, often in hotel rooms, and having only a fragmented education. So her arrival at Lorne Lodge to Mrs Holloway’s care, after Rudyard’s departure, was a fateful co-incidence, but not too surprising under the circumstances. She was far more sophisticated and unconventional than Rudyard, and was exactly the ‘long-haired grey-eyed little atom’, as Maisie is described in the novel. She dressed carelessly, but the adult Trixie in a 1940 letter to her niece Elsie Bambridge (quoted in Andrew Lycett, p. 100) remembers her ‘beautiful ivory face, the straight slenderness of her figure and the wonder of her long hair’.

The immediacy of Rudyard’s encounter with Flo in London, and its effect on him, are vividly reflected in his description of Dick’s meeting with the adult Maisie in Chapter IV page 56 of the novel. Dick is leaning on the Thames Embankment wall when:

…a shift of the fog drove across Dick’s face the black smoke of a river steamer at her berth below the wall. He was blinded for a moment, then spun round and found himself face to face—with Maisie. There was no mistaking. The years had turned the child into a woman, but they had not altered the dark grey eyes, the thin scarlet lips, or the firmly-modelled mouth and chin; and, that all should be as it was of old, she wore a closely-fitting gray dress.

This is almost cinematic in style, as befits Kipling’s life-long interest in photography and later in the moving image. For the reader to be told that: ‘Dick’s body throbbed furiously and his palate dried in his mouth’ is in a sense redundant; the emotion is all in the visual recall. Kipling almost certainly never forgot the meeting with Flo; and one wonders if the artist in him recognised the ‘phantasmagorical’ quality of the moment, and perhaps used it again in the story “Mrs Bathurst” (Traffics and Discoveries 1904) when Hooper recalls the effect of seeing Mrs Bathurst alight from a train at Paddington in a ‘Magic Lantern show’.

But the more ardent Rudyard became, the cooler Flo’s response. For almost two years they maintained a desultory correspondence until in the autumn of 1882 the sixteen-year-old Rudyard returned to India, and launched upon his journalistic and writing career.

Florence trained at the Slade School of Art in London and the fashionable Academie Julienne in Paris, becoming quite a successful portrait and landscape painter and a forceful character, with a fondness for cats. A self-styled ‘Chelsea artist’ she had exhibitions in the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy. Her sketch book revealed her Bohemianism in a series of drawings, cartoons and caricatures, to which Rudyard later contributed over a packed few days after his return to England in 1889, when he was still only twenty-three, and Florence twenty-four.

Rudyard visited her at her London house where she was living with Mabel Price, the model for the red-haired girl in the book, a fellow student of Flo’s at the Academie and daughter of an Oxford don. She too enjoyed some success as an artist, with a painting exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1889.

Kipling could not compete with their intensely close relationship, which may well have been a lesbian one. It is not certain, however, if Kipling knew this or not, guessed it, or refused to acknowledge it. Flo treated his literary success and his amorous emotions with wounding indifference. The note to the Heading poem “Blue Roses” for Chapter VII, which was dedicated to her, illustrates the contempt that she later expressed to a close friend and companion, for him, for the poem, and for the novel, which was first published in January 1891. She lived on and died on January 31 1938, two years after Kipling, aged 73, after a moderately successful career as a painter.

The term ‘relationship’ is patently inappropriate to characterise such a one-sided series of encounters. The artist in Kipling, however, superseded the lover enough for him to realise that it would be inadequate as the theme for a novel. Maisie and Dick, therefore, do have a relationship, adversarial, unsatisfactory, moving at times and ultimately doomed to failure, but at least a viable subject for fictional narrative.

There is, to this Editor, a tantalising if highly speculative postscript to all this. In her later years, Florence Garrard wrote a strange cartoon-like illustrated story, describing her time in prison after being arrested for trying to paint outside the Houses of Parliament. It was called Phantasmagoria, the same expression that Kipling used of The Light That Failed in Something of Myself (p. 228).

Did Kipling know of the existence of Florence Garrard’s Phantasmagoria and deliberately use the expression when writing of The Light that Failed in the last year of his life? Had he followed Flo’s career over the years? Was there the merest trace of conscience or regret on the part of either of them, with the long passage of time? Perhaps, but we shall never know.

Publishing history

As David Richards, the latest Kipling bibliographer, has explained, the publishing history of The Light that Failed is far from straightforward. Over two years, four versions of the story appeared: in twelve chapters with a happy ending; in fifteen chapters with a sad ending; in fourteen chapters with a sad ending; and in eleven chapters with a happy ending. The hardback ‘Standard’ version, ending in Dick’s death, is described in a prefatory note as ‘The Light that Failed as it was originally conceived by the writer.’ To understand the background, we must go back to Kipling’s arrival in England to forge a continuing and successful literary career.

He arrived in London in 1889, a few days before Mrs Edmonia [‘Ted’] Hill, an American friend from Indian days, whom he had met in Allahabad in 1887. Earlier in the year he had travelled with her and her husband Prof ‘Aleck’ Hill, from Calcutta to San Francisco, and stayed with her parents in Beaver, Pennsylvania. Mrs Hill came with her sister Caroline Taylor, to whom Kipling became engaged for a time. They set him up in rooms in Villiers Street across the road from Charing Cross Station in the heart of London, and then left for India. He corresponded frequently with them until 1890. Villiers Street is clearly the setting for Dick’s room in the novel, as is the London skyline from his window.

Kipling was never at ease with women of his own age, and his engagement to Caroline came to an end with Florence Garrard’s arrival on the scene. Kipling was now experiencing real literary fame, and it soon became obvious that a novel was expected. The one he had planned never appeared in print.

The Book of Mother Maturin

Since 1885 he had been devising a novel of Indian low-life called The Book of Mother Maturin, the manuscript of which arrived in London by mail, sent by his parents. Its whereabouts remain the last great Kipling mystery, although it is thought to have been in existence after 1900. In July 1885 Kipling wrote a Letter to his Aunt Edith MacDonald that it was going to be:

‘not one bit nice and proper’ … ‘it carries a grim sort of moral … it tries to deal with the unutterable horrors of lower-class Eurasian and native life as they exist outside the reports’.

Some of the intended material from Mother Maturin eventually found its way into Kim (1901). It had all the hallmarks of a controversial work, perhaps too much so for the Victorian reading public, accustomed though they were to realism and even sensationalism in their fiction. Even the brief scenario we have indicates the uncompromising side of Kipling as a writer, the modernity, almost, in the refusal to observe literary conventions, and his honesty in describing life’s unpalatable truths. The same spirit informs much of The Light That Failed.

Wolcott Balestier

Rudyard had been struggling with the first draft of The Light That Failed, but managed to meet his deadline of August 1890. It is at this point that Wolcott Balestier, Kipling’s American future brother-in-law, although posthumously so, comes into the story.

