Introduction

It should be made clear at the outset that this article is intended only to examine those stories and other writings of RK which relate to the Royal Navy, or Royal Naval men. It will not examine his naval verse, other than where the verses are normally to be found as headings to a story: nor will it touch on his other sea stories, such as “The Ship that found Herself” and “Bread upon the Waters”.

In essence, Kipling wrote eleven stories which featured naval personnel, of which six were written around Petty Officer Pyecroft. They comprise (the dates of first publication refer to publication in Great Britain – most American dates were nearly simultaneous, or even slightly earlier)

Kipling also published one other piece of what may loosely be called naval fiction. In A Book of Words (Macmillan, 1928), a selection of his speeches and addresses, will be found “The First Sailor”. Since the setting of that particular piece predated the King’s Ships, let alone a more formal Royal Navy, by several millennia, it is probably stretching it to include it under the heading of ‘Kipling and the Royal Navy’. But its original audience in 1918 were young Royal Navy officers, and its whole ethos was based on the Royal Navy.

He also wrote a one-act play act “The Harbour Watch” which featured Petty Officer Pyecroft, and which was performed in London at the Royalty theatre in 1913.

Kipling also published two books of articles on the Royal Navy:

A Fleet in Being, (Macmillan, 1898), and Sea Warfare, (Macmillan, 1916), which contained The Fringes of the Fleet, which had been published separately (December 1915).

And he also delivered a short address on “The Spirit of the Navy” at a Naval Club in 1908, which is collected in A Book of Words.

The above comprise the oeuvre on which this article is based. It may surprise some readers to see “Mrs. Bathurst” included in the list. It is true that it is scarcely a story about the Navy, but the story teller and a number of the characters, which include Pyecroft, are naval, as is the background. It is not intended to dissect what is generally accepted as being one of Kipling’s more dense, even impenetrable, tales, but to treat it on a superficial level, as a naval story, leaving the deeper levels to be tackled elsewhere.

The factual basis

Kipling’s first acquaintance with the Royal Navy would seem to have been as a child in 1872-4, during the six year period when he was living in the “House of Desolation” with the Holloways, in Southsea, Hampshire.

Southsea is one of the towns and villages which stand on the island of Portsea, which is enclosed, with other islands, in an area of water on the north side, and at the eastern end, of the Solent, that stretch of water between the Isle of Wight and the mainland of England. In the 1870s, Southsea was more-or-less isolated by a green belt from its western neighbouring town, Portsmouth, whose 17th century fortifications were still largely intact. Portsmouth was then, as indeed it remains, Great Britain’s premier naval port, and could, and can, fairly be described as the home of the Royal Navy.

Kipling and his sister had been left by his parents with Captain and Mrs. Holloway at Lorne Lodge, 4, Campbell Road, Southsea, in a manner which was not unusual in those days for the children of Britons working overseas. There are descriptions of this period of his life in Something of Myself, and, in fictional form, in “Baa, Baa, Black Sheep” (Wee Willie Winkie 1888), and The Light that Failed (Macmillan 1891).

The Young Boy and the Old Sailor

Captain Holloway had served as a young man in the Royal Navy, and had been present as a Midshipman at the battle of Navarino in 1827, at which he was wounded. The wound prevented his continuing a naval career (and in any case, the Royal Navy of the 1820s and 30s had many more qualified officers than it could employ), so like many others, he had to find other employment.

Andrew Lycett (pp.34-5) gives a concise description of Captain Holloway’s career, and of how he would take the seven year old Rudyard with him when he walked to the Dockyard to collect his Coastguard pension from the Cashier’s office. (Captain Holloway had spent the last eleven years of his active life in the Coast Guard, then administered by the Royal Navy, although its personnel were a mixture of former merchant and Royal Naval men.) The walk, about a mile-and-three-quarters there, and another mile-and-three-quarters back would have been quite a walk for a young six-to-seven-year-old.

