Contemporary criticism

From the outset, “McAndrew’s Hymn” attracted much critical attention. Kipling. The Critical Heritage (ed. Roger Lancelyn Green, Barnes and Noble 1971) provides five comments on the poem, all dating, roughly, from the period when it was first published.

- Charles Eliot Norton, writing in the Atlantic Monthly, Jan 1897.

“And so vivid are his appreciations of the poetic significance of even the most modern and practical of the conditions and aspects of sea life, that in “McAndrew’s Hymn”, a poem of surpassing excellence alike in conception and execution, Mr. Kipling has sung the song of the marine steam-engine and all its machinery, from furnace-bars to screw, in such wise as to convert their clanging beats and throbs into a sublime symphony in accord with the singing of the morning stars.”

And, “Such a poem as “McAndrew’s Hymn” is a masterpiece of realism in its clear insight into real significance of common things, and in its magnificent expression of it.” - Letter from Lafcadio Hearn to Ellwood Hendrick, Feb 1897. “… Oh! Have you read those two marvellous things of Kipling’s last [referring to The Seven Seas] – “McAndrew’s Hymn” and “The Mary Gloster”.

- “The Works of Mr. Kipling”, by J.H. Millar, writing in Blackwood’s Magazine, October 1898.

“…“The Flag of England”…“McAndrew’s Hymn” – these are strains that dwell in the memory and stir the blood. They have a richness and fullness of note very different from the shrill and reedy utterance of many who have attempted to tune their pipe to the pitch of courage and patriotism.” - “The Madness of Mr. Kipling, by ‘An Admirer’ in Macmillan’s Magazine, Dec. 1898. The author has been identified as S.L. Gwynn.

“…“McAndrew’s Hymn” makes interesting reading, no doubt, but it also misses being poetry, because Mr. Kipling is too much set on the detail and cannot hide his knowledge; what he wants to celebrate is power, and he only shows us the machinery.” - “The Poetry of Mr. Kipling”, by Edward Dowden, writing in the New Liberal Review, February 1901.

“And in the true beat and full power of his engine, with faithfulness in every crank and rod, McAndrew reads its lesson and his own:’ Law, Orrder, Duty an’ Restraint, Obedience, Discipline!’

“The ‘reigning personage’ … of Mr. Kipling’s creations is the man who has done something, of his own initiative (or of God’s), if he be a man of genius; and if not a man of genius, then something which he finds like the brave McAndrew – and he is almost a genius – allotted or assigned to him as duty.”

“The Viscount loon who questioned McAndrew as to whether steam did not spoil romance at sea is very summarily dismissed; it is feebleness of imagination which has no sense of the world-lifting joy that still comes to cheer man the artifex, and a dream, not of the past, not of hide-bound coracle or beaked trireme, but of the Perfect Ship still lures him on. Our miracles are those which subdue the waves, and fill with messages of fate the deep-sea levels, and read the storms before they thunder on our coast, and toss the miles aside with crank-throw and tail-rod. ‘Gross modern materialism!’ sighs the votary of romance feminine; and such it may be for him, but such it is not for those who with masculine imagination and passion can perceive that it is the dream of the artifex which subdues and organises and animates the iron and the steel. We may sell a creel of turf in a sordid and grasping spirit, and we may design a steam-ship with something like the enthusiasm of a poet.”

T S Eliot on the poem

Also in The Critical Heritage, but from a period when Kipling was, in critical terms at least, regarded as being ‘played out’, T S Eliot, in “Kipling Redivivus”, review of The Years Between, in the Athenaeum, May 1919, comments:

“And this is why both Swinburne’s and Mr. Kipling’s verse, in spite of the positive manner which each presses to his service, appear to lack cohesion – to be, frankly, immature. What is the point of view, one man’s experience of life, behind “Mandalay” … and “MacAndrew””? (sic)

In 1941, some 20 years later, Faber and Faber published A Choice of Kipling’s Verse made by T.S. Eliot. In an introductory essay, Eliot discusses “McAndrew’s Hymn” saying that “it is in two poems extremely unlike Browning’s in style – “McAndrew’s Hymn” and “The Mary Gloster” – that Browning’s influence is most visible. Why is the influence of Swinburne and Browning so different from what you would expect? It is due, I think, to a difference of motive: what they wrote they intended to be poetry; Kipling was not trying to write poetry at all.