Balestier was the eldest of four children; his sister Carrie would later marry Kipling. He came from a prominent East Coast family with homes in New York and Brattleboro, Vermont, where Carrie and Rudyard lived for a while from 1892-1896. The American period produced Kipling’s only other novel solely under his own name, apart from The Light That Failed and Kim, Captain’s Courageous, which has an American setting and is partly an admiring tribute to certain American values.

After limited success as a writer, Balestier, an unconventional character who only lasted a year at Cornell University, drifted into journalism, becoming editor of a low-brow magazine called Tid-Bits, published by John W Lovell and Company. In 1888 he arrived in London on behalf of Lovell to court British authors and encourage them to sign up with firms like his. Because the regulations on copyright protection in the United States were rather looser than those in Britain, American publishers had been able to pirate foreign authors by publishing their works without permission, and without any payment of royalties. Lovell wanted to pre-empt new copyright laws, which were in prospect, by sending agents like Balestier to acquire rights in Europe.

It was soon after this that the paths of the man from Vermont and the successful young author would cross. When they did, it was the start of a close, albeit short-lived, friendship and literary partnership. Balestier could get things done. He was a man after Kipling’s own heart. He also combined a strong business sense with genuine literary understanding, and quickly made his mark in London. Carrie arrived there in 1889 and by 1891 had met and taken to Kipling.

During this crucial period, Kipling was becoming ill with stress and overwork. He was trying to cope with The Light That Failed, revising the collection of stories Wee Willie Winkie for publication, and working on another collection called The Book of Forty-Nine Mornings. He had also been engaged in a dispute with the publishers Harper and Brothers over the rights to some of his stories, and an attack on him in one of their magazines. Harpers backed down in the dispute, almost certainly thanks to Balestier’s intervention and support. He persuaded Kipling to abandon Forty Nine Mornings, and enabled the American publication, through Lovell, of Barrack-Room Ballads in 1890. That collection was dedicated to Wolcott Balestier.

Alternative versions

There has been considerable debate as to exactly how the different versions of The Light That Failed came to be published. Andrew Lycett, however, is unequivocal on the matter (p. 228):

Balestier also suggested Rudyard should put out two versions of The Light That Failed – his original ‘sad’ story, which would be published in volume form by the United States Book Company (the latest incarnation of the financially troubled John Lovell company) in the United States, and Macmillan in London, and a shorter alternative, bringing Dick and Maisie happily together, which would be easier for him to syndicate.

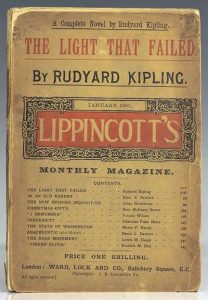

The upshot was that the version with a ‘happy ending’ was published in Lippincott’s Magazine in January 1891. Lippincott’s was a popular journal, first published in Philadelphia in 1886, with a high reputation and with circulation in Britain, the USA, and Australia. It featured literary criticism, general articles and original creative writing. It had recently had best-sellers, with Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novel The Sign of Four and – more controversially — The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde.

Kipling’s contribution was eagerly anticipated by its editors, and sold well in New York and London. This illustration shows the cover of the London version, which sold for a shilling (five pence in modern currency). But the story hardly enhanced his literary reputation. The original and longer ‘sad’ version was published by Macmillan in March 1891, with the full fifteen chapters; Chapter VIII and Chapters XIV and XV did not appear in the shorter version. The fifteen-chapter ‘sad’ version is now seen as the ‘standard’ text, and is the subject of these notes.

Kipling’s contribution was eagerly anticipated by its editors, and sold well in New York and London. This illustration shows the cover of the London version, which sold for a shilling (five pence in modern currency). But the story hardly enhanced his literary reputation. The original and longer ‘sad’ version was published by Macmillan in March 1891, with the full fifteen chapters; Chapter VIII and Chapters XIV and XV did not appear in the shorter version. The fifteen-chapter ‘sad’ version is now seen as the ‘standard’ text, and is the subject of these notes.

It is believed by some critics that in addition to Balestier’s view, Alice Kipling, the author’s mother, pressed him to go for a happy ending, which Kipling himself genuinely regretted. This tends to be the view of this Editor, and is borne out by the emphatic prefatory note at the head of the Standard Edition: This is the story of The Light That Failed as it was originally conceived by the writer.

However, the Dedicatory poem “Mother o’ Mine, O Mother o’ Mine” suggests that in insisting on the ‘sad’ ending Kipling felt some guilt at having betrayed his mother’s wishes. In this context, Philip Mallett (p. 58) subscribes to the neo-Freudian belief that:

…the love Kipling/Dick is looking for is essentially maternal … the story ends with Torpenhow on his knees, holding Dick’s body in his arms, in a presumably unintended parody of the Pieta.

In an oddly co-incidental way, the two versions of the novel can be said to echo Dick’s awareness of the conflict between ‘real’ and ‘commercial’ over the issue of the painting “His Last Shot”.

Wolcott Balestier died of typhoid in Dresden on December 6 1891, having collaborated with Kipling on The Naulahka, a novel largely neglected since by the general reader, but important in relation to The Light That Failed, as we will discuss later. It was published in 1892.

Such was the depth of affection and admiration between the two men that Kipling’s dedication to the Barrack-Room Ballads became his tribute to Balestier. The poem, written in eloquent and vigorous heptameters, ends:

Beyond the loom of the lone last star, through open darkness hurled,

Further than rebel comet dared or hiving star-swarm swirled,

Sits he with those that praise our God for that they served His world.

Carrie and Rudyard married in January 1892.

The ‘happy ending’

The ‘happy ending’ is generally derided by the critics as being incompatible with the thrust of the story as a whole, the characters of Dick and Maisie, and the nature of their relationship. The quality of the writing has also been criticised. In the view of this Editor, some of the cliche-ridden romantic exchanges seem hardly the high watermark of Kipling’s prose achievement. Nevertheless, however threadbare the love dialogue may be, this version merits some scrutiny.

The text does not, as one might reasonably expect from the derisive comments of the critics, end with Dick and Maisie in a mutually adoring embrace. Maisie leaves Dick, temporarily grief-stricken in the midst of her happiness at the vicious defacement of his painting that Dick cannot see. Apart from the fact that her departure is permanent in the Standard edition, both versions are very similar at this point in the story.

The final section has Torpenhow returning with news of a correspondents’ reunion in his rooms to discuss a return to the Sudan. Dick assures them he hasn’t ‘turned his back on the old life yet’. The gathering becomes noisy with shouting and singing, the room ‘heavy with tobacco smoke and the fume of strong drink’. Dick’s ‘poor second-hand gladiator’ jibe is ‘pretended scorn’ mingling admiration and regret that he cannot accompany them.