However, an article by Mike Kipling in KJ 367 (Mar. 2017) suggests that Captain Holloway’s rank derived, not from any sea service, but from his holding a Captain’s commission in the Oxfordshire militia. The article also casts doubts on the precise nature of Captain Holloway’s presumed voyage(s) in a whaling ship. We believe that he may indeed have had such service, but not as Master of such a vessel, which might have entitled him to style himself ‘Captain’.

Both Carrington and Lycett contain minor errors of Royal Naval detail. Captain Holloway was never Captain H. Holloway, RN (Carrington, endnote 4 to Chapter II). He never held a commission in the Royal Navy, and as has been explained above, his title of Captain might have derived from his service in the merchant marine, as well his militia commission. And Lycett claims that Kipling, in Something of Myself, must be mistaken when he writes of “the timber for a Navy that was only experimenting with iron-clads such as the Inflexible lay in great booms in the harbour”, because, Sir John Keegan has written, “after 1865, all the Royal Navy’s new ships were built of iron…”

Unfortunately, Sir John is only partially correct. From 1865 onwards all battleships were, indeed, made of iron, but they utilized a great deal of timber in their construction, not merely for decks and partitions and their multitude of boats, but for their armour which was a sandwich of iron on the outside and inside, with teak in between. And the small sloops and gunboats (cf the Redbreast mentioned in the notes on “Judson and the Empire” which follow) were of composite construction, that is to say, they had an iron frame, but were planked with wood, in the same fashion as the Cutty Sark, which may be seen at Greenwich, or HMS Gannet, in Chatham Historic Dockyard. Such ships were being built for the Royal Navy up to 1890.

But Kipling is perhaps being unintentionally misleading when he speaks of the Navy “only (my emphasis) experimenting ….” and of HMS Inflexible, though he might well have known of the latter. It can fairly be said that the Navy was experimenting with iron ships in the period 1860 to 1885, but it was with the form, rather than the material – the period of experiments with iron as a material had, in broad terms, been from 1840 to 1860. Although iron had many advantages over wood as a shipbuilding material, there were other disadvantages (one being the fact that it was not until the 1850s that a reasonably reliable means of correcting a magnetic compass for use in an iron ship was found – again, see the notes on “Judson and the Empire”).

As for the Inflexible, she was laid down in February 1874, and Captain Holloway died in December that year. Kipling might have been taken to see her on the slips (she was built in Portsmouth Dockyard), and he would almost certainly have heard her spoken of by the Captain and his friends, because she was a topic for discussion right from her conception. It is doubtful if he ever saw her completed, when for a short period she was the acme of British sea-power. However all that may be, Kipling’s recollection of the timber in the harbour and its purpose was undoubtedly correct. Andrew Lycett also says “Rudyard’s recollections have several inaccuracies. For example, he claimed he and the Captain saw the Arctic exploration vessels HMS Alert and HMS Discovery in Portsmouth harbour after their historic polar expedition”.

In fact, Something of Myself only claims to have seen one or other of the ships, but as Lycett correctly says, they didn’t return until autumn 1876, nearly two years after Captain Holloway had died. There are two possibilities. One is that he did see one or other of the ships after their return, but not in the Captain’s company. This might be possible. None of the biographies suggest that Mrs. Holloway kept him confined the whole time. It depends how much freedom to wander in Portsmouth and Southsea he had. It would seem from his own account that he had considerable freedom to do so. In a letter dated 22 October 1919 to André Chevrillon ( The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Volume 4, Ed. Pinney) he says, a propos of Captain Holloway:

…with whom as a small boy I perambulated all Portsmouth, Gosport and Fratton – the old Portsmouth with its ramparts and old houses. He died but the town remained to me and as I grew bigger I wandered all over it and the mudflats at the back among the old forts”.

Alternatively he may have seen one or other, in the Captain’s company (or possibly on his own), shortly before the old man died, while they were being prepared for their voyage. The Navy Lists show that Alert was in Devonport (Navy List (NL) for 20 Sept. `74), and arrived in Portsmouth sometime between then and 20 December `74 (NL for that date has her marked as ‘Portsmouth’): while Discovery was purchased to act as a storeship for the proposed expedition on 5 December `74. So, in the absence of other information (such as Alert‘s log, to tell us the exact date she arrived in Portsmouth), one can say that it is possible that Kipling (whether in company with the Captain or on his own) saw Alert any time from the beginning of October `74, and Discovery any time from mid-December `74.

