In 1896, Kipling left Vermont and the house that he had built there, Naulakha, for England. The circumstances of his departure are well known. He was never to return.

This paper was inspired by a short stay at Naulakha, which, as has been reported previously in the Kipling Journal, is now owned by the Landmark Trust USA and is available for short-term rent. The paper’s aim is to describe the house as it stands today, in particular reporting on what remains from Kipling’s occupation. However, first it will relate the story of Naulakha from 1896 to today and of some of the people associated with it.

Naulakha’s story

Kipling left Naulakha on 29 August 1896, leaving New Jersey for England aboard the Lahn three days later. (1) Coachman Matthew Howard and his family, who lived above Naulakha’s carriage house, were left to look after the house. Kipling seems to have had every intention of returning eventually to Naulakha, since he made no effort to remove furniture and no attempt to buy a home in England, Rock House, Torquay being a one-year lease and The Elms, Rottingdean taken for three years only. (2) He maintained an interest in Naulakha, for example receiving reports that a barn, under construction when he left, had been completed. (3) However, the Beatty Balestier affair continued to rankle and over a year later, Carrie told their good Brattleboro friend Molly Cabot, somewhat exaggeratedly, ‘As Mr Kipling never talks of Brattleboro or reads a letter from America or does anything that might remotely remind him of that last year of calamity and sorrow,’ she had not shared with him news of her sister Josephine’s engagement to Theodore Dunham. (4) She continued:

‘But all the events of the last year with the leaving of Naulakha as we did leaves us sore and bruised and it takes us longer than the rest to forget…I hope you keep an eye on Naulakha and its advancement. I have a mother’s pride in its not falling back, which with Howard there does not seem possible. I hope very much that Mr. Kipling will want to return, and see no reason, under certain changed conditions, why we should not—it’s the conditions I doubt.’

Mary Rogers (‘Molly’) Cabot was a scion of an old New England family and was later the author of The Annals of Brattleboro, which summarised the lives of many local notables, including Kipling.(5) In an undated entry in her journal around this time, Molly noted ‘To Maplewood. Driving home Beatty told me that the Kiplings should never return, unless to litigation and humiliation in the courtroom.’ (6)

At the end of 1897, Carrie wrote to Molly

‘I think often and longingly of dear Naulakha as the year brings round the festivals we so rejoiced to celebrate there. But there seem to be nothing gained in a return until one may hope for a change at Maplewood’ .(7)

In the same letter she writes of how Josephine is ‘always full of a great longing for Naulakha’ and that ‘Howard writes of many things being done but his letters are characteristic and so full of a great reserve’. A further year later, thanking Molly for a photograph (subject unknown), Carrie wrote ‘The photograph continues its first impression of delight in both our minds and the balancing depression and longing for life at Naulakha again’.(8)

By 1899, Kipling was ready to make a temporary return to the USA and he arrived in New York with Carrie and the children on 2 February.(9) The following day the Vermont Phoenix newspaper speculated

‘A probable sign of Rudyard Kipling’s return to this town is the fact that his coachman has already purchased a horse to be driven with the one owned by him. The pair formerly owned by Mr Kipling was sold when he left Brattleboro’.(10)

On 11 February, an Associated Press dispatch alleged that Beatty Balestier would institute a suit for $50,000 against Kipling for defamation and false arrest. No such suit was initiated but Beatty had intimated this was his intention in an interview with the Boston Globe. (11) On the 13th, a number of prominent Brattleboro citizens wrote to Kipling expressing their earnest wish ‘that you will visit Brattleboro, and also that you will find it agreeable to make your residence here, as hitherto.’ Kipling replied graciously, concluding ‘The shortness of my visit to America will prevent me from coming up to Brattleboro at present. I trust that later on this might be possible’. (12)

On the 16th, Kipling wrote to Dr James Conland, Brattleboro physician and close personal friend, ‘The kiddies are getting better and so’s Carrie but it’s slow work. Keep me posted on any happenings of interest up in Brattleboro and I’ll let you know when I’m on the move to Boston’. (13) Four days later, he fell seriously ill.

