Publication

First published in The Youth’s Companion (where it is headed by the verse) in the United States of America 19 October 1893 (pp. 506-507) with three woodcut illustrations of the United Services College, where Kipling was at school from 1878 to 1882. See Charles Carrington, Chapter 3, and Something of Myself, Chapter 2. The piece was collected (with some revision by Kipling) in Land and Sea Tales (1923); also in the Sussex Edition, Volume XVI, pp. 197-215.

The ‘Public School’

The British ‘Public School’ is a paradox in that it is not public as access is restricted to those who can not only pass an entrance examination but whose parents or guardians can afford fees of the order of £20,000 a year.

Some public schools began as religious foundations in the Middle Ages and many were founded in Victorian times, including the United Services College. Maj. Gen. L C Dunsterville, the original of ‘Stalky’, writing some 50 years after his schooldays, recalls (p. 19):

The college was started about the year 1872 on a sort of co-operative principle by a lot of old Admirals and Generals who found themselves like most retired service-men unable, even in these days, to pay the high costs of public school education… The founders of the college bought a long terrace of houses at the foot of the high ground facing the sea. These were adapted to form dormitories, classrooms and quarters for the masters.

United Services College

So Eton may keep her prime ministers,

And Rugby her preachers so fine

I’ll follow my father before me,

And go for a sub of the line

The line,

And pass for a sub of the line.

[School Song]

A ‘sub’, in this context, is a Subaltern – a junior officer in the army, many of whom appear in Kipling’s stories. ‘the line’ here means the infantry regiments in the British army. This verse goes (more or less) to the tune of “The Eton Boating-Song.” Eton College, near Windsor, one of the leading English public schools, was founded by King Henry VI in 1440, Rugby School, Warwickshire, by Lawrence Sheriff in 1567. USC opened its doors in the Autumn term of 1874.

Stalky & Co.

See also George Beresford, the original of ‘Turkey’, Chapter 1, which gives a description of the buildings and general background.; also the notes in this Guide to “A Little Prep”, page 166 line 22 of Stalky & Co. Also the introductory notes on Stalky & Co. by Isabel Quigley and Lancelyn Green. There are one hundred references to these stories in the Kipling Journal, some of which are mentioned below.

The chief interest in this article lies in the fact that it was written and first published before any story in Stalky & Co. was — so far as is known — either written or thought of. Consequently, it gives a picture of the “Coll” at Westward Ho ! which is perhaps more likely to be accurate than the account in Something of Myself — or in any other subsequent reminiscences, such as those by Dunsterville and Beresford.

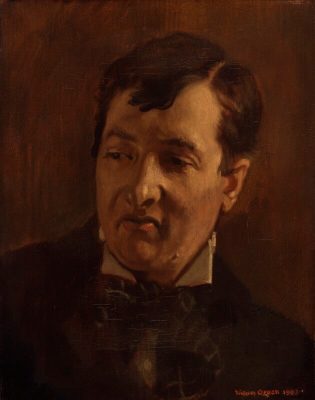

George Charles Beresford by Sir William Orpen, oil on canvas, 1903

NPG 5596 © National Portrait Gallery, London • NPG

Some critical responses

Somerset Maughan’s offers a singularly humourless verdict in “A Choice of Kipling’s Prose” (p. vi):

A more odious picture of school life can seldom have been drawn. With the exception of the headmaster and the chaplain the masters are represented as savage, brutal, narrow-minded and incompetent. The boys, supposedly the sons of gentlemen, were devoid of any decent instincts … The three of them exercised their humour in practical jokes of a singular nastiness.

A similar lack of humour is shown by George Sampson (see Isabel Quigly’s Introduction above) quoted by Charles Carrington (p. 30). Samson calls it: ‘an unpleasant book about unpleasant boys in an unpleasant school.’

“An English School” is interesting and informative, indicating that some incidents and people mentioned in Stalky & Co. are real, but it is dangerous, as Green says, to assume the same for all the stories. Stalky & Co. is, as Dunstervills says (p. 25) a work of fiction and not a historical record. Kipling himself called the stories:

‘…tracts or parables on the education of the young. These … turned themselves into a series of tales called Stalky & Co … On their appearance they were regarded as irreverent, not true to life, and rather ‘brutal.’ (Something of Myself, pp.134-5.)

Dr Tompkins, a formidable teacher in her own right, puts her finger on it – as always – when, speaking of the whole series of the ‘Stalky’ stories, she says (p. 242):

The boys that swarm through the page act and speak with complete credibility … The whole lively, grubby, community is there, with the masters irritated, supercilious, mutually intolerant, yet possessed by that unreasonable ‘caring’ of the teacher for the pupil as the recipient of his ministration, and occasionally by his need of reassurance that all his effort has not been wasted, that ‘something sticks’, as King says ‘even among the barbarians.’ This is done to the life.

Another writer who has seen the point – as many have not – is Jad Adams, whose Kipling appeared in 2005, published by Haus Books, who says of Stalky & Co. (page 19):

The stories have more literary than biographical relevance and belong to a prolific stage in Kipling’s writing career …. but it is relevant that throughout the stories … runs a conscious perception that the tricks, japes, adventures and feats of daring in which the boys take part have a real and specific relevance to the outside world.

What is clear is that Kipling’s perceptions of the values and atmosphere of United Services College, as described in “An English School”, are faithfully carried through into Stalky & Co., some six years later.

Further reading on British public schools

There is an extensive literature on real British schools as well as fictional ones:

- Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857) by Thomas Hughes (1822-1896)

- a long series of stories by Charles Harold St. John Hamilton (1876-1961) who wrote under several names, including “Frank Richards” and is credited with seventy million words. His “Greyfriars School” stories appeared in a thousand issues of The Magnet, a magazine for boys published from 1908 to 1940.

- Wikipedia has an interesting entry on ‘Billy Bunter’ and The Magnet.

- The Introduction to The Oxford Book of Schooldays, ed. Patricia Craig (OUP 1994) offers an entertaining examination of the British education system.

[J H McG]

©John McGivering 2007 All rights reserved