On the whole, though, it would seem more likely that he saw the ships on their return. The author of this note is now almost the age that Kipling was when he started to write Something of Myself, and would say that one doesn’t mis-remember events, but the timing of them can often be uncertain – and there was no need, in Something of Myself, to invent something that didn’t happen, and to embellish it with the detail about timber from the rudder. But, if one accepts that Rudyard had an enquiring mind (using, if nothing else, the description in Stalky and Co. of Beetle questioning the “workmen as they moved about a half-finished cottage” in “An Unsavoury Interlude”), then the whole description rings true. And given that Captain Holloway had been in the Arctic himself, unless he had spent his last months housebound, it would seem quite possible that he would have taken young Rudyard to see the Arctic ship, or ships.

All this means that by the time he left Southsea, the young Kipling must have known more than most of his contemporaries about the workings of the Royal Navy, as seen through an old sailor’s eyes: this at a time when things naval were starting to penetrate the national consciousness, and were the subject of frequent discussion in newspapers, whereas half a century earlier, they were of concern only to the seafaring population, and the better educated who might have read the novels of Captain Marryat.

Schooldays

When he went to school, he would have lost contact with the Royal Navy. The United Services College was, if it was anything, an ‘army’ school: and in any case, boys destined for a naval career, whether as an officer or on the lower deck, went to join one of the training ships at the age of twelve to fifteen, so it is unlikely that any potential naval officer would ever have been educated at the USC, other than briefly, in Kipling’s time. But he might have had fleeting contact with a fringe of the Royal Navy: this is suggested by the implication that he had access to the Coastguard cottages (“An Unsavoury Interlude” again), and that Richards, house-servant to Prout (in reality, M.H. Pugh), was an ex-navy carpenter. (This last, incidentally, is another example of the Navy’s specialist use of words to mean something different to the general public than to the Navy man. An ex-navy carpenter (lower case ‘c’) is, in this case, a wood-worker who has served in the Royal Navy. To someone in the Navy, a Carpenter (capital ‘C’) is a Warrant Officer, and a man of considerable experience and skill and standing. An ordinary wood-worker would be a Carpenter’s Mate.)

The Young Author

His first real contact with the Royal Navy would seem to have been in 1891, on his first voyage to South Africa. His meeting and friendship with Commander, later Captain, E.H. Bayly, Royal Navy is recorded in Something of Myself, and amplified in Carrington and other biographies. (Though it must be recorded that, despite writing in Something of Myself that their initial meeting “laid the foundations of a life-long friendship” (p.95), he referred to him by name (p.148) as Captain Bagley.) It can fairly be said that “Judson and the Empire” was one result of that friendship, and the Harbord notes to that story contain greater detail about their first meeting:

[The author of these notes has recently (March 2006) come across some reminiscences about Captain Bayly which are interesting in themselves, and perhaps explain whence Kipling derived his particular view of the Royal Navy, and incidentally, explain the reference to ‘Captain Bagley’.

In An Admiral Never Forgets, by Captain, later Vice-Admiral, H.H. Smith, he records that:

“the captain of the Pelorus, one Chawbags Bayly, came on board to call on our new captain … Chawbags Bayly was a hearty, burly, thoroughbred seaman of the old school, with square-faced whiskers, a fore-royal yard voice, and a vocabulary fully charged with poetical similes.”

It would seem possible that Kipling was aware of the nickname, and when writing Something of Myself late in life, confused the nickname with the real name. Captain Bayly also had a reputation for “making the punishment fit the crime”, and that, too, may possibly have conveyed an idea for “The Bonds of Discipline”.]