The story of the weeks that followed has often been related, although perhaps less frequently that part reported by the Phoenix on Friday, 10 March. ‘It was the plan on Tuesday to move him from his sick room to another room in the hotel, which Mrs Doubleday had fitted up for him in reproduction of his favorite room at “The Naulahka”’

(sic). (14) ‘The hotel’ was the Hotel Grenoble and ‘Mrs Doubleday’ would have been Nellie, wife of Kipling’s publisher Frank Doubleday. Throughout Kipling’s long recuperation, the Phoenix published speculative rumours that he would visit Brattleboro, finally accepting on that he would not on 26 May,

when it wrote:

‘Why Mr Kipling Will Not Come to Brattleboro. Rudyard Kipling will not visit Brattleboro before his return to England. All the arrangements for such a visit had been made and the family were to have come on Saturday of last week, but in the meantime it became known to the Kipling family and their intimate friends that a threat had been made that there would be trouble were Mr Kipling to come here’. (15)

H. H. McClure, cousin and employee of S. S. McClure, partner of Doubleday, had visited Brattleboro on Kipling’s behalf on 25 March. The Phoenix reported that he came

‘Saturday night for the purpose, evidently, of visiting the home of Rudyard Kipling. He was met at the Brooks House Sunday morning by Mr. Kipling’s coachman, who took him to the Naulakha, where he remained all day.’ (16)

Carrie also visited Brattleboro with her mother, arriving on 8 June and returning to New York two days later. According to the Phoenix, she visited Naulakha (17) although according to her diary she did not sleep there. (18) On 14 June, the Kiplings sailed for England, never to set foot in the United States again. Matthew Howard remained in place. Later that year he travelled to England with his wife, bringing a much-treasured portrait of Josephine with him. (19) The Phoenix suggests that the visit was also to discuss the future of Naulakha. (20)

They returned, and in the 1900 US census the entry for the Howard family is next to that for Beatty, Mai and Margery Balestier, still across the road at Maplewood. (21) In the 1901 Brattleboro directory (the earliest one yet digitised) there is an entry for ‘Kipling’s Naulakha’, apparently showing it as occupied by Anna S. Balestier, Carrie’s mother. (22) In September 1900, Carrie wrote to Frederick Norton Finney, the railway owner who had provided information for Captains Courageous, of their intention to sell Naulakha as they did not wish to return to it. (23) Kipling himself wrote to Finney the following year, referring to this and to the death of Josephine, adding ‘It will be long and long before I could bring myself to look at the land of which she was so much a part’. (24) Power of attorney over Naulakha was granted to Frank Doubleday in December that year. (25)

In October 1901, the Phoenix reported that Naulakha had been ‘in the hands of agents in the big cities for many months’, implying that the asking price, in the vicinity of $25,000, was way too high. (26)

In June 1902, Kipling wrote to Conland saying ‘We are getting some things out of Naulakha bit by bit to be sent over’. (27) He asked Conland to retrieve a sextant which Conland had given him (Conland had provided Kipling with much nautical background to Captains Courageous). Conland was to pack the instrument, as ‘Howard wouldn’t know how to do it’, and ship it to England. In exchange, Conland could have, or give to his son Harry, some guns and a fishing rod “in my room” (presumably the study). The following month Kipling wrote to Carrie’s mother Anna Balestier, suggesting that she might care to offer Josephine, Carrie’s sister, some chairs, one of which was a small one which had been used by Kipling’s daughter Josephine. (28) He also asked her to check if the children’s toys had been packed up and sent away and enquired about books and china also being sent.

The house was advertised for sale in the July 1902 edition of Country Life in America, published by Doubleday. No price is mentioned.

Courtesy of The Landmark Trust USA

Kipling wrote to R G Hardie of Brattleboro in September 1902 offering Naulakha and its contents for $10,000. In the letter he notes:

‘There are two Tiffany stained glass windows in the room which was my study, and also a rather well carved teak cornice which would go with the house’. (29)

Carrie had noted in her diary in October 1893 that Naulakha had cost over $11,175 to build alone. By 1903, Kipling was desperate to sell Naulakha, In January, he wrote to Conland

‘I feel now that I shall never cross the Atlantic again – all I desire now is to get rid of Naulakha which I am perfectly willing to part with for $5000 (five thousand dollars!). This means carriages, sleights (sic) etc. and everything that may be in the house at the present time!… Perhaps the Asylum might like to buy it as an annex for their local lunatics’. (30)

