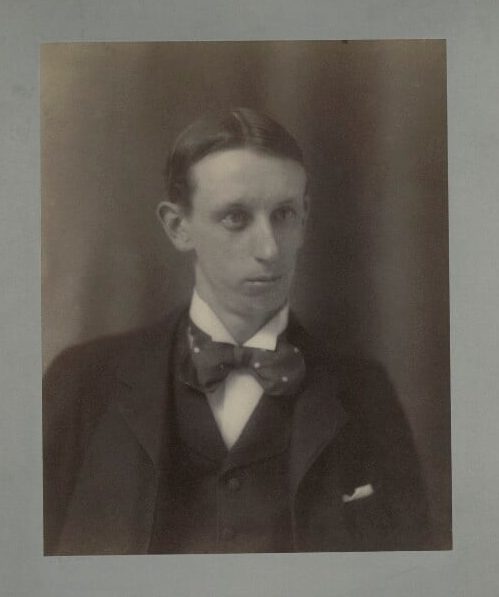

Wolcott Balestier was an American, born in 1861, who had worked as a journalist and had written three unsuccessful books. He came to London in December 1888 as the agent of the American publisher Lovell. He had two sisters, who took it in turns to come over from America to keep house for him. The elder, Caroline, was to become Kipling’s wife.

Wolcott had great charisma. Birkenhead and Carrington both give lists of the novelists, poets, critics and artists who came under his spell. Martin Seymour-Smith writes: ‘Whistler and his wife fell for Wolcott’s charm. So did Austin Dobson, Alma Tadema, George Meredith, Jean Ingelow, Kate Greenaway and a host of other luminaries’.

So I do not think there is any need, as Seymour-Smith does, to call upon homosexual attraction to explain the friendship between Wolcott and Kipling. Kipling’s mother Alice was an intelligent and experienced woman. When she met the Balestier family in London in May 1890, she only saw the attraction of Carrie (the elder of Wolcott’s two sisters) and prophesied (correctly but with no enthusiasm) “That woman is going to marry our Ruddy”.

What was Kipling’s attitude to homosexuality? When, in his old age, he looked back on his schooldays, he wrote that “Westward Ho! was clean with a cleanliness that I have never heard of in any other school.” He goes on: “I remember no cases of even suspected perversion”. Old men forget: he himself was so suspected, though he didn’t realise at the time. Lord Birkenhead’s biography quotes a letter from Kipling to Crofts, (the original of King in “Stalky & Co.”) after a visit from Dunsterville (Stalky) in India in 1886:

Dunsterville pointed out a little fact to me which has made me rabidly furious with M. H. P. [Matthew Henry Pugh, their Housemaster] You will not recollect that he once changed my dormitory – just before I left – and insisted upon the change with an unreasoning violence that astonished me. Thereafter followed a row, I think. I objected to be transferred because my little room was a snug one, had no prefect, and allowed me to spread my boxes and kit. About this time M. H. P, who must be a very Stead in his morals and virtuous knowledge of impurity and bestiality, transferred me to my old room, clearing out the other two boys who occupied it.

It never struck me that the step was anything beyond an averagely lunatic one on the part of M. H. P. – I was not innocent in some respects, as the fish girls of Appledore could have testified had they chosen – but I certainly didn’t suspect anything. Dunsterville told me on Wednesday, in the plain ungarnished tongue of youth the why and the wherefore of my removal according to M. H. P. , and by the light of later knowledge I see very clearly what that moral but absolutely tactless Malthusian must have suspected. It’s childish and ludicrous, I know, but at the present moment I am conscious of a deep and personal hatred against the man which I would give a good deal to satisfy. I knew he thought me a liar but I did not know that he suspected me of being anything much worse. But ’tis an unsavoury subject and a most unsavoury man. Let us drop him off the penpoint and burn incense to cleanse the room.

This letter rages with disgust and revulsion, and I believe it expresses Kipling’s true and lasting attitude.

It is hard to construct a timeline of the progress of the friendship between Rudyard and Wolcott. It is not even certain when and where they first met.

Kipling arrived in England on 5 October 1889. On 18 March 1890 Carrie (whose turn it was to keep house for Wolcott) wrote to Josephine telling how she had introduced Rudyard to typewriting

(Lycett).