In the five years that followed, he had little to do with the Royal Navy (though Angus Wilson (The Strange Ride of Rudyard Kipling, Secker and Warburg 1977 [0-435-57516-7]; Viking Penguin 1978 [0-670-67701-9], paper 1979 [0-14-005122-8]) quotes Admiral Evans, of the USN, saying that Kipling had taken an interest in the ships of the USN during his various visits to New York), but on his return to England at the end of 1896, and while he was living in Torquay, he visited the training ship HMS Britannia, as is recorded in Birkenhead’s biography (Birkenhead, Lord Rudyard Kipling Hutchinson 1978; Random House 1978 [0-394-50315-5 0]). And next year, shortly after leaving Torquay, he was invited by Hamo Thornycroft, the sculptor, to attend the sea-trials of one of his brother’s new destroyers (Birkenhead, chapter XII). The description of his experiences later provided material for part of “Their Lawful Occasions”. Later that year, his old friend Captain Bayly (he had been promoted on 01 January 1894 at the end of his time in command of the Mohawk) invited him to be his guest on board the Pelorus, to which Bayly had been appointed in command on 30 March 1897.

To Sea with the Navy for the First Time

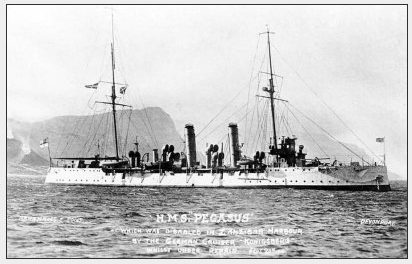

He spent about a fortnight on board the Pelorus (illustrated at the head of this article), taking part in the annual manoeuvres from mid-June 1897 to early July, and since this period and a similar trip in the same ship the next year provided most of the background material for all the Pyecroft stories, it may be worth-while to describe her.

She was one of a class of eleven ships, and the name ship of the class, although not the first to be completed. She had been built at Sheerness Dockyard, completed in December 1896, and first commissioned at Chatham on 30 March 1897. So Captain Bayly was her first captain, and she was manned from the Chatham Port Division, which means that the crew would have been drawn from the east of England, with a strong contingent of Londoners. She was officially described as a twin screw cruiser, 3rd. class, and was an elegant looking little ship, of only 2135 tons displacement, 300 feet long, and only 36½ feet in beam. She had two raked funnels, and two equally-sized masts and would have been painted black, with white upper-works and buff funnels. Her armament was pretty slight, eight 4-inch guns and 8 3-pdrs, with 3 machine guns, and two above-water torpedo tubes for 18 inch torpedoes.

In a letter to Doctor Conland, quoted in Carrington, Kipling refers to her as a “new 20-knot cruiser”, as though that were something out of the ordinary, but her speed advantage over the battleships for which she was supposed to scout would not have been very great – the battleships of the Channel Squadron, to which Pelorus was attached, had a top speed of 17 or 18 knots, which speed (all other things being equal) they could maintain in weather conditions which would make the poor little Pelorus run for shelter. Her machinery (and undoubtedly Kipling visited her boiler-rooms and engine room) consisted of two sets of triple-expansion steam engines, capable of developing 5000 indicated horse-power with the boiler operating with natural draught, and 7000 horse-power with forced draught. To obtain her ‘high’ speed, she was made long in relation to her beam, with the result that she was a poor seaboat, having a heavy roll, and tending to be wet in heavy weather. Pelorus and the other ships of her class were also used as guinea-pigs, in that they were fitted with a variety of boilers to test the qualities of some of the many water-tube types available: Pelorus herself was fitted with Normand boilers, a type which did not ultimately find favour.

But no doubt she was the apple of Captain Bayly’s eye, the more so, since his appointment to her meant that he was back on full-pay. (In those days, it was the practice that, on promotion, you were removed from your present appointment, and put on half-pay until an appropriate appointment in your higher rank was available. This meant that, in financial terms, promotion was something of a mixed blessing: though in an era when most naval officers had some form of private income, it had less effect than it would if it applied today.) She was part of the Channel Squadron, in fact she was the junior ship of all (that is, her captain’s seniority was later than all other officers in the squadron – she would be referred to as the ‘canteen boat’ in later parlance), under the command of Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Stephenson, KCB.