Whether this low price was ever publicised, I do not know, but Naulakha was eventually bought in November 1903 by Molly Cabot, although with the intention that it would belong to her sister Grace and her husband Frederick Holbrook II (‘Fred’). Grace wrote to Molly ‘Fred’s letter makes it clear to you why he wants it in your name for the present’, although she did not expand on what that reason was. (31) Carrington gives the sale price as $8,000, speculating that a threat by Beatty Balestier to dispute title was the reason why there had been so little interest. (32) Grace Cabot’s father wrote to her ‘The property seems a bargain at the price and may well some day sell for double or treble’. (33) Grace also wrote that

‘Carrie Kipling has written Mr. Doubleday that she wants Mr. K’s desk and one or two other things from the house. Mr. Doubleday has power of attorney to sell the house so we can get it any day provided the Fitts’ [Clark C Fitts, Brattleboro lawyer] end of it is satisfactory. The relief of the Kiplings from constant expense will be their compensation. The entire contents of the barn in which Howard lives goes to him… I hope you will soon hear from Fitts so this thing can be settled and I hope Beatty won’t set fire to the house….’ (34)

In her diary, Carrie notes a trip to Tunbridge Wells on 21 November ‘to sign the deed of Naulakha.’ (35)

The Holbrooks took possession of Naulakha in November, Doubleday allowing this to occur before the deeds had crossed and recrossed the Atlantic. The same month, Grace wrote ‘Fred hopes Howard will stay at Naulakha all winter, and if we could arrange matters for a moderate sum it would be better to have him permanently’. Howard was still there the following January, when Grace wrote to Molly ‘Howard is part of the poetry of the place’. (36) Howard did eventually leave, being the proprietor of a livery stable in Brattleboro in 1910 and later a dairy farmer. (37) He died in 1929. (38) Frederick Holbrook II (‘Fred’) was a grandson of Frederick Holbrook, a prominent Brattleboro permanent resident, Governor of Vermont during part of the Civil War and a friend of Kipling. Fred’s cousin Emmerline was an artist and stayed at Naulakha in late 1894 where she painted the portrait of Josephine already mentioned. (39) This once hung over the fireplace in Carrie’s room at Naulakha (see, for example, illustration 18 in Birkenhead (40) and is now on display in the Children’s Bedroom at Batemans.

The Holbrooks made a number of changes to the house, including building two three-storey extensions on the west front cantilevered above the ground floor, adding a matching double-storey verandah at the north end and constructing a deck against the east front. The study was extended into the extra ground floor space although the original exterior and interior fabric was reused (or stored nearby). The walls between the loggia and Carrie’s room were also removed to give a larger living area. The kitchen was moved into the cellar and a dumb-waiter installed; the former kitchen being divided into a study and a pantry. (41)

The 1896 barn was also significantly extended and a swimming pool constructed past the formal garden to the south. A large terrace was also constructed at the end of the path to the south property boundary, displacing Kipling’s original small octagonal summer house. (42)

Fred Holbrook died in Paris in 1920 and Grace died in1929. (43) In 1923, Molly Cabot sold the property to their son, (Frederick) Cabot Holbrook. Molly herself died in 1932. (44) The Holbrooks continued to use the house as a summer retreat until 1942, after which it remained unoccupied. (45) In 1947, Kipling’s daughter Elsie Bambridge travelled to the United States on board the Queen Elizabeth to visit her Dunham cousins. (46) She came to Brattleboro to visit her birthplace. (47) The house and garden were open on occasions to visitors during their long period unoccupied, evidenced both by an undated tourist leaflet in the possession of the Landmark Trust USA and by a piece in the Phoenix in August 1955 announcing that Naulakha was one of a number of Brattleboro gardens open the following Saturday for a charity event. (48)

Cabot Holbrook died in 1974 and Anna his wife in 1992. (49) However, Naulakha had since 1955 been owned by Scott Farm Inc., which also owned the Holbrook family interest in Scott Farm, which adjoins Naulakha to the north and is now also owned by the Landmark Trust USA.

David Tansey, a Vermont expert in historic preservation, had worked for the Landmark Trust in the UK in the 1980s: he writes:

I was the first American to work for the Landmark Trust having begun as a volunteer in the early 1980s. I worked one year for the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation in the mid-1980s during which time I learned of Naulakha and its neglected state. The US National Trust, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now mercifully called Historic New England), and even the State of Vermont had turned it down as a project when offered the property at no cost.