When Torpenhow stops Cassavetti singing the ‘Battle Hymn’ with the words ‘We’ve nothing to do with that. It belongs to another man’. Dick concludes the story with an emphatic ‘No … the other man belongs.’ In short, and surprisingly, it ends not with images of romantic bliss, but of the old virtues of war as adventure, and male camaraderie.

The Standard version’s ending, however, has not escaped critical censure either. Dick’s return to the Sudan has been regarded as over-sentimentalised or melodramatic. It could also be described as implausible, with Dick – given the nobility of his character – unlikely to be willing to risk the lives of his friends to take him back to the war-zone.

Opinion will doubtlessly continue to work against the ‘happy’ version. But it is interesting to note that that the ‘original’ version did not altogether disappear in this one, indicating, perhaps, where Kipling’s allegiances really lay.

Kipling and the Aesthetes

A study of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) and The Light That Failed (1891) opens up illuminating comparisons between the two in relation to the conflict between Kipling and the Aesthetic movement, and the dualities and contradictions within Kipling the man and artist.

Both novels, although so very dissimilar, focus on the themes of Art and the role of the Artist. Paintings as central symbols, which are ultimately destroyed, are a common feature. Dorian’s portrait is a fantasy image, which grows increasingly monstrous as his corruption increases, but his outward beauty remains unimpaired and ageless until the very end of the story. Dick’s “Melancolia” is a ‘real’ painting, based by Kipling on Albrecht Durer’s engraving. This was the basis for James Thompson’s original description of the figure in his poem “The City of Dreadful Night”, which outwardly expresses his artistic soul.

There are frequent references to the soul in both books. Basil Hallward, the painter of Dorian’s picture, fears the consequences of too much self-revelation if it appears publicly:

The reason I will not exhibit this picture is that I am afraid that I have shown in it the secret of my own soul.

(Complete Works of Oscar Wilde ed. Vyvyan Holland, Collins 1989 page 21)

And in a warning against the obsessiveness of Art, but with an implied homoerotic sub-text, and referring to his first meeting with Dorian, he declares:

I knew I had come face to face with someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself.

Dick’s inner tensions early in the novel are between the lure of commercial success and the need for artistic integrity. Torpenhow’s criticisms of Dick’s desire for the accumulation of money, carry both Biblical and Faustian overtones:

I don’t care to profit by the price of a Man’s soul — Dick’s soul is in the bank.

Both Dorian and Dick have, in their own ways but to different degrees, made pacts with the Devil, but Dick’s attitude changes profoundly, and he preaches his doctrine to Maisie:

You mustn’t mind what other people do. If their souls were your souls it would be different. You stand and fall by your own work remember.

DC Rose provides some fascinating reflections on the two works:

Hallward’s portrait of Gray is his masterwork … as Heldar’s ‘Melancolia’ is central to the plot of The Light. Heldar paints the piece while going blind, sustaining himself with whisky … His sight fails soon after the picture is finished and his model, who hates Heldar ‘emptied half a bottle of turpentine on a duster and began to scrub the face of the Melancolia viciously … She took a palette knife and scraped, following each stroke with the wet duster. In five minutes the picture was a formless, scarred muddle of colours.’ In Kipling we have a picture that is destroying its artist. In Wilde we have a picture that destroys its model.

(‘Blue Roses and Green Carnations’ KJ 302 p. 33)

It is interesting to note the difference between the descriptions of the destruction of the two paintings. Dorian sees a palette knife handy and Wilde simply states ‘He seized the thing and stabbed the picture with it’. One feels Kipling’s desire for authentic detail, however, extends as much to the destruction of a work of art as the creating of it. The quotation omits the small but signficant touch that the initial smudge was not enough; hence Bessie’s use of the palette knife.

The animosity towards Wilde and the Aesthetes was both moral and artistic. Kipling had made an earlier contribution to the debate with the poem “In Partibus” for the Civil and Military Gazette in 1889.

There are further jibes in the poem at ‘long haired things/ in velvet collar rolls’, who ‘moo and coo with women folk/about their blessed souls’. This seems mean-spirited stuff, with Wilde clearly in mind, and appearing all the more so when recalling Wilde’s rather more generous, albeit later, assessment of Plain Tales from the Hills. Kipling’s scorn for the Aesthetes was still intact 38 years later in Something of Myself (p. 219) as his reference to ‘the suburban Toilet-Club school favoured by the late Mr Oscar Wilde’ confirms.

“In Partibus” (see the notes on the poem in this Guide) attacks what Kipling sees as the derivative second-hand nature of Aesthetic theory. The same idea recurs in two later celestial fables, “The Conundrum of the Workshops” (1890) and “Tomlinson” (1891). In the latter the Devil derides the eternal quest for new artistic theories with his insistent variant refrain “It’s pretty but is it Art?”:

The tale is as old as the Eden Tree — and new as the new-cut tooth—

For each man knows ere his lip-thatch grows he is master of Art and Truth;

And each man hears as the twilight nears, to the beat of his dying heart

The Devil drum on the darkened pane ‘You did it, but was it Art?’

One wonders here if the phrase “lip-thatch” is a rueful allusion to the premature arrival of his own youthful moustache. The Devil also makes an appearance in “Tomlinson”, a poem about a young man-about-town, now dead, who had committed a double-sin; fornication with another man’s wife, and reliance on received bookish opinions. Such men, as Andrew Lycett puts it, ‘manage to lose their souls’:

Then Tomlinson he gripped the bars and yammered “Let me in —

“For I mind that I borrowed my neighbour’s wife to sin the deadly sin”

The Devil he grinned behind the bars, and banked the fire high:

“Did ye read of that sin in a book?” said he; and Tomlinson said “Ay!”.

When The Picture of Dorian Gray first appeared, W.E Henley’s assistant Charles Whibley, in the Scots Observer of July 1890, whilst praising Wilde’s ‘brains, art and style’, attacked the book as written for ‘outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys’.

William Ernest Henley, poet, playwrite, critic and publisher, was the leader of the counter-decadence of the late 1890’s so his involvement in the whole anti-Aesthetic saga is not surprising. He was the epitome of Victorian imperialistic views and hearty masculinity. He was also a periodical editor of distinction and a man of substantial literary cultivation. He edited the Scots Review — later the National Review (1884-94), which published Kipling’s “Danny Deever” in 1887, enhancing the reputation of both publisher and author. His familiar wooden leg, arising from an amputation caused by tuberculosis, made him the model for Stevenson’s Long John Silver in Treasure Island. The final lines of his most famous poem “Invictus” read:

It matters not how strait the gate

How charged with punishment the scroll

I am the Master of my fate

I am the Captain of my soul.

The poem was written in 1875, so we may assume Kipling’s familiarity with it. In any case, its spirit of male courage in the face of adversity would have greatly appealed to him — and to Dick Heldar.