The squadron consisted of eight battleships (of two similar classes), and six cruisers of differing types and capabilities, of which Pelorus was the smallest. It is probably fair to say that it ranked second in importance and prestige to the Mediterranean Fleet of the period. In fact, it seems likely that when he wrote “The Bonds of Discipline”, Kipling had Pelorus in mind in describing the imaginary Archimandrite.

A Second Trip in the Pelorus

He had a second trip in Pelorus a year later (1898), from Devonport to Bantry Bay and back to Portland, again as a guest of Captain Bayly. It may be noted that Birkenhead’s biography contains some errors (pp191-2). Birkenhead speaks of him being “the guest of Captain Norbury”, but Captain Bayly was still in command, and it was as his guest that RK spent a fortnight in the ship. Norbury was Lieutenant Norbury, the junior watchkeeping lieutenant on board (Navy List, September 1898). So the “amusing and ingenious tour de force” quoted in Birkenhead, p. 192, as being addressed to Captain Norbury must have been so addressed in fun. Birkenhead says that it “introduces the name of every ship in the squadron”. This is not actually the case: there are twenty ships’ names, of which seven only belong to Pelorus‘s squadron (and there are seven other ships in that squadron whose names do not feature). The remaining thirteen names are drawn from other fleets and squadrons, some of which (those currently on the China and North American stations) were certainly not in home waters at the time. In fact, from a look at the “List of HM Ships in commission for 1897 and 1898”, ( a monthly official publication, giving the station and details of all ships in HM’s Navy in commission), it seems more likely that the jeu d’esprit was written in the previous year 1897. All of which is petty stuff, but, as ever, pointless errors in a work lead one to ask what other ones there may be. Birkenhead also says “The ship’s company, from the Commander down to the ratings …..”: in this case, this is a misuse of the word Commander. Pelorus‘s captain was, as we have seen a Captain in rank, and would have been referred to as such. His second-in-command in a small cruiser like Pelorus was a senior Lieutenant, not a Commander by rank, and was referred to as the First Lieutenant.

A Third Trip with the Royal Navy

In the summer of 1901, Kipling made a third short voyage with the Royal Navy, which appears to be less well documented. This Editor’s attention was caught by an illustration on the dust jacket of Meryl Macdonald’s The Long Trail, which shows Kipling sitting cross-legged on the deck of a ship: the caption states that it was taken on board HMS Nile during the annual manoeuvres of 1901.

This is amplified by entries from Carrie Kipling’s diaries, as recorded in Birkenhead. Carrie was undergoing a severe fit of depression while Kipling was away, first visiting his parents, and then going on to take what seems to have been a very short trip up the south coast in the Nile.

20. [July] Still down. Rud joins his ship and gets into her this evening.

21. Still more down in body my mind doing a series of acts in a circus beyond words to depict in its horrors. Rud writes from Sandown Bay at Anchor.

22nd. Dreary enough. Rud at anchor off Brighton.

26. Rud at Shillington. [Shillington is a village in Bedfordshire, four miles north-west of Hitchin.]

From the above it would appear that he spent no more than six days in the Nile. But Carrie’s diary entries are amplified by letters which Kipling wrote

(The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Volume 3, Ed. Pinney). He wrote first to his mother-in-law on 5 July, 1901 as follows:

I go away first to Tisbury to see my people and then with the fleet on its manoeuvres about the 12th or 13th. I shall be away for a fortnight or three weeks at least….

He also wrote to Moberly Bell (Editor of The Times) on 14 July, including the phrase: ‘…I go down to Weymouth tomorrow to join the Nile,.’ And when it was all over, he wrote to H.A. Gwynne (journalist, later Editor of the Morning Post) on 23-24 August 1901:

Did I tell you how I was out from the 20th to the 31st of July with the fleet on Manoeuvres? I had the ill luck to be on the beaten side – and battleships at that. Our admiral “didn’t believe in destroyers” – i.e. the light horse. Result was he was out-scouted outwalked out manoeuvred and generally De Wetted all up and down the Channel. The navy is pretty good but its still full of spit and polish and fuss and muckings.