When I returned to the UK to work for Landmark as project director at Crownhill Fort, I told them about Naulakha and its need for Landmark treatment. Sir John Smith sent me back to Vermont to do some research and make inquiries. In May of 1992–coincidentally on my birthday–Landmark purchased RK’s estate and an additional 18 acres.

Landmark asked me to prepare a full report which grew into the National Historic Landmark nomination that was accepted in 1992–this is our highest historic designation. While researching, I discovered a reference to a collection of RK materials in a house in Brattleboro connected with Mary Cabot who was a great friend of RK and purchased Naulakha from him. The collection, which included original architectural drawings along with some specifications, many pictures, several original letters, etc. was still there and, after a long and difficult negotiation on my part, was purchased by Landmark. Elsewhere I even discovered advertisements from the Boston paint company that had supplied Kipling; the ads featured Naulakha.

It was all so exciting and such a privilege to be part of that. Only Landmark would have taken on such a project and seen to it that it was done well.

Under Tansey’s enthusiastic management, the Landmark Trust USA restored the house, outbuildings and grounds largely to their original appearance, including original woodwork and fittings which had been in storage for eighty years. Only the absence of shutters materially differentiates the exterior of today’s Naulakha from that that Kipling built. Well over 90% of the interior finishes, plaster, panelling, window and door surrounds, etc., is original. (50) Naulakha opened to paying visitors in late 1993 and restoration work continued on the carriage house, barn and grounds.

Naulakha today

Naulakha is approached, now as then, uphill through the pine woods from the Connecticut River valley north of Brattleboro.

The way leaves Putney Road in the valley at the site of the Waites Farm, where today a Vermont Historic Sites Commission sign (with the name Naulakha misspelt) stands not far from the Kipling Theater, a cinema which closed in 2011. What was Pine Hill Road is now, fittingly, Kipling Road. First Bliss Cottage and then Beechwood, the family home of the Balestiers, are passed, both much altered, before Naulakha appears high on the left hand side. The two stone gateposts supporting the ironwork gates with a fleur-de-lis motif still guard the entrance; as does a sign from the Holbrook era reading “Private Grounds – Not Open to the Public”. Beatty Balestier’s Maplewood, originally just past the gates on the right hand side of the road, was burnt to the ground in 1904 and a new house now stands on the site. (51)

The driveway curves upwards past the barn and the carriage house, both clad in the same sage green shingles as the house itself. The white pines Kipling planted as small saplings flanking the driveway have today grown into great trees. The driveway ends at the carriage porch on the west (uphill) front of the house, from where Naulakha is entered through the original stable–type front door.

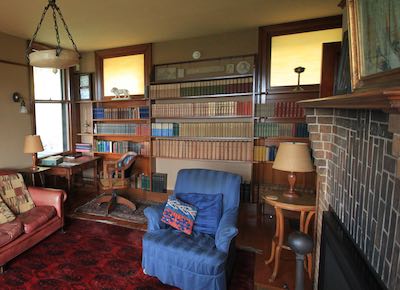

Kipling’s study at the ‘bow’ of the house is the obvious place to start to explore. Here, the Landmark Trust has thoughtfully provided a folder containing much useful information about Naulakha. The bookshelves contain a full 36 volume set of the Outward Bound edition of Kipling, the collected works of many American authors and many books about both Kipling and about Vermont.

The 1890s picture is from Marlboro College. (53) One corner of this room is particularly familiar from the often reproduced photograph of Kipling posing there, pipe in mouth. The shelving is original, although the books and the ornaments are not. The plaster statue of Grey Brother in the photograph, given to Kipling by Joel Chandler Harris, is now in the small attic museum described later. The plaster frieze in the photograph is no longer in the house, although a number of smaller casts hang in its place today, absent any obvious indication of maker. A crude wooden revolving bookcase is readily identifiable from Kipling’s own photographs of the room. Across the upper part of the east-facing bay of the study is the carved teak cornice given to Kipling by Lockwood de Forest, the furniture designer and artist. (52)

Lockwood Kipling’s most well-known contribution to the house during his 1893 visit was the plaster-work quotation from St John’s gospel ‘The night cometh when no man can work’ laid on the brick fireplace. Now slightly chipped but still fully readable, it would appear to have survived Carrie’s instructions for it to be removed. (54) Carrie was more successful in having Longfellow’s words “Oft was I weary as I toiled at Thee”, which Kipling had inscribed, removed from the first desk he had used at Naulakha (not the one in the ‘pipe’ photograph). (55) This desk, a roll-top, is now in the attic museum, minus its inscribed roll-top.

