Background

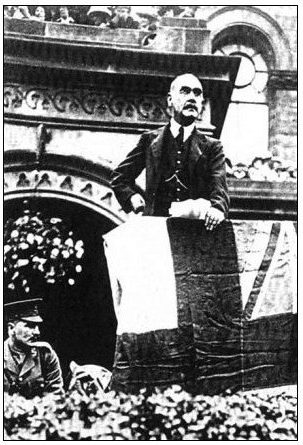

The circumstances of this speech have been described by B. S. Townroe in an article in the Kipling Journal, December 1946. Townroe, as assistant to Lord Derby in his recruiting campaign in Lancashire, suggested that they incite Kipling to address an open-air meeting to stimulate a “very sluggish” recruiting at Southport. To their surprise, Kipling at once accepted. The speech he made “through loud-speakers to thousands of people gathered together in Lord Street and the gardens below” was, according to Townroe, “the most powerful attack on German methods that had been made, and it was cabled to all parts of the world. It had an immense Press at the time”.

Kipling himself said later that “I tried once in a speech to point out that the German game was to bring the conquered to such a condition that they would not be able to look at each other afterwards: but that was too general to be understood” (Thomas Pinney (Ed.) Letters vol 4 p. 420).

[T.P.]

Ladies and Gentlemen, I am here to speak on behalf of a system in which I do not believe, and in which, I daresay, a good many of you do not believe either—the system of voluntary service. It seems to me unfair and unbusinesslike that after ten months of war we should still be compelled to raise men by the same methods as we raise money at a charity bazaar; but clumsy and unfair as that system is, it is the only one we have, and we must work it. (Hear, hear.) We committed ourselves to it in time of peace when we decided that we would not endure national service on any terms whatever. We chose it because it made us more comfortable and because it released us from obligations which might have cut into our pleasure, and our money. We believed that in the hour of danger there would always be enough men who would of their own free will defend their country. That belief was justified in the past. The mistake we have made—and it was not for lack of being warned—was that we did not conceive we should ever wage such a war as the war that we are waging now. The system by which we are meeting that war is grossly unfair, but since we chose it of deliberate intent, in the face of grave warnings, we cannot now that it is being tested, shelter ourselves behind its defects. (Hear, hear.) How does the situation stand with regard to the recruiting to-day? There is, of course, a small and pernicious minority (incorrectly transcribed as ‘majority’ in some printed versions), which does not intend to inconvenience itself for any consideration whatever, but I am convinced that the overwhelming number of men who have not yet come forward to enlist argue, “Why should I go when my neighbour stays behind? Make it fair all round, and I will go gladly.” That is a detail that should have been attended to in time of peace. It is too late; it is illogical to complain of it now. If it is changed, so much the better, but meantime we must reap what we have sown. (Hear, hear.)

The German has spent quite as much energy in the last forty-five years preparing for war as we have in convincing ourselves that war should not be prepared for. He started this war with a magnificent equipment that gave him time and heavy taxation to get together. That equipment we have had to face for the last ten months. We have had to face more. The German went into this war with a mind which had been carefully trained out of the idea of every moral sense of obligation—private, public, and international. He does not recognise the existence of any law, least of all those to which he has subscribed to himself, in waging war against combatants or non-combatants, men, women, and children. He has done from his own point of view very well indeed. All mankind bears witness to-day that there is no crime, no cruelty, no abomination that the mind of man can conceive which the German has not perpetrated, is not perpetrating, and will not perpetrate if he is allowed to go on. These horrors and perversions were not invented by him on the spur of the moment. They were arranged beforehand, their outlines are laid down in the German war-book. They are part of the system in which Germany has been scientifically educated. It is the essence of that system to make a hell of the countries where the German armies may set foot, that any terms Germany may offer will seem like heaven to the inhabitants whose bodies she has defiled and whose minds she has broken of set purpose and intention.

In the face of these facts, it would be folly for any fit man to talk for a minute of what he would do if our system of recruiting were changed, or to hang on, as some men hang on, in the hope of compulsion being introduced. We shall not be saved by argument. (Hear, hear.) We shall not be saved by hanging on to our private jobs and businesses. Our own strength and will alone can save us. If these fail, the alternative is robbery, rape of the women, and starvation as a prelude to slavery. Nor need we expect any miracle to save us. So long as an unbroken Germany exists, just so long life on this planet will be intolerable, not only for us and our Allies, but for all humanity. And humanity knows it.

At present six European nations are bearing the burden of the war. There is a fringe of shivering neutrals almost under the German guns who can look out of their front doors and see, as they were meant to see, what has been done to Belgium, the German-guaranteed neutral Belgium. But however the world pretends to divide itself, there are only two divisions in the world to-day—human beings and Germans. (Laughter and applause.) And the German knows it. Human beings have long ago sickened of him and everything connected with him, with all he does, says, thinks, or believes. From the ends of the earth human beings desire nothing more keenly than that this unclean monster should be thrust out from membership and the memory of the nations of the earth. (Applause.) The German’s answer to the world’s loathing is this. He says: “I am strong. I kill. I purpose to go on killing by all means in my power till I have imposed my wall on all human beings.” He gives no choice. He leaves no middle way. He had reduced civilisation and all that civilisation means to the simple question of kill or be killed. Up to the present, as far as we can find out, Germany has suffered three million casualties. She can endure another three millions, and, for aught we know, another three millions at the back of that. We have no reason to expect that she will break up suddenly and dramatically, as some people still believe. Why should she? She took two generations to prepare herself in every detail, and through every fibre of her national being for this war. She is playing for the highest stakes in the world—for the dominion of the world. It seems to me that she must either win or bleed to death almost where her lines run to-day. Therefore, we and our Allies must continue to pass our children through the fire to Moloch until Moloch perish, that, as I see it, is where we stand, and where Germany stands. (Applause.)