The admiral referred to was Sir Gerard Noel: and the expression ‘De Wetted’ refers to the Boer General De Wet who successfully surprised British troops on several occasions, as Admiral Noel evidently was on this occasion. (But he had a reasonable excuse – his fleet was definitely ‘the ‘B’ team’, and his opponent was Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson, VC, who was generally held to be an excellent tactician.) And the Nile, although only ten years old and with a successful commission in the Mediterranean behind her, had already been relegated to being the port guard ship in Devonport. It would appear that Kipling had become acquainted with Nile’s second-in-command Commamder Henry Clarke, through the latter’s wife, who was a neighbour of the Kiplings in Rottingdean. (Thomas Pinney (Ed.) Letters lII, footnote to letter dated 27 June 1907.)

The fact that he joined Nile at Weymouth was used as material for “Their Lawful Occasions”, in which Nile becomes the Pedantic.

The Fruits of his Naval Experience

Some two years elapsed between his trip in the Nile and the appearance of the first Pyecroft stories. Of the first five stories, all originally published in 1903-4, only two are really about the Navy – the other three involve naval personnel, and are larded with navalese, but are set on shore. Kipling’s biographers have mostly written these stories off as being less than Kipling’s best, if not second rate. David Gilmour (The Long Recessional, John Murray, 2002) repeats the good point that, by the time he came to make the acquaintance of the Royal Navy, he was an established figure:

Fame had blocked Kipling’s descent to the lower decks. He wrote great verses about the sea, but he never wrote a good story about the Navy.

The author of this essay would beg to disagree: there are only six stories which can really be said to be about the Navy: “Judson and the Empire”, “The Bonds of Discipline”, “Their Lawful Occasions”, “Sea Constables”, “A Flight of Fact” and “A Sea Dog”. All are technically correct (as near as a non-naval writer can ever get) and are typical examples of Kipling showing off his virtuosity in a different field. “Judson”, and “A Flight of Fact” are comedy, while “The Bonds of Discipline” is pure farce. “A Sea Dog” has more to it than appears from its lumping together with Kipling’s other dog stories.

But it is suggested that both “Their Lawful Occasions” and “Sea Constables” are distinctly good stories, judged on literary merit, although some dislike “Sea Constables” as being one of Kipling’s ‘hate’ pieces. Which it may be, but it is nonetheless a good story, reflecting the time it was written (in 1915). What is lacking in Kipling’s naval stories is any inkling of sailors’ lives beyond their ship. In “Bread upon the Waters” (the merchant marine), we get at least a glimpse of Mrs. McPhee, and the McPhee home: there’s never a hint of a Mrs. Pyecroft. One point to be made about the critics’ opinions is that, so far as this writer is aware, Kipling’s naval readers, then and now and in between, all thought that the tales were good. They didn’t think that he was just showing off, but that he had lower-deck speech right (within the constraints of what was publicly acceptable in those days – but I dare say the Soldiers Three used words which would have had Victorian ladies covering their ears), and the camaderie on board. Similarly, Army officers applauded Kipling’s stories of soldiers. There is at least a case for suggesting that the critics, out of incomprehension, couldn’t understand his naval stories.

Kipling and the Navy at War

As part of his pre-occupation with the state of the Empire’s defences, Kipling continued to take an interest in the Royal Navy, moving to a rather higher plane than the barrack-room and lower deck, even above the officers’ mess and wardroom. He became acquainted with Admiral Sir John Fisher when he was C-in-C Portsmouth, who invited him to visit a submarine (though on this occasion it would seem to have been only in harbour: had he been to sea, it must have resulted in some writing: in 1915, he did go briefly to sea in a submarine – see The Fringes of the Fleet). And he had hopes of his son John joining the Navy, for which Fisher offered to procure him a nomination. Later, when Fisher was First Sea Lord, although he was preparing the Royal Navy for the war with Germany which both men saw as inevitable, Kipling fell out with him, writing of him in terms as extravagant as the ones which Fisher himself used. Considering the views about Germany which Kipling held, this is hard to understand, but Kipling disapproved of the measures which Fisher was taking in relation to the disposition of ships in the rest of the Empire, and had become a supporter of Admiral Lord Charles Beresford, who at this time (1908-10) was carrying on what can only be described as a most improper feud with the First Sea Lord, to the great detriment of the Royal Navy.