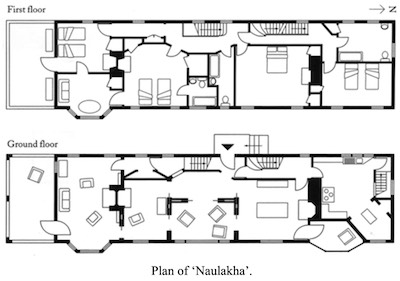

Next door is the room in which it is said Carrie kept watch for anyone attempting to enter the study when Kipling was at work. Contrary to some accounts, the study does have an entrance from the hall as well as one from Carrie’s room, as can be seen from the plan below. However, from Carrie’s desk, not now the original but similarly positioned, it would have been possible to intercept anyone heading along the hallway towards Kipling’s study.

At this point, a brief summary of the floor-plan of Naulakha, as it is today, will probably be of use.

image • courtesy of The Landmark Trust USA

The house consists of two main floors, together with a cellar and attic. Each of the main floors has a corridor along much of the west side, interrupted only by the main door, the stairwells and a door on both floors isolating the functional areas at the ‘stern’. The main rooms are all on the east side. On the ground floor from south to north are found consecutively Kipling’s study, Carrie’s office, the loggia, the dining room and the kitchen. Upstairs, the same run is from nurseries (day and night) to the servants’ rooms via the main bedroom, the bath-room and the guest bedroom. Today the night nursery and one of the servants‘ rooms make up the four rooms which accommodate up to eight adult guests. There is also a second bathroom at the north end which was formerly another staff bedroom. Kipling’s original L-shaped bathroom, which was of considerable importance to him, was split by the Holbrooks into two; one containing the original toilet and the other the original and sizeable bath, with additional but near-contemporary suite items added to each room. This is just about the only major post-1896 alteration which the Trust has not reversed, for the convenience of modern day guests who presumably have greater qualms over sharing bathrooms than had Kipling with Conan Doyle or other Naulakha visitors. (56)

Returning to Carrie’s room, we find on the wall two picture frames

known to have been Kipling’s and to which the Holbrooks subsequently affixed small plaques reading in two lines “Rudyard Kipling/Naulakha”. One frame contains seven original illustrations for ‘Mrs Hauksbee Sits Out’ (Illustrated London News, 1890) drawn by A. Forestier. The other contains the watercolour of ‘the Camel Corps’ mentioned in Carrington. (57) From the uniform, especially the grey tunics, the force illustrated would appear to be the corps raised in Sudan in 1884–5 in an attempt to support the relief of Khartoum. (58)

Next in line is the loggia. Given the cool autumn weather, I did not slide the large picture window up and “let all the woods and mountain in on me in a flood”. (59) However, the interior décor of sage green shingles did indeed convey Kipling’s intended impression of an inverted porch.

Passing through the large sliding doorway to the dining room, we find Kipling’s original table, sideboard and china cabinet. The sideboard was made by, and may well have been another gift from, Lockwood de Forest and is “a solid, emphatically rectilinear piece made of oak and accented with panels of carved teakwood”. (60) It can be identified from period photographs.

An exterior door leads from the far side of the dining room to Kipling’s ‘little overhung verandah to play in’. (62) A two-way sprung door leads to the butler’s pantry/kitchen corridor, which in turn leads to the back stairs and to the kitchen. In the kitchen, the most notable survivor is a large sheet-steel stove hood, into which a smaller, modern extractor hood is now cunningly fitted. Stairs from the kitchen lead down to the scullery and to the cellars.