There have been many writers of verse who have not aimed at writing poetry: with the exception of a few writers of humorous verse, they are mostly quickly forgotten. The difference is that they never did write poetry. Kipling does write poetry, but that is not what he is setting out to do. It is this peculiarity of intention that I have in mind in calling Kipling a ballad-writer …”

Eliot writes a few pages later “It would be a mistake, also, … to suppose that the audience for balladry consists of factory hands, mill hands, miners and agricultural labourers. … On the other hand, the audience for the ballad includes many who are, according to the rules, highly educated.

He goes on, “What is unusual about Kipling’s ballads is his singleness of intention in attempting to convey no more to the simple-minded than can be taken in on one reading or hearing. They are best when read aloud, and the ear requires no training to follow them easily. With this simplicity of purpose goes a consummate gift of word, phrase, and rhythm.”

When talking about “Danny Deever”, Eliot says: “There are other poems in which the element of poetry is more difficult to put one’s finger on … Two poems which belong together are “McAndrew’s Hymn”, and “The ‘Mary Gloster’” … They are dramatic monologues, obviously, as I have said, owing something to Browning’s invention, though metrically and intrinsically ballads. The popular verdict has chosen the first as the more memorable: I think that the popular verdict is right, but just what it is that raises “McAndrew’s Hymn” above “The ‘Mary Gloster’” is not easy to say. The rapacious old ship owner of the latter is not easily dismissed, and the presence of the silent son gives a dramatic quality absent from McAndrew’s soliloquy. One poem is no less successful than the other. If the McAndrew poem is the more memorable, it is not because Kipling is more inspired by the contemplation of the success or failure than by that of the failure of success, but because there is greater poetry in the subject matter. It is McAndrew who creates the poetry of Steam, and Kipling who creates the poetry of McAndrew.”

Angus Wilson

In the 1970s there was a mention of McAndrew in Rudyard Kipling, by Martin Fido, (Hamlyn Publishing, 1974.) “On trials in a new destroyer … he was thrilled and impressed by the practical example of the romance of steam, and delighted to discover that all the engineers knew his poem “McAndrew’s Hymn”.” This comment was identified in The Strange Ride of Rudyard Kipling by Angus Wilson (Martin Secker and Warburg, 1977) as coming from a letter to Doctor Conland. Wilson thought highly of “McAndrew’s Hymn”.

“But the finest celebrations of machines are to be found in his two imitation Browning monologue poems, “McAndrew’s Hymn” (1893) and “The Mary Gloster” (1894). And here he celebrates not the machines, but the men who work them – a Scots ships’ engineer and a hard old tough-living, rich ship-owner on his death-bed. Both are positive hymns to the life force. They work perfectly. And one sees well why a man who could encompass the whole meaning of an individual life in a single poem would find the intricacies and necessary longueurs of novel-writing uncongenial.”

“It was Kipling’s corollary to the philosophy of self-reliance to expound the relation of the man to the machine in the new industrial age. The engineer, more than most men, is a master because, in Emerson’s awkward phrase, he is ‘plastic and permeable to principles’.

Wilson then quotes:

“From coupler-flange to spindle-guide I see Thy hand, O God:

Predestination in the stride o’ yon connectin’ rod.

John Calvin might ha’ forged the same, enormous, certain slow –

Ay, wrought it in the furnace flame, my Institutio.”

So speaks, says Wilson, McAndrew, the Scottish engineer, of his machine, the engine of which he is at once master and servant, which conforms to the laws of nature and yet is altogether dependent on his skill and courage.”

Lord Birkenhead

The next biographer to make mention of “McAndrew’s Hymn” is Lord Birkenhead, (Rudyard Kipling, Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1978). (It is worthwhile reminding readers that the first draft of this work was originally completed in 1947, but could not be published because of the objections of Kipling’s daughter, Mrs Bambridge. It eventually came out in a revised version after the death of both Mrs Bambridge, and the author)

Referring to the year 1893, Birkenhead writes: “he was also working on “McAndrew’s Hymn”, in which he extolled the glory of steam, a poem which was to lead on to other which were to fascinate some and repel others, in which machinery talked in complex jargon – stories which were to reach their perfection in “The Ship that Found Herself” in 1895.”