But early in June 1890 Arthur Waugh (Wolcott’s secretary) was sent round to Kipling to try to arrange an American edition of The Book of the Forty-five Mornings, which was eventually judged not worthy to be published. Only “Bertran and Bimi” and “Moti Guj – Mutineer” survived to be collected in Life’s Handicap. Kipling’s comment was:

Extraordinarily importunate person, this Mr. Balestier. Tell him to enquire again in six months. (Waugh, One Man’s Road, Chapman & Hall, 1935)

Yet barely a month later (12 July 1890) Wolcott wrote to his friend William Dean Howells:

Lately I have been seeing even more of Kipling with whom I am writing a story in collaboration.

This was The Naulahka.

This is certainly evidence of Wolcott’s appeal, the only time Kipling ever collaborated, apart from “Echoes”, a little book of parodies written with his sister Trix in India in 1884. He always gives the impression of a craftsman with such high standards of workmanship and such an individual technique that it would be very difficult for anyone to work with him. As late as 1923 his rectorial address to St. Andrew’s University was titled “Independence” and dwelt on the necessity of “owning oneself”. Wolcott on the other hand, with three unsuccessful novels behind him, knew he needed help. According to Seymour-Smith, he had previously asked Mrs Humphry Ward if he might write a novel with her: ‘She rejected the proposal outright.’

Harry Ricketts comments (p. 179):

Quite apart from his personal charm, Wolcott appealed to Kipling in various ways: as

a confidant, with that role vacant in the absence of Trix, cousin Margaret and Mrs Hill; as an American, capable of sharing Kipling’s own sense of ‘foreignness’; as someone intimate with the English literary scene, yet not constrained by its archaic gentility; and as a doer, above all revealed

through his campaign against the American publishing pirates.

This was indeed a powerful attraction for Kipling: Wolcott could help to get American copyright for his work. In fact this was one of the reasons why he had come to England – so that his company could offer to publish authorised editions of English books in America to secure copyright there. At the time American publishers were not bound by international copyright agreements. However, their friendship was well-established before he began to help Kipling in this way.

Kipling had been infuriated by the way American publishers produced unauthorised editions of his writings and paid him nothing for them, or in the case of Harper’s, ten pounds, which Kipling rejected as ‘the wages of one New York road scavenger for one month’.

He wrote a letter of protest, which was published in The Athenaeum on 4 October 1890. After failing to secure the support of three leading writers, he denounced them in a furious poem “The Rhyme of the Three Captains.

Kipling completed his novel The Light that Failed in August 1890. He was still working on it when he started the collaboration on The Naulahka. Wolcott arranged for his company Lovell to publish it in America in November. In England, it appeared in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. In January 1891 Wolcott secured English copyright by issuing a few copies bound in book form. Both these versions had a happy ending, where Maisie relents and marries Dick. There is some evidence that both Wolcott and Kipling’s mother Alice recommended this change. (See the article by David Alan Richards, Kipling’s most recent bibliographer, on the various magazine versions of the novel.

In March 1891 MacMillan’s published the English book form, the longer tragic version that we know today, with the brief Preface ‘This is the story of The Light That Failed as it was originally conceived by the Writer.’ This suggests that the “happy” version was produced against his better artistic judgement.

In November 1890 Wolcott arranged for Lovell to publish an authorised American edition of Barrack-Room Ballads. Wolcott also arranged the publication of a book of Kipling’s short stories, “Mine Own People” in the USA in Spring 1891. The English edition, with the title changed to Life’s Handicap, came out in August.

During this time the courtship between Carrie and Rudyard was progressing. Seymour-Smith writes ‘he became engaged to Caroline in about May 1891 , apparently relying on the 1945 biography by Hilton Brown . Carrington writes:

Before The Naulahka began to appear in print, (in instalments in The Century Magazine from November 1891) there was an understanding between Rudyard and Wolcott’s sister Caroline.’

Notwithstanding, Kipling set off in August 1891 on a voyage to the Cape, New Zealand and Australia. He had hoped to go on and visit R. L. Stevenson in Samoa, but the captain of a boat which might or might not go there was “too devotedly drunk”. So he headed back to India and his parents in Lahore.

There, around Christmas, he got a telegram from Carrie saying “WOLCOTT DEAD STOP COME BACK TO ME STOP. He was back in London on 10 January 1892, and on 18th he and Carrie were married.

The Naulahka was still appearing in instalments in The Century Magazine. Kipling wrote the last few pages while crossing the Atlantic on SS Teutonic on his honeymoon. Barrack-Room Ballads was published by Methuen in England in March 1892.

There is no mention of Wolcott in Something of Myself.

[P.H.]

©Philip Holberton 2011 All rights reserved