Upstairs on the landing are hung a number of coloured French military etchings, also tagged as Kipling’s. They are by the prominent military artist Edouard Détaille and are mainly of individual soldiers, although one depicts an escort platoon of cuirassiers from 1885 in a street scene used by Détaille in his L’Armée Francaise: Illustrated History of the French Army 1790–1885. (64) Kipling’s reference to Détaille in chapter four of The Light that Failed is described in Richard Berrong’s article in the March 2013 edition of the Kipling Journal. (65) Carrington states that the prints were a gift from Détaille, although as they were left in Vermont, Kipling’s attachment to them may not have been great. (66)

In the main bedroom at Naulakha is a watercolour of a two-storey white house set against a wooded background. It carries the initials ERC, the date 1894 and also one of the Holbrooks’ small plaques. This is most probably by Edith Raymond Catlin, who the Kiplings met along with her mother and sisters in Bermuda in 1894. (67) She later ainted under her married name of Edith Catlin Phelps. Cabot Holbrook wrote about this picture to Carrie Kipling in 1938, although he misread the initial as EBC and did not know its origin. (68) Also bearing a plaque is a plate from Ruskin’s ‘The Bible of Amiens’. All of the furniture in the room is original, with the exception of one bedside table. (69)

To the north, in the part of the original bathroom which is en-suite to the main bedroom, may be found Kipling’s original claw-footed bath, its wooden surround replete with the Holbrook tag of originality. To the south, a door leads to the day-nursery, now a delightful morning room lit from the east via its bay window. On the right of the door is a small piece of raised plasterwork by Lockwood Kipling of two birds and a cat amongst the branches of a tree.

From the upper verandah, the vista east across the valley to the New Hampshire hills still unfolds today, albeit more afforested than 120 years ago when Kipling first saw it. Monadnock’s peak can indeed be seen some 35 miles away, although it was rather more insignificant in real life than Kipling and the biographers of his Vermont period led me to expect. It may be “a gigantic thumbnail pointing heavenward” but it could certainly be hidden from view by the tip of my own thumb at arm’s length in front of me. Perhaps if I too had been brought up on Emerson, I would have experienced more of Kipling’s thrill.

No obviously ‘tagged’ Kipling items are in the night-nursery, now a guest bedroom, although David Tansey has identified some of the pieces in this room and the other bedrooms as original, based on the lists in the F. Cabot Holbrook Collection at Marlboro. The guest bedroom has another picture tagged as Kipling’s, a monochrome print of G. F. Watt’s 1886 ‘Hope’. A wall-hung plaster frieze may also be original, as the wall is unpainted behind.

The attic consists of one large room, taken up largely by a billiards table (which guests may use) and a smaller room, formerly another staff bedroom, containing in locked display cases a number of Kipling-related items. These include his golf-clubs, the Chandler Harris wolf and an accompanying Bagheera, a mail-bag inscribed ‘Naulakha’, an armadillo shell and some glass net floats supposed to have been collected by Kipling on one of his fact-finding trips for Captains Courageous. There are also a number of post-Kipling Naulakha souvenirs, including a small illustrated jug which could well be the item advertised in the Phoenix in June 1896 by crockery merchants Morris & Gregg as ‘Kipling house souvenir’, price 35c. The attic also contains a small library of Kipling-related books collected and donated by Matilda Tyler.

In the cellars, which extend for the full run of the house, is a modern boiler servicing the hot air heating system, which still warms the main rooms of the house through the ornate, original iron heating grilles in the floor. Several older boilers remain: disconnected museum-pieces for domestic heating enthusiasts. The trouble Kipling had drilling and pumping for water was told ,with copious illustrations, in the June 2011 edition of the Kipling Journal. Alas ‘Eugene’ the engine is no more, nor is his little pump house, demolished in the course of the Holbrooks’ alterations. Even the original well can no longer be used. A modern electric pump is now sited in the cellar, accessing a new well drilled to over seven hundred feet by the Landmark Trust. (70) Even so, limits to supply remain, as is highlighted by the instructions to guests affixed to the cistern in Kipling’s bathroom:

‘This is Rudyard Kipling’s toilet. It is 117 years old. Please make sure the rubber seal is properly set after you flush. If it is allowed to run, the entire water supply can be depleted in a few hours. This means the entire house will be without water. It will then take many hours for water to be available again’.

The garden which Kipling created to the south of the house, doubtless in part from seedlings provide by Vermont’s travelling ‘Pan’, is now laid entirely to grass, distinguished only with a central, low granite plinth, a legacy of the Holbrook years. Beyond it, the level walk to the property’s southern boundary is now in part a tunnel through dense rhododendrons twenty feet high, planted by the Holbrooks a hundred years ago. (71) The Holbrooks’ swimming pool has been filled in and grassed over.