In such a context we are faced with the paradoxes within Kipling the man and Kipling the artist. His hostility to Wilde and his like seems strange in one sense, bearing in mind his close youthful relationships with his aunt and uncle Georgina and Edward Burne-Jones and the liberal Pre-Raphaelite circle. He was later to describe his visits to them in his childhood as ‘a paradise which I verily believed saved me.’ (Something of Myself p.11) His distaste for homosexuality, however, remained unwavering.

Here, then, we have a young man resolutely set against membership of the literary establishment, who rejected all honours offered him, yet was to accept the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907; he was the first Englishman to receive it, and became one of the nation’s most revered literary figures. Allan Massie sees Kipling as:

…a highly self-conscious artist, reared in the shadow of the Pre-raphaelite brotherhood, who nevertheless despised artistic coteries and preferred to associate with men of action.

(The Literary Review Jan 1998; review of the new biography of Kipling by Harry Ricketts)

And John Palmer, quoted earlier, ironically describes Kipling’s art as:

…as formal as the Art of Wilde or the Art of Baudelaire, which he helped to send out of fashion, despite being contemptuous of literary formality.

(Rudyard Kipling’, Nisbet 1928 edition p. 14)

So, despite his so-called vulgarity and lack of ‘style’, and his shock-of-the-new realism, we have a painstakingly disciplined writer for whom dedication to the craft was essential for the creation of the art. Later in life he declared in Something of Myself (pp. 72-3):

There is no line of my verse or prose which has not been mouthed till the tongue has made all smooth,and memory, after many recitals, has mechanically skipped the grosser superfluities.

From all this emerges the character of Dick Heldar in The Light that Failed; the rebel and outsider; the individualist loyal to his own credo; the true artist unable to quite break free from the world of male camaraderie and action.

Kipling and the Arts

Painting and the visual arts were an important part of Kipling’s younger life, as one would expect with Lockwood Kipling, a distinguished artist, illustrator and designer, as his father. Lockwood, with his wife Alice, moved to India in 1865, the year of Rudyard’s birth, as a teacher in the JeeJeebhoy School of Art in Bombay (now Mumbai). Later Lockwood became curator of the Lahore Museum, and made an appearance in Kim as the Curator of the ‘Wonder House’. He illustrated Kim and the Jungle Books, as well as working on decorations for the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Given this background, a novel from Rudyard with a painting theme was probably inevitable sooner or later. That it was sooner was probably due to the power of these influences and the contact with illustrators which his journalistic career brought him, as well as his frustrations with Flo Garrard. As a child he would have been familiar with his father’s studio, the smell of oils and paints, the feeling of modelling clay and so on. These sense impressions find their way into The Light that Failed, so that it becomes, in the strictest sense, a colourful novel.

Kipling frequently describes his craft in visual terms; tone, brushwork and background and so on, and casually stated that to commit something to memory:

I rudely drew what I wanted to remember. (Something of Myself p. 230)

The writing of the stories in Rewards and Fairies (1910) is described as:

working the materials in three or four overlaid tints and textures…it was like working lacquer and mother of pearl, a natural combination. (Something of Myself p. 190)

The nature and creation of art, and in particular, the art of painting, is explored in the novel in three identifiable strands: the notion of an associated work ethic, the concept of artistic integrity, and the fascination for technique and process, which was to last a lifetime. In the penultimate Chapter of the novel he writes:

A man may forgive those who ruin the love of his life, but he will never forgive the destruction of his work. (p. 256).

Work, sacrifice, and the Law

Indeed the theme of work; of making, doing, building, runs throughout a great deal of Kipling’s oeuvre. Clara Claiborn Park, in KJ 319 quotes C S Lewis as saying (Kipling’s World, Selected Literary Essays CUP 1969 page 235): ‘It was Kipling who first reclaimed for literature this enormous territory’. Thus it can be said that he foreshadows writers like Arnold Bennett and DH Lawrence, to whom working life is central.

The idea of sacrifice and dedications is of major importance in the novel, although Dick doesn’t forget his early poverty, or advocate it for its own sake. He tells Maisie:

‘You must sacrifice yourself, and live under orders, and never think for yourself, and never have real satisfaction in your work, except just at the beginning, when you’re reaching out for a notion.’ (Ch. VII p. 107)

This austere doctrine has affinities with Kipling’s own concept of a personal ‘Daemon’ or inspiration outside oneself, to which one has to submit. The idea is developed further when Maisie recalls the words of her teacher Kami who stresses the importance of: ‘the conviction that nails the work to the wall’. (Ch XIII p. 212)

Shamsul Islam’s perceptive book on Kipling’s Law makes little direct reference to the novel, but what he says is highly relevant to it. Here, he could be discussing Dick himself, struggling to obey a natural law of survival, despite his tragic end:

Man’s victory lies in the struggle which he puts up against darkness, chaos and disorder. In the ultimate analysis Kipling’s is a very positive message. (Ch. 4)

Shamsul Islam (Ch. 5) sees the Law as a complex association of ideas drawing on moral, cultural and religious influences. Also, he itemises his notions of Kipling’s ideal man, which we slightly paraphrase :

-

- a man of honour and strong character

- who knows his job thoroughly

- who is devoted to it above all else

- with a strong sense of responsibility in all circumstances

- who is basically a man of action

- and who is capable of love, suffering and self-sacrifice

Given the odd exception, perhaps, and allowing for the possibility of human failings, this seems to this Editor a pretty fair summation of Dick’s character. Dick refers to the Law on more than one occasion, preaching here to a sceptical Maisie about self-sacrifice, and expressing Kipling’s idea of the Law as something natural and inevitable in human affairs:

“How can you believe that?”

“There’s no question of belief or disbelief. That’s the Law, and you take it or refuse it as you please.” (Ch. VII p.107)

The hectoring side of Dick’s character surely plays some part in the ultimate failure of their relationship. Maisie’s independence and her own self-containing loneliness, exacerbate Dick’s thwarted longings, forcing him into the unsustainable dual role of lover and teacher. He coaches her in line, form and colour, but his desire to help and protect her conflicts with his own artistic dedication, and widens the gulf between them. He is often brutally, if penetratingly, honest about her work:

‘Sometimes there’s power in it, but there is no special reason why it should be done at all’. (Ch. VII p. 98)

Dick even defines love in artistic terms when he says:

‘Love is like line work; you must go forward or backward, you can’t stand still’. (55).

This was hardly a recipe for romance or domestic bliss. His longing for Maisie and his love of Art become entwined into an illusory love, inconceivable outside their artistic relationship, and thus doomed to failure.

Techniques

Kipling’s abiding interest in technical process, and the crafts of making and doing is unique amongst English writers, and is almost a theme in itself, running through the body of his work. Perhaps its most notable manifestation is to be found in the complex later story “Dayspring Mishandled” (Limits and Renewals 1932) in which Manallace’s Chaucerian forgery, as an act of revenge against Castorley, the Chaucer expert, is described stage by stage in detail. This display of skills is crucial to the story, as it is essential that the reader – like Castorley – accepts the forgery as a credible deception. The extent of such knowledge of a range of processes in The Light that Failed is demonstrated through the many examples we have noted, chapter by chapter.