Although poor eyesight meant that his son John was now intended for an Army career, Kipling still had time to visit the Navy. Immediately before the outbreak of war, he attended the Naval Review at Portsmouth, seeing it from the pre-Dreadnought battleship, HMS Exmouth. But his first direct contact with the fighting, or with the fighting men on the battlefield, was not until the summer of 1915. After a visit to France in August, he undertook what was a straight piece of journalism (Carrington says “strong pressure was brought on Rudyard by the Admiralty”).

The Old Reader’s Guide (ORG) and “Kipling’s World War 1 Writings on the Navy”.

ORG describes its genesis in the following terms:

“It is recorded that early in the First World War, General Foch, later to be Allied Generalissimo in France, did not consider that the British Fleet was worth a bayonet to the Triple Entente. Sir Henry Wilson, a future Chief of the Imperial General Staff, thought perhaps 500 bayonets was nearer the mark. Most of the British public – either instinctively or through reading Captain Mahan’s works” (Captain A.T. Mahan, USN, (1840-1914), the most influential writer on naval matters of the period) “- knew better than these military experts, but rigid censorship and a comparative scarcity of dramatic events in home waters had left most of the work of the Royal Navy shrouded in northern mists. More information was needed, in the interests of all concerned. Kipling had declined invitations from the Government to write other official propaganda of a general nature, but an urgent request from the Admiralty to describe naval operations, particularly those of the smaller ships, was nearer his heart.”

“He spent most of the autumn of 1915 visiting the headquarters of the east coast patrols, Dover and Harwich. On his return from one visit, he learned that his son in the Irish Guards was wounded and missing in the Battle of Loos, but he resolutely completed The Fringes of the Fleet. The following year he again went to Dover and the submarines at Harwich (with whom, and their depot ship, HMS Maidstone, he had established a close link), and he also visited the Grand Fleet in the north, but he evidently found few witnesses of much assistance except for background knowledge, largely through their inability to see anything noteworthy or remarkable in their own work. “Tales of the Trade” and “Destroyers at Jutland” are therefore based mainly upon the official reports of the submarine and destroyer officers concerned.”

“In the circumstances, it is not surprising that although Sea Warfare rises well above most of the contemporary commissioned publicity, it lacks something of the spontaneity and colour of A Fleet in Being, which was written from first-hand impressions in an earlier and happier period.”

“It may also be pointed out to any readers inclined to question the substance and taste of some of Kipling’s comments on our enemies that Germany’s conduct of the war from the Invasion of Belgium in 1914 to the Armistice of November 1918, showed a disregard for international law and usage, her own treaty obligations, the position of non-combatants and for common decency that had not been known in Europe for hundreds of years. Her official policy of ruthlessness was often carried to revolting extremes by individuals – for example, the U-boat captain who, having inexcusably torpedoed the hospital ship Llandovery Castle, attempted to destroy the evidence by machine-gunning the survivors in the boats, The cartoons by the Dutch artist Raemakers vividly illustrate the effect of such behaviour on independent neutral opinion, In the end, ruthlessness ensured Germany’s defeat by bringing the United States into the war against her – a calculated risk, deliberately accepted – but it came near enough to success to encourage Hitler to believe, twenty-five years later, that it needed only to be resumed more methodically and drastically.”

“(In fairness to Hitler’s Navy, we may note that although in 1939 U-boat warfare against merchant shipping was a gross national violation not only of international law, but also of an agreement accepted by Germany between the Wars, exercises in personal sadism like the Llandovery Castle affair were almost unknown in the Kriegsmarine in 1939-45. We should not care to make the same claim for the Luftwaffe.)”

Most of the naval content of ORG was contributed by Rear-Admiral P.W. Brock, CB, DSO,*, who died in 1988. In the various notes which follow, covering the naval stories and other writings, direct quotes from ORG are indicated as such (e.g., the five paragraphs above). Otherwise, and particularly in the textual explanations, the ORG comments have been woven into the later amplifications, for which the contributor of these notes is happy to accept responsibility.