For 1894, he writes: “Supreme among his verses at this time, was the poem “The Mary Gloster” – similar in form but far more successful than “McAndrew’s Hymn” – in which a villainous shipowner on his deathbed berates his effeminate son.”

It is interesting to note the opposing views of which was the better or more popular poem of the two. Eliot preferred “McAndrew’s Hymn”, while Lord Birkenhead favoured “The Mary Gloster”. Each implied that their view was shared by the public!

Peter Keating

In 1994 appeared Peter Keating’s Rudyard Kipling – The Poet (Secker and Warburg, 1994), the first, and so far only, major critical study to consider Kipling’s poetry alone. Keating says (p. 91):

“Unlike his close contemporary Conrad, who wrote primarily about the vanishing world of sailing-ships, Kipling’s imagination was excited by steam, engine-power, speed and the men who created and maintained such modern wonders. With the Scottish engineer in “McAndrew’s Hymn” he prayed that the Lord would send a man like Robbie Burns to sing the Song o’ Steam. Perhaps, for a while, he believed that he himself might fill that role, though with the genuine humility he always showed to this poet, he also described his attempts to capture the essence of the modern world as merely “roughing out the work” for a greater poet to come “as Ferguson did for Burns”.

Peter Keating also goes into greater detail about “McAndrew’s Hymn” and “The Mary Gloster” (pp. 108-110):

“They are quite distinct from the Browning parodies and pastiches he had previously written, and also unlike the music-hall types he was still using for some of the barrack-room ballads. Complex character analysis and psychological subtlety are not qualities usually associated with Kipling’s poetry, and even here in “McAndrew’s Hymn” and “The ‘Mary Gloster’, both clearly poems of character, the experiences and opinions of the speakers are more obviously imbued with Kipling’s own views than they would be in a comparable Browning monologue.

Both speakers are blunt, frank, down-to-earth. McAndrew is a ship’ engineer, content with his job since a visionary experience at sea prompted him to shed his repressive Calvinist upbringing and adopt as his replacement “Institutio” a religion of the steam-engine. As published originally in Scribner’s Magazine, December 1894, the monologue was introduced by a fictitious “extract from a private letter” which makes it clear that McAndrew is on deck reminiscing to a passenger: this setting is not apparent from the poem as printed in The Seven Seas. The passenger says that McAndrew admitted to being made “quite poetical at times” by the engines, something that is perfectly clear from the poem itself, but he also describes McAndrew as “a pious old bird”. The poem leaves open just how “pious” McAndrew is: there are hints that he is priggish, given to the sin of pride, and not as free from Calvinist morality as he likes to claim. It is this note of ambiguity about how much reliability the reader can place on McAndrew’s insight into himself that reveals the influence of Browning, and perhaps too that of Burns’s “Holy Willie’s Prayer”.

Gloster’s character is more straightforwardly observed than McAndrew’s. He is a successful shipowner, a self-made man; wealthy, honoured, “not least of our merchant-princes”. He is also coarse and mean-minded, whereas McAndrew is genuinely sensitive, if rather smug. Yet the social distance between the two men, and the contrasting moral qualities they possess, are nothing to what unites them. They are devoted to the sea and the hard life it demands from those who live by it; they are widowers and talk openly, though not boastfully, about other women they have had; both are given to grand romantic gestures; and both regard as unbearably effete any way of life other than their own. McAndrew is scathing about a visitor to the ship, “Wi’ Russia-leather tennis-shoon an’ spar-decked yachtin’ cap,” who is unable to see that McAndrew, “manholin’, on my back – the cranks three inches off my nose”, represents the true romance of the sea. Gloster’s verbal attack on his son makes a similar point, though, true to his harder character, it is more vicious and it also gives Kipling yet another chance to mock the Aesthetes.

In Browning, these sentiments and the tone in which they are expressed would destroy any credibility claimed by the speaker, whereas Kipling enlists them as allies in his campaign on behalf of manliness. Nor does McAndrew’s greater sensitivity exclude him from being similarly placed. Like Sir Anthony Gloster, the most important thing about him is that he is a true man.