At the path’s end, where once stood Kipling’s small wooden gazebo, is the Holbrook-added terrace, in a classical style with a stone summer house and arch. The original octagonal gazebo is now located lower down the slope, past wood piles (cut logs rather than brushwood, alas), next to the original 1894 clay tennis court. This had gone to grass but, as noted in this journal, was restored to playing condition in 1997. (72) The rest of the grounds to the east, which slope down to the tree-lined Kipling Road, are kept as meadow land, where once we caught sight of a fox hunting energetically for its breakfast in the early morning dew.

The stables, over which the Howards once lived, were occupied until 1995 by Cabot Holbrook’s daughter, Mary Cabot Panzera, and her husband.(73) In front is the former ice-house, now used as a shed. Further down the driveway is the barn, which now serves as a museum about Kipling’s time in Vermont and contains such relics as a wheel of the ‘red phaeton’ which Carrie used to drive with Howard behind in full English coachman’s livery, Kipling’s snowshoes and the remnants of a large sled, together with an evocative photograph of Howard and his children using on the slope below the house.

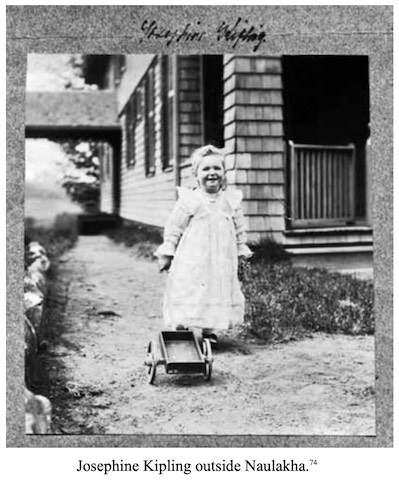

A purist might baulk at Naulakha being a holiday let rather than a museum like Batemans. However, as a means of helping the present generation on both sides of the Atlantic to understand the Kipling of that time, I can think of nothing more appropriate than this total immersion in his environment. A view obviously shared by Kim Cattrall, who recorded in Naulakha’s visitors book that she stayed here in 2007 when preparing for her part as Carrie in the BBC production of ‘My Boy Jack’. Perhaps the most poignant entry, however, was one which echoed Kipling’s own fears: ‘I’m quite convinced I saw the little spirit of Kipling’s ‘Best Beloved’ walking about the halls at night a few times. Perhaps little Josephine still lives here?’ (74)

photo • courtesy of The Landmark Trust USA

Acknowledgements

I would particularly like to acknowledge the help I received in compiling this article from David Tansey, who most kindly read and proposed improvements to my early drafts. I would also like to thank Emily Alling of Marlboro College, Vermont, Gary Enstone at Batemans, the staff of the Special Collections department at the University of Sussex and Kelly Carlin at The Landmark Trust, USA.

Notes

1. S. Murray, Rudyard Kipling in Vermont, Bennington, VT, Images from the Past Inc., 1997, pp.158,161.

2. A. Lycett, Rudyard Kipling: A Biography, London, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1999, pp.397, 407.

3. T. Pinney, Editor, The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vol. 2, London, Basingstoke, Palgrave MacMillan, 1990. Letter to James Conland, 1–6 October, 1896, p.250.

4. M.R. Cabot, ‘The Vermont Period: Rudyard Kipling at Naulakha’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, Volume 29, Number 2, 1986, pp.161–218.

5. H.C. Rice, ‘Brattleboro in the 1880’s and 1890’s: Cabots, Balestiers, and Kiplings’, English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, Volume 29, Number 2, 1986, pp.150–160.

6. Cabot op. cit.

7. ibid.

8. ibid.

9. Lycett op. cit., p.421.

10. Vermont Phoenix, 3 Feb 1899, Library of Congress.

11. Cabot ibid.

12. ibid.

13. ibid.

14. Vermont Phoenix, 10 Mar 1899.

15. Cabot op. cit.

16. Vermont Phoenix, 31 Mar 1899.

17. Vermont Phoenix, 9 Jun 1899.

18. C. Carrington, ‘Notes on Carrie Kipling’s diary’, SxMs41/2/1-6 (Kipling Papers, University of Sussex, Special Collections).