One key incident was Dick’s description of his picture ‘His Last Shot’. Dick tells how he has pipeclayed the helmet image to clean up the look (see Chapter IV p. 49 and Chapter XV p. 271); but Kipling adds the information that the technique is: ‘always used on active service’ and is ‘indispensable to Art’ (56).

Perhaps the most important instance is Dick’s account in Chapter VIII of the painting inspired by the ‘Negroid-Jewess-Cuban’ woman on the Lima to Auckland cargo boat in his roving days. She will make a re-appearance in this essay, but for the moment her interest is as a sort of ‘daemon’. Kipling dwells on the process with great energy and particularity of detail. Not only does he give us the approach to the painting but the inspiration and motivation. The excitement of sea travel, the likelihood of storm danger, and the fear of death, all contribute. Above all there is the woman’s sexual attraction, heightened by the fact she is always close to him when working and mixing his paints. The challenge of the limited choice of paint is also a factor; only brown, green and black ship’s paint is available. Kipling’s implication here is that this will give the right elemental quality to the picture.

Colour

Dick is also inspired by Poe’s poem “Annabel Lee” (Ch. VIII p. 131) to make creative use of the three colours, such as green for ‘the green waters over the naked soul’ of the drowning woman. (Ch. VIII p.132) The choice of such dramatic subject-matter is an indication of Dick’s character. (One could never imagine him painting an English pastoral theme.) There are references to the light on the lower deck and its supernatural effect on the painting, on bad drawing, foreshortening and so on.

Examples of colour imagery in the novel are too numerous to individualise in detail, but a selection will make the point. There are references to the grayness of Maisie’s eyes, the magenta of Dick’s necktie (a tiny but notable artistic flourish). Yellow is a colour motif, from the yellow sea-poppy on Southsea beach to Yellow Tina, the Port Said artist’s model, and the recurrent image of the yellow London fog, which some critics have identified as an influence on T S Eliot’s “Preludes” and “The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock”. In addition there are so many striking colour moments’ such as: ‘the crackling volcanoes of many coloured fire’ behind Dick’s increasingly sightless eyes as he paints ‘Melancolia’ in a sleepless delirium. (Ch. XI p. 186)

Colour awareness seems to take on a romantic dimension as Dick and Maisie end a happy reunion day at Southsea. We are almost tempted to believe in the possibility of a happy ending at this point; maybe this is an effect Kipling was trying to create. But at such a moment, when the possibility of romance appears tantalisingly close, there is the subtle hint that Dick is still fixated on the idea of Maisie as pupil-cum-fellow artist:

They…turned to look at the glory of the full tide under the moonlight and the intense black shadows of the furze-bushes. It was an additional joy to Dick that Maisie could see the colour even as he saw it – could see the blue in the white of the mist, the violet that is gray pailings, and all things else as they are – not of one hue but a thousand.(Ch. VII p.113.)

Even as Dick thinks in the language of an artist rather than a lover, we detect both the influence of his father in Kipling’s colour knowledge, and his own writer’s commitment to seeing things as they really are.

Male and female

The gender sub-texts of The Light that Failed are, arguably, the most complex and easily misinterpreted. We have already touched upon the conflict within Kipling/Dick in relation to the two worlds of Art and Action; the latter is inseparable from the novel’s celebration of male camaraderie This is presented most vividly in Chapter VIII, in which Dick’s love for Maisie is set directly against male bonding and the yearning for adventure. The roistering songs serve to emphasise this. “Farewell, to you Spanish Ladies” conjures up the image of the sailor leaving his wife behind, and his desire for the dusky maiden in a distant land. In ‘The Sea is a Wicked Old Woman” the irresistible lure of the sea is the dominant force. The song’s rhythmn becomes, in Dick’s imagination, the pounding of the waves of the Lima cargo boat:

…and the go-fever, which is more real than many doctor’s diseases, waked and raged, urging him who loved Maisie beyond anything in the world to go away and taste the old hot unregenerate life again, to scuffle, swear, gamble … and love light loves with his fellows; to take ship and know the sea once more and beget pictures… (Ch VIII p. 140)

Kipling could not have put it any plainer, although Art does get a brief look-in at the end. The message itself is reinforced by the seductive rythmns of the authors’s prose. This longing, not only for male comradeship, but for a return to the battlefield, is unmistakeably expressed, when the passage above blends into the yearning for:

the crackle of musketry, and see the smoke roll outward … and in that hell every man strictly responsible for his own head, and his alone, and struck with an unfettered arm. (Ch VIII p. 140)

Here is Kipling’s Ideal Man, in action.

The image of the beat of the waves becomes the drum beat and sounds of a guards band playing outside Dick’s rooms, as, tormented by his blindness, he listens, feeling the: ‘massed movement in his face, heard the maddening tramp of feet and the friction of the pouches on the belts.’ (Ch XI p.193) The pathos of this scene is heightened by Kipling’s masterly detail of the sound of the pouches, indicating how Dick’s blindness has sensitised his hearing.

It is here we re-encounter the Negroid-Jewess-Cuban woman ‘with morals to match’ from Chapter VIII. The association of colour with promiscuity could be taken as racist; an accusation that has always tarnished Kipling’s reputation. That is, as he might have said, another story, but the implication in the description lingers. In this context she embodies the erotic and the exotic, and the attraction of forbidden fruit, as Dick enthusiastically recalls: ‘…the sea outside and unlimited lovemaking inside.’ (Ch. VIII p.132) There is almost certainly an element of sexual fantasising in the image of the woman; although implicit, retrospectively for Dick, there is a painful contrast between sexual desire satisfied and love unconsummated.