These two poems have always attracted admirers, among them T S Eliot, who was drawn to Kipling’s experimental use of “the poetry of steam” in “McAndrew’s Hymn”. An experiment it certainly is, but a very self-conscious one. McAndrew’s references to “coupler-flanges”, “spindle-guides”, “furnace-bars”, and “connectin’-rods”, function within the poem more as appropriate atmosphere than realised images. The uninitiated reader may be convinced that a “spindle-guide” is important to McAndrew, but has no way of knowing why it is so significant – indeed any way of understanding from the poem what exactly it is.”

Comments in recent biographies

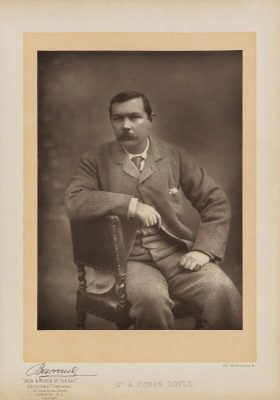

Harry Ricketts, in The Unforgiving Minute (Chatto and Windus, 1999) says, referring to the memories of Kipling by Arthur Conan Doyle:

Arthur Conan Doyle by Herbert Rose Barraud, published by Eglington & Co carbon print

published 1893 • NPG Ax27656 © National Portrait Gallery, London • NPG“Doyle’s reminiscences also afford a rare glimpse of Kipling reading his work. Earlier in the year, he had written “McAndrew’s Hymn”, a Browningesque dramatic monologue in which an ageing Scottish engineer reviewed his life at sea and his discovery of the idiosyncratic faith which had sustained him.

McAndrew revealed that, tempted by the East in his wild youth, he gave way to the Sin ‘against the Holy Ghost’: the despair that leads to suicide. He was saved, he confessed – ‘An’ by Thy Grace, I had the Light to see my duty plain./Light on the engine-room’. In other words his salvation, a typically Kiplingesque one was through work and being ‘o’ service to my kind’. Kipling’s performance of the poem sounds impressive. ‘He surprised me’, Doyle remembered, ‘by his dramatic power which enabled him to sustain the Glasgow accent throughout, so that the angular Scottish greaser simply walked the room’.”

Referring to The Seven Seas Ricketts comments:

“A few poems showed an ambitious interweaving of low-brow and high-brow elements. Speaker, idiom and milieu were calculatedly working-class in “McAndrew’s Hymn”, the engineer ‘alone wi’ God an’ these/My engines’; yet the dramatic monologue form, with its artful construction of an apparently artless narrator was literary and sophisticated. The poem imagined one kind of reader who would fuss over all the technical jargon, another who would see at once that McAndrew’s wish for ‘a man like Robbie Burns to sing the Song o’ Steam!’ was being granted even as they read. And so, rather neatly, Kipling was able to present himself as simultaneously the poetic heir of both Burns, provincial maverick, and Browning, English literary establishment.”

Finally, we come to Andrew Lycett’s Rudyard Kipling (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1999). On p. 267, Lycett reports:

“When Henry James came to stay at Tisbury, Rudyard spared him his observations on Americans abroad …. And read him his paean to a Scottish ship’s engineer, ‘McAndrew’s Hymn’, which would appear in Scribner’s Magazine in December. No doubt Rudyard, in expansive mood, adopted the broad accent of his Macdonald forebears. For this was a poem he had been working towards. He knew he could always write some ditty based on the aspirations of the soldiers’ mess, but he needed new subject matter. Over the previous two years he had been exploring the nature of romance; ‘was it really achievable in an age of season tickets?’ he asked in “The King”. As he looked back over British history, he felt this elusive quality could still be found at sea, and suggested as much in several poems in the early 1890s ranging in style from “A Song of the English” to “The Ballad of the “Clampherdown”. His personal contribution to the established genre of nautical verse was to invoke the role of machinery on the ocean wave. He achieved this in ‘McAndrew’s Hymn’, which chronicles the heroics of a ship’s engineer in command of his ‘purrin’ dynamoes’ as they beat out their message (reminiscent of Rudyard’s own politics): ‘Law, Orrder, Duty an’ Restraint, Obedience, Discipline!’”

[A.J.W.W.]