Turn your mind for a moment to the idea of a conquering Germany. You need not go far to see what it would mean for us. In Belgium at this hour, several million Belgians are making war material or fortification for their conquerors. They are given enough food to support life as the German thinks it ought to be supported. And, by the way, I believe the United States of America supplies the greater part of that food. In return they are compelled to work at the point of the bayonet. If they object they are shot. Their factories, their public institutions, their private houses, have long ago been gutted, and everything in them that was useful or valuable has been packed up and sent into Germany. They have no more property, and no more rights than cattle; and they dare not lift up a hand to protect the honour of their women folk. And less than a year ago they were among the most prosperous and the most civilised of the nations of the earth. There has been nothing like the horror of their fate in all history, and that system is in full working order within fifty miles of the English coast. (Hear, hear.) Where I live I can hear the guns that are trying to extend it. The same system as exists in Belgium, exists in such parts of France and Poland as are in German hands. But whatever has been dealt out to Belgium, France, or Poland will be England’s fate ten-fold if we fail to subdue the Germans. (Applause.) That we shall be broken, that we shall he plundered, that we shall he enslaved will only be the first part of the matter.

There are special reasons in the German mind why we should he morally and mentally shamed and dishonoured beyond any other people—why we should he degraded till those who survive can scarcely look each other in the face. Be perfectly sure that if Germany is victorious, even refinement of outrage which is in the compass of the German imagination will be inflicted upon us in every aspect of our lives. Over and above all this, no pledge we can offer, no guarantee that we can give will he accepted by Germany as binding. Why, she has broken her own most solemn oaths and obligations, and by the very fact of her existence she is bound to trust nothing and to recognise nothing except immediate superior force hacked by illimitable cruelty. So you see there can be no terms. (Hear, hear.) Realise, too, that if the Allies are beaten, there will be no spot on the globe where a soul can escape from the domination of this enemy of mankind. There has been childish talk that the Western hemisphere would always offer a refuge from oppression. Put that thought from your mind. If the Allies are beaten, Germany would not need to send a single battleship across the Atlantic. She would send an order, and it would be obeyed. Civilisation would be bankrupt, and the western world would be taken over with the rest of the wreckage by Germany, the receiver. So you see there is no retreat possible. There are no terms, there is no retreat in this war. It must go forward, and with those men of England who are eligible for service, but who have not yet offered themselves, the decision of the war rests. (Loud applause.)

Let us look at a few figures. Like yourselves, I have no special information; but, as far as one can estimate, rather more than 2,000,000 men have joined the services up to date. This is an impressive record till you remember that the total population of these islands is about 45,000,000, so that the proportion works out at about 5 per cent, of the total population, and 10 per cent, of the total male population. We do not know how many soldiers we shall need to end this war, but we do know that we do not need 90 per cent of the total male population to make ammunition and carry on the ordinary business of the country. (Applause.) People who won’t look facts in the face sometimes say, “What’s the sense of piling in men when you have not the arms and equipment for them?” The answer is perfectly simple. You can use equipment the minute you get it, but you cannot use a man the minute you get him. (Applause.) He has to be trained. That is why the supply of men has always got to be months ahead of other supplies. And we need a steady, unbroken flow of young men—young and without domestic ties for choice—coming on and on into training. Once again I will admit as freely as anyone here the immense unfairness of our system of recruiting, which has been well called quite rightly conscription by cajolery; but it is the system we have chosen, and till we have another we must work it. Those who believe in national service can take comfort from the thought that if the Government won’t bring it in, they must be quicker than the Government—it is not difficult to be quicker than the Government—(laughter)—and bring themselves in. (Hear, hear.) Those who believe in the principles of voluntary service must now realize that now is the one time for them to show what an excellent system it is by voluntarily shouldering their obligations. (Applause.)

In the meantime, public opinion is hardening against the eligible men who have excuses which are not reasons for not enlisting. Public opinion is hardening against those parents, the wives, and the relatives of those men and employers of those men, who, directly or indirectly, are keeping these men back. You cannot expect people who have given or lost their own flesh and blood in this war to be patient or sympathetic with people whose husbands are untouched or unseparated. The feeling may or may not be reasonable, but it is one of the results of our system, and as more men join that feeling will increase. What’s the sense of waiting until it breaks bounds? No words can begin to do justice to the bravery and the devotion of those of our men who have already gone up against Germany. (Applause.) They have dealt almost as a matter of routine, with battles, any one of which in the old days would have made the marvel and the glory of a generation. (Loud applause.) They have endured, as never troops were called upon to endure, the most amazing devices of war, and the unclean malice of the enemy. They have shown themselves through all these things heroes without stain. (Loud applause.) The counties know, the big cities know, and the little villages where they mark the names on the church door know, what their neighbours and their kin have done. There is no part of the land to-day that has not its new pride and its new reverence in the achievements of our Armies, and no part of the land has a better right to this pride than Lancashire. (Applause.) But the need—the Empire’s great need—is for more men of the same mould. In the old days—days that seem now so small and so far off—the days when we dealt in words, there used to be a saving which ran: “What Lancashire thinks to-day, England will think to-morrow.” (Applause.) Let us change that saying for three years, or for the duration of the war, to “What Lancashire does to-day, England will do to-morrow.” (Loud applause.)

—Southport Guardian, 23 June 1915.