Because of his blindness, an active sex life is for Dick now an impossibility, and he and the reader realise this. In such a context, his blindness becomes both a disability and a symbol, taking on a sexual dimension. According to Andrew Haggiioannu, in addition to blindness being: ‘a trope for the anxieties of the colonial’s return to London’, it is a Freudian symbol for castration and impotence, ‘which resonates powerfully with the overwhelmingly sexual line upon Dick’s emotional and physical collapse.’ If one accepts this theory, one sees its transmutation into the loss of creativity and helplessness in the face of the power of the female will. (The Man Who Would be Kipling, Andrew Haggiioannu, Palgrave Macmillan 2003 p. 65)

We may widen out the issues of gender and sexuality in the novel by a consideration of the late Victorian fascination for the seductive underground urban worlds of vice and sin, a seediness which assumes a glamour of its own. Gail Ching Liang-Low’s observations on this are particularly illuminating, interpreting the novel as showing: ‘an interesting split between the two sides of Kipling‘s heritage’. She perceives Port Said, Dick’s early hunting ground, as the ‘quintessential Oriental City of vice … sexual perversity’ and ‘dancing hells’ (White skin; Black Mask; Representation and Colonialism, Gail Ching Liang-Low, Routledge Keegan and Paul 1996 page 170). She goes on to describe the voyeuristic fascination for this underworld for artists like Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, linking this with the episode of the Negro-Jewess-Cuban woman. She concludes, therefore, that the novel presents us with, on the one hand a feminine decadent world of sexual pleasure, and on the other the masculine world of adventure, military heroism and male camaraderie. The former is evoked in this lurid description of a ‘mad dance’ which takes place in M and Madame Binat’s house:

…the naked Zanzibari girls danced furiously by the light of kerosene lamps. Binat sat upon a chair and stared with eyes that saw nothing, till the whirl of the dance and the clang of the rattling piano stole into the drink that took the place of blood in his veins, and his face glistened … Dick took him by the chin brutally and turned that face to the light. Madame Binat looked over her shoulder and smiled with many teeth… (Ch III pp. 32-3)

Binat himself warns Dick that he will ‘descend alive into hell as I have descended’, and bemoans his own ‘degradation’ (67).The appearance of this world is relatively brief; in Chapter III and for a short while before Dick’s death in Chapter XV, where a visit to Mme Binat, now a widow, revives memories of the old life. Brief though the scenes are, they are central to our understanding of Kipling’s dual heritage and the novel’s gender oppositions. The decadence of Chapter II is fundamentally no different from that of the seamy side of London’s dark streets, which destroys Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, although Dorian sinks to an unspecified depravity that clearly goes far beyond any of Dick’s experiences. It is interesting to note two opposed concepts of hell emerging; the hell of battle and the hell of moral degradation; two punishments of sorts, ironically linking the novel’s central dualities.

The late Victorian period saw the dissemination of feminist ideas, leading ultimately to the Suffragette Movement, and the concept of the ‘New Woman’ in social, artistic and political life. Readers and theatregoers would know at least something of the ideas of Shaw and Ibsen in this context, whose characters were often the equal of or superior to, their menfolk. Nora Helmer, the heroine of Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House”, which opened in London in 1889, sent shockwaves through audiences, as she rejected her submissive status as her husband’s pretty plaything, leaving him and their children to seek her own indentity and maturity. Ibsen’s blast of cold Scandinavian dramatic air, as Nora walks out of her door, changed theatrical convention for ever. The concept itself, therefore, can be seen as both destructive and liberating.

Many contemporary interpreters of Kipling saw Maisie as an embodiment of the ‘New Woman’, and, consequently, an unsympathetic figure. Hilton Brown, writing in 1945, takes a view which seems a contemporary one for our own day:

Maisie was an unpopular heroine largely because her creator was, for once, years ahead of his time … her views which seemed in those days hard and unreasonable and unwomanly would now arouse no serious criticism. (Rudyard Kipling, Hilton Brown, Hamish Hamilton 1945 p.146)

A notable literary friendship may be significant here. The bond between Kipling and Rider Haggard was characterised by a shared love of adventure and colonial fiction. Kipling would undoubtedly have been familiar with Haggard’s She (1889) which anticipated the gender theories of the Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung. In She Ayesha, a beautiful but powerful and destructive priestess, rises after 2000 years to claim the 19th century explorer-hero Leo Vincey, whom she believes is a reincarnation of her ancient lover Kallikrates. So powerful does she see herself, that at one point she threatens to depose Queen Victoria and take over the British Empire. Her’s is a very different character from that of Ustane, who embodies unselfishness and unconditional love, the very qualities Dick wants from Maisie.

All this is a far cry from the world of art in Victorian London, although the Sudan deserts are a little closer to home. Nor is Maisie an English Ayesha. But this basic principle of role-reversal, and the assumption of opposed gender traits, clearly informs the characterisations of Dick and Maisie, and helps to explain the conflict between them. This being said, all the novel’s textual evidence indicates that Kipling’s treatment of Maisie is more even-handed and credible than those critics who see Kipling as a misogynist would suggest. Kipling’s portrayal avoids the pitfalls which would have romantically conventionalised the relationship. Maisie is enough of a realist to know that there is no chance for them until one or both surrenders to the other, when she says ‘You know I should ruin your life and you’d ruin mine as things are now.’

Maisie is neither femme fatale nor militant feminist, and she is never less than honest with herself about her feelings, admitting to her selfishness in using Dick, and her inability to respond to him sexually. She is not without emotion, however, and her grief at seeing Dick’s blindness is genuine and moving as ‘the fountains of the great deep are broken up’, although she does not normally weep easily (Ch. IX p. 154). Even at the moment of final parting, when Dick cries ‘I’m no good now! I’m down and done for!’ she can never be more than: ‘unfeignedly and immensely sorry for him than she had ever been for anyone in her life, but not sorry enough to deny his words.’ (Ch. XIII p. 219)

It has been said that Maisie lacks sex appeal. She is not, of course, the Negro-Jewess-Cuban woman of Chapter VIII, but the criticism is irrelevant. The whole point is that she does appeal sexually to Dick, whose passion she leaves unassuaged. She is what she is; an independent, ambitious woman and artist, who happens not to be in love with the story’s hero.

Kipling’s view of women

Kipling has been accused of misogyny by some critics, but in the view of this Editor, this is an area where one needs to tread carefully. He is too complex a writer for such a simplification. There is, for example, no trace of misogyny in the characterisation of Helen Turrell in the story “The Gardener” (Debits and Credits 1926), for example, the loving mother seeking her dead son in the war graves of the Great War, nor in the sensitive portrait of the blind woman in “They” (Traffics and Discoveries 1904) It is quite absent from one of Kipling’s most moving stories “Without Benefit of Clergy” (Life’s Handicap 1891) which tells of the passionate, devoted, but short-lived marriage between the Englishman John Holden and his Muslim bride Ameera, which ends tragically with the death of Ameera and her child during a cholera epidemic. There is little doubt as to where Kipling’s sympathies lie in this story, in the tender portrayal of Ameera’s beauty and devotion to her family. There is no trace of misogyny, either, in the character of Grace Ashcroft in ‘The Wish House’ (Debits and Credits 1926), dying of cancer because she has loyally and devotedly, in a mysterious way, taken on the afflictions of Harry Mockler, the man she has loved all her life but who does not return her love. The cumulative evidence of stories such as these may suggest an element of idealisation and wish-fulfilment on Kipling’s part; but this Editor can find no overt trace of misogyny.