19. ibid.

20. Vermont Phoenix, 17 Nov 1899.

21. . US census 1900, Dummerston, Windham, Vermont; Roll: 1695; Page: 4B; Enumeration District: 0249, Ancestry.co.uk.

22. Brattleboro Directory 1901, Ancestry.co.uk

23. Cabot op. cit.

24. ibid.

25. Carrington, ‘Notes on Carrie Kipling’s diary’ (see n.12).

26. Vermont Phoenix, 21 Oct 1901.

27. T. Pinney, Editor, The Letters of Rudyard Kipling. Vol. 3, Letter to James Conland 13 June 1902, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 1997, p.91.

28. . ibid. p.97, Letter to Anna Smith Balestier, 4 July 1902.

29. . Cabot op. cit.

30. Pinney. Vol. 3, Letter to James Conland, 27 January 1903, p.123.

31. Cabot op. cit.

32. C. Carrington, Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work, Penguin, 1986, p.433.

33. Cabot op. cit.

34. ibid.

35. C. Carrington, ‘Notes on Carrie Kipling’s diary’, SxMs41/2/1-6.

36. Cabot op. cit.

37. US censuses 1910, 1920, Brattleboro,

38. Vermont Death Records, 1909–2008

39. Pinney. Vol. 2. p.170, Letter to Ripley Hitchcock, 22 January 1895 (footnote 1).

40. Lord Birkenhead, Rudyard Kipling, London,Weidenfeld and Nicholson Ltd, 1978.

41. D. Tansey, 1993, Naulakha: National Historic Landmark Nomination, (https:// pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NHLS/Text/79000231.pdf) and e-mail from David Tansey to the author, 18 December 2012.

42. Tansey op. cit. and Box 11, Folders 14 & 15, F. Cabot Holbrook Collection, Marlboro College, Vermont.

43. C. Kayley, Record and photograph on www.findagrave.com.

44. Vermont Death Records, 1909–2008

45. Tansey op. cit.

46. UK Outward Passenger Lists, 1890–1960 Queen Elizabeth, 25 Jul 1947.

47. Cabot op. cit.

48. SxMs41/7/1-3.

49. Kayley op. cit.

50. e-mail from David Tansey to the author, 4 January 2013.

51. Cabot op. cit.

52. Cabot op. cit.

53. F. Cabot Holbrook Collection, Marlboro College, Vermont.

54. G. Ireland, 1948, The Balestiers of Beechwood Privately published.

55. Murray op. cit. p.170. Murray, possibly following Ireland, quotes the inscription as “…as I toiled..”, although Longfellow has “…when I toiled …” (‘The Broken Oar’ in A Book of Sonnets).

56. The Landmark Trust (undated), Naulakha House Tour Guide.

57. Carrington, Rudyard Kipling, p.99.

58. D. Johnson, Sudan: The Desert Column 1884–5 .

59. Pinney, Vol. 2. p.105, Letter to Margaret Mackail, August 1893.

60. R.A. Mayer, Lockwood de Forest: Furnishing the Gilded Age with a Passion for India, Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 2008.

61. F. Cabot Holbrook Collection, Marlboro College, Vermont.

62. Pinney, Vol. 2. p.89, Letter to Margaret Mackail, February 1893.

63. F. Cabot Holbrook Collection, Marlboro College, Vermont.

64. E. Detaille (trans. M.C. Reinertsen) (1992, original published 1885–1889), L’Armée Francaise , New York: Waxtel & Hasenauer.

65. Kipling Journal, No. 349, March 2013, p.25.

66. Carrington op. cit. p.299.

67. Lycett op. cit. p.355.

68. Copy of letter of 10 February 1938, and reply of 19 February, in file in study desk drawer at Naulakha.

69. e-mail from David Tansey to the author, 4 January 2013.

70. e-mail from David Tansey to the author, 18 December 2012.

71. Box 11, Folders 14 & 15, F. Cabot Holbrook Collection, Marlboro College, Vermont.

72. Kipling Journal, No. 282, June 1997, p.44.

73. e-mail from David Tansey to the author, 18 December 2012.

74. F. Cabot Holbrook Collection, Marlboro College, Vermont.

[M.K.]

©Mike Kipling 2013 All rights reserved