Angus Wilson has a few brief words about this period, also making the point that Kipling didn’t get to talk to the lower deck during his time with the fleet. (Wilson refers to “Admiral Bullard” as being Kipling’s host – he was in fact Rear-Admiral, later Vice-Admiral Ballard, whose writings on the late Victorian navy are among the best there are, both in detail and atmosphere.)

Sea Warfare is not without interest, but it does not add very much to the understanding of the First World War at sea. As the great majority of our readers will know, there was only one major encounter between the fleets, off Jutland on 31 May 1916. The result is best described by an American journalist who wrote, “the German fleet has assaulted its British jailer, but remains in prison.” Kipling’s description, in “Destroyers at Jutland”, of the night encounters which followed the main fleet actions is, to this reader’s eyes, confused, and difficult to follow. In this, it is possible that Kipling was reporting better than he knew, since undoubtedly the actions were confused, with neither side being aware of what the rest of its own side was doing, let alone knowing what to expect of the enemy. And even if Jellicoe and his staff had made their intentions and assessment of the enemy’s movements crystal clear to their own side, carrying out those intentions was, to say the least, going to be problematic in the days before radar and any form of radio navigation; with a magnetic compass which might be accurate to within a degree; after twisting and turning all afternoon, with speed varying frequently, so that one’s dead reckoning could be little more than a matter of inspired guesswork. It is, perhaps, instructive that when the definitive report of the battle came to be written after the war, the plotting of the whereabouts of all the ships was based on the one fixed point which every ship marked on its plot, the place where HMS Invincible sank, her bows sticking up out of the water like a beacon, so shallow are the waters of the North Sea.

Post-War Years

There was only one story concerning the Navy in the years immediately following the war, “A Flight of Fact” which first appeared in 1918. It was well suited to the whole tone of Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides in which it was collected. His final pieces of naval fiction were “A Naval Mutiny” written during his enforced stay in Bermuda, while his wife was ill, in 1930, and “A Sea Dog”. The former is, in the writer’s view, a very slight piece, but “A Sea Dog”, if you disentangle the sentimental story from the meat, is a description of wartime derring-do in the North Sea, which is, navally, not unlike “Their Lawful Occasions” being played out in real life.

Kipling maintained an interest in the Navy (and the armed forces in general) as part of his concern over the rise of Nazi Germany, being particularly worried about the effects of the Treaty of London in 1930. This treaty, the second of the two major armaments treaties between the Wars, placed further limitations on Great Britain, and allowed further concessions to the Germans. His final visit to the Navy occurred in the year before his death, when he attended King George V’s Jubilee Review at Spithead.

The Critics and Kipling’s Naval Stories

As was said above, most critics have been less than enthusiastic about Kipling’s naval writings, but it is probably fair to say that they were always popular, over a period of thirty years and more, with naval personnel. In the introductory notes to the Pyecroft stories in the Original Harbord, Admiral Brock quoted Captain Peter Bethell, Royal Navy, who wrote:

“In my view they” (the Pyecroft stories) “are easily the best stories woven round the Navy that have ever been written: and while I am airing my views I may as well add that I make Colonel Drury a good second, C.S. Forester third, and Captain Marryat fourth – ‘Taffrail’ and ‘Bartimeus’ also ran. The remarkable feature of the Pyecroft series has always seemed to me to be the absolute verisimilitude of the conversation, whose tiniest details are quite impeccable. Kipling’s consciousness of this is engagingly shown by a remark he puts into the mouth of Pyecroft who says on one occasion, referring to Kipling, ‘I know he’s littery by the way he tries to talk Navy-talk’. It is fairly certain that no other author of that period would have dared to turn round and laugh in our faces like that, and it would be interesting to know how Kipling acquired this singular sureness of touch.”

While one may take issue with Captain Bethell’s order of merit for naval writers, his point about the verisimilitude of the conversation, and, this author would add, of the whole ambience conveyed by the story teller, is what makes Kipling’s naval writings so utterly real, whether they have ‘littery’ merit or not.

[A.J.W.W.]

©Alastair Wilson 2007 All rights reserved