The theme of repressed sexuality in The Light That Failed re-emerges in one of Kipling’s most powerful, ambiguous and disturbing stories “Mary Postgate” (A Diversity of Creatures 1917). It is World War I, and Mary Postgate is a lonely, emotionally deprived spinster, who has spent years of her life as a sort of governess to her employer’s nephew Wynn. She cannot even cry when Wynn is killed in a flying accident. Then a bomb falls killing a child, and Mary comes across the wounded German pilot. As she stokes the funeral pyre of Wynn’s belongings, her hatred for the German mounts, whilst she waits for him to die.

an increasing rapture laid hold on her… her long pleasure was broken by a sound that she had waited for in agony several times in her life.

After his death, at the story’s conclusion, Mary contendedly enters the house, takes ‘a luxurious hot bath’ and came down, looking ‘Quite handsome’.

“Mary Postgate” is arguably the most sexually charged story in Kipling’s works; the sense of implied orgasmic release and satisfaction is almost palpable in its intensity at the end of the tale. It is just on the ‘right’ side of explicit, and all the more powerful for being so. Unlike the stories referred to above, there is no demand for sympathy for Mary; not even a judgement as such. Kipling invites an open response by the reader to character and events.

However, many modern critics have undoubtedly found the attitude to women in The Light that Failed unacceptable. As Philip Mallett puts it:

… the novel is punctuated with assertions that women waste men’s time, spoil their work, and demand sympathy when they ought to give it. The only woman it is safe to love is the sea, described as an “unregenerate old hag” who draws men on to ‘scuffle, swear, gamble, and love light loves’… (Rudyard Kipling, a literary life Palgrave Macmillan 2003, p. 57).

It is certainly true to say that the treatment meted out by Dick and to a lesser extent by Torpenhow, to Bessie Broke the artist’s model, who later defaces his picture, is arrogant and chauvinistic, despite Kipling’s pleas in mitigation of Dick’s behaviour, early in the novel, previously discussed. Dick’s reaction to her in Chapter IX is true to his established character and artistic credo, but unpleasant nonetheless, talking about her as if she were an object, rather than a human being:

Do you notice how the skull begins to show through the flesh padding on the face and cheek bone?

This, and Dick’s initial behaviour towards Bessie, suggest an influence on George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (1912), despite Shaw’s dismissal of the novel in a letter to Ellen Terry (Ellen Terry and Bernard Shaw; a Correspondence, Reinhardt & Evans 1949 pp. 337-8). The similarities are quite striking. When Dick attempts to soothe Bessie’s sobbing and wailing with ‘There you are … nobody’s going to hurt you’ (Ch. IX p. 156) it could be Henry Higgins in Shaw’s play talking to Eliza. This impression is strengthened when Dick lays down his employment terms to her:

‘You will come to the room across the landing three times a week at eleven in the morning, and I’ll give you three quid just for sitting still and lying down.’ (Ch. IX p. 158)

The use of ‘quid’ instead of ‘pounds’ emphasises Dick’s contempt for Bessie, and his manner and tone are not totally dissimilar to Higgins’s when he tells Eliza, addressing her as Dick does Bessie, almost as if she were a child:

If you’re good and do whatever you’re told , you shall sleep in a proper bedroom and will have lots to eat and money to buy chocolates … (Act II)

At one point Dick refers to Bessie as a ‘gutter-snippet … and nothing more’, a phrase echoed in Higgins’s denunciation of Eliza as a ‘heartless guttersnipe’. Bessie’s hatred for Dick conveys how difficult and dislikeable he can be, and when she says to him ‘Mr T’s ten times the better man than you are’ she echoes Eliza’s feelings towards Col Pickering, Higgins’s courteous companion. It is also interesting to note that Higgins in Shaw’s play is in the role of teacher, like Dick in the novel, and that both have female pupils who are proving ‘difficult’. Dick’s character however, as this Editor has argued, can in some respects be identified with Kipling’s. Shaw was a more detached and humorous observer, basing Higgins on the distinguished philologist Henry Sweet.

Cruelty in the novel

Two brutal episodes have made some critics very uncomfortable with the novel, but are highly relevant to the theme under discussion. In Chapter III, Dick’s abuse of the Syndicate man, claiming Dick’s work as the Syndicate’s property, despite there being no specific agreement between them (see the Note to page 40 line 28 Chapter III). He even brazenly offers to set up an exhibition of Dick’s work to spread his reputation. This naturally encourages a degree of sympathy with Dick’s righteous indignation. and his angry accusations of theft and burglary are understandable. But he goes further, firstly with threats of physical violence, and then actually manhandling him. It is at this point one detects a distinctly homophobic note intruding:

He put one hand on the man’s face and ran the other down the plump body beneath the coat … ‘The thing’s soft all over- like a woman’ … Dick walked round him, pawing him, as a cat paws a soft hearth rug. Then he traced with his forefingers the leaden pouches underneath the eyes.(pp. 42-3)

Given that Kipling has prepared the way for the negative side of Dick’s character to emerge, there is no mistaking the studied. almost sadistic, and sensual cruelty here; especially in the combination of almost sexual pleasure and revulsion at the man’s body. In Chapter XV, Dick is back in the Sudan, his old battleground, for the last time, and on a train, he hears gunfire, and screaming in the darkness from Arab soldiers. He reacts with unrestrained joy:

‘Dick stretched himself on the floor, wild with delight at the sounds and smells.

‘God is very good–I never thought I’d hear this again. Give ’em hell, men. Oh, give ‘em hell!’ he cried’. (Ch III p. 42-3)

At one level, the episode is a ‘lark’, a boy’s own adventure thrill at his return to the war zone. But at another, in its uncontrolled ecstasy, it suggests an orgiastic, homoerotic response. An interpretation of this kind of thing as symbolic of Dick’s thwarted, frustrated sexuality has not, however, mitigated similar critical disapproval to that of the Syndicate man’s humiliation.

One is very conscious in this particular analytical approach, of over-imposing a 21st century sexual agenda onto late Victorian mores, and reading Kipling too intently in this light. Nevertheless, the text does yield to gender interpretation, but hopefully not at the expense of other important lines of enquiry. The relationship between Dick and Torpenhow has, also, not escaped this particular scrutiny. Torpenhow is counsellor, and honest critic, unafraid to denounce Dick’s arrogance and vanity. His is a fellow press man and war adventurer, drinking partner, and companion about town. In Chapter XI, when Dick, is in an anguish of panic at the onset of his blindness, Torpenhow tries to calm him into sleep, and as he does so ‘kissed him lightly on the forehead, as men do sometimes kiss a wounded comrade in the hour of death to ease his departure’. (Ch. XV p. 229)

This moment consciously anticipates Dick’s death in the Sudan; one can imagine Torpenhow doing exactly the same over his dead body as he cradles him in his arms. In other words, I think Kipling is being truthful and accurate in his interpretation of Torpenhow’s action; it is what one would do to a wounded comrade, and therefore I cannot subscribe to a homoerotic sub-text, nor do I feel the passage stands up to such an analysis.

This is re-inforced retrospectively in Chapter 5, when Torpenhow comes into the studio where Dick is in an emotionally confused state after being with Maisie. He looks at Dick in the darkness:-

… with his eyes full of the austere love that springs up between men who have tugged at the same oars together, and are yoked by custom and use and intimacies of toil. This is a good love, and since it allows, and even encourages, strife, recrimination, and the most brutal sincerity, does not die but increases, and is proof against any absence and evil conduct. (Ch XI p 188-9)

This definition of love is much in the spirit of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 118 (“Love is not love which alters when it alteration finds” etc), and is finely and movingly done; the very essence of their friendship, and indeed the true nature of friendship itself. Nevertheless, whilst there is no sexuality in it, Kipling is certainly describing male friendship, and the unambiguous message here is that Torpenhow is providing more durable and meaningful support than any woman can.

War and Pessimism

The novel’s maleness is inseparable from the idea of War as adventure. As Eric Solomon puts it: ‘Kipling sought to use the idea of war to represent metaphorically a way of life – in this case the life of vigorous action, from which the artist-hero strays’. [English Literature in Transition: 1880-1920, Eric Solomon]. But we should also remember the impact on England, at the time, of an actual war and its aftermath, and the fate of a real-life great Victorian hero figure.

There can be few readers who are unfamiliar, at least in outline from history or the cinema, of the dramatic conflict between General Charles George Gordon and his enemy the Sudanese rebel leader the Mahdi; a conflict which symbolises Empire and visions of Empire even now, and still captures the popular imagination. The 1884-5 Expedition to the Sudan under General Wolseley, to relieve the besieged Gordon at Khartoum, pre-dated the novel by some 5 years. The Sudan campaign, as Imperial and military history was clearly in the forefront of Kipling’s mind during the gestation of “The Light That Failed”. [The historical background is covered in the detailed Notes for Chapter II and for Chapters XIV and XV, and in the account given in an Appendix to ORG. The context of these events has sometimes been mistaken for the Battle of Omdurman, which heralded the final defeat of the Mahdi, but that was not until 1889, well after the novel was written.]

The Anglo-Indian community reacted with enormous shock to the news of Gordon’s fate, and we may be pretty sure that Kipling reacted in the same way, given his likely admiration for Gordon as a man of action and a hero of the Empire. Public opinion in Britain blamed the Government, particularly Gladstone, for failing to relieve the siege. Some historians, however, have accused Gordon of defying orders, and refusing to evacuate Khartoum despite the late possibility of doing so.

These events, described in Chapter II of The Light that Failed, and their background influence the whole novel, up to and including the final two chapters. Gordon himself has only a few brief mentions, but he seems to cast his unacknowledged shadow over the novel’s action.

The most striking fact about the war sequences is that Kipling had never been on a battlefield, let alone in the Sudan campaign. It was the Boer War that later gave him his first experience of the real thing. He had only visited Egypt for 4 days in Port Said aged 16, during an earlier Egyptian war. So the vivid and realistic descriptions that Orwell and other critics have so admired, were derived from Kipling’s own imagination enhanced by reading numerous eye-witness acounts of the conflict. It is not only the descriptions of action and scene that impress, but the attention Kipling gives to the details of military resourcing, tactics and logistics. (He was later to apply the same approach to the Jungle Books (1894), evoking a jungle world from images and books about a part of India he had never visited.)

If the tragedy of Gordon seems to anticipate the end of Empire, the sombre mood in Britain which followed it can be seen as related to the mood of world-weariness and pessimism which characterised the late 19th Century; ironically co-incidental with the high tide of Britain’s wealth and imperial supremacy. William Knighton summed up the atmosphere in his 1881 essay on suicide for the Contemporary Review (no 39, 1881): ‘Men everywhere are becoming more weary of the burden of life’. And Knighton describes ‘the erosion of vitality’ brought about by ‘the force of their own inventions, runaway science, runaway technology, runaway urbanism.’

Such a view of life can be traced back to Wordsworth and his withdrawal from revolutionised society, and is discernable through the work of of Tennyson, especially in “In Memoriam” (1853), to the French Symbolists Rimbaud and Baudelaire, to Poe, Wilde and Hardy’s tragic fatalism. Wilde expressed the sense of a world suddenly become meaningless and out of joint, in the macabre musical imagery of “The Harlot’s House”:

Then suddenly the tune went false

The dancers wearied of the waltz

The shadows ceased to wheel and whirl

(“The Harlot’s House” Oscar Wilde (1885) Complete Works, Collins page 790)

An earlier example, Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach” (1865) one of the great lyric poems of the 19th C, contemplates the Age’s crisis of religious faith, and the need for love and stability in a world without order. The poem ends with his vision of a society that:

Hath neither joy, nor love, nor light

Nor certitude nor peace nor help for pain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and fight

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

(“Dover Beach” by Matthew Arnold: Palgrave’s Golden Treasury 1980 ed. page 790)

The power of the poem derives from a profound moral awareness of a kind of heart of darkness. There is an interesting and instructive parallel between this late Victorian sense of alienation, and the mood of the 1920’s; similarly an age of great prosperity and endless possibilities. Yet, it was the darker moral and spiritual underside of that society which concerned writers like Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald and D H Lawrence. And darkness and alienation certainly pervade the final chapters of The Light That Failed, indeed our own age is comparable, which is why this Editor finds in the novel a modernity as well as a portrait of its time.

The 1870’s and 1880’s also saw a liberalising of the attitude towards, and philosophical concern with the idea of suicide, as Knighton’s article suggests. In The Light That Failed when Dick is most painfully aware of the hopelessness of his condition, he is kept alive by:

‘a lingering sense of humour … suicide he had persuaded himself would be a ludicrous insult to the gravity of the situation, as well as a weak-kneed confession of fear.’ (Ch. XIV p. 235)

This is clearly Dick the brave, but the passage indicates that suicide has crossed his mind, and that he is no stranger to fear. It is possible, in the light of this, to see his death as both an act of heroism and of willed suicide, a euthanasia of a kind, aided by Torpenhow, whom he has asked to deliberately put him to ‘the forefront of the battle’. In the view of this Editor the novel’s penultimate paragraph could justifiably support this interpretation:

His luck held to the last, even to the crowning mercy of a kindly bullet to his head.

(Chapter XV p. 289)

Cities of Dreadful Night

There are two works entitled “The City of Dreadful Night” which are important influences on The Light That Failed. One is the collection of eight articles by Kipling describing Calcutta, originally published in the Civil and Military Gazette and the Pioneer in 1887-8, and later as sections of Letters of Travel, in Volume 2 of From Sea to Sea in 1900.

There is also the surreal narrative poem by the Glasgow-born poet James Thomson, from whom Kipling borrowed the phrase. This appeared in instalments in the National Reformer in 1874, and in book form in 1880.