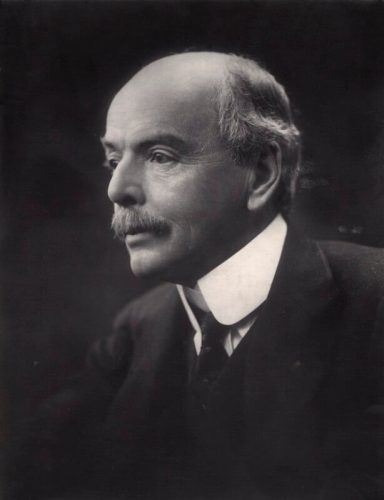

Sir Leander Starr Jameson, 1st Bt by George Charles Beresford • platinum print, 8 October 1913 NPG x18842 © National Portrait Gallery, London • NPG

(1896)

(notes by Philip Holberton)

Publication

The poem was first published in The Book of Beauty in November 1896. In the second edition of that work in 1902 it was replaced by a different poem, Blue Roses. It is listed in ORG as no 694. It should not be confused with the earlier poem also called ‘The Quest’.

Collected in:

- Inclusive Verse (1919)

- Definitive Verse (1940)

- The Sussex Edition vol xxxv (1939)

- The Burwash Edition vols xxviii (1941)

- Cambridge Edition (2013) Ed. Pinney, p. 814

The poem

This poem tells of a knight who has been defeated in battle. Nevertheless, he is confident that he has weakened the enemy and this weakness will show up when the war is resumed. It has the ring of the poems that Kipling wrote for a special purpose or to mark a special occasion. But, as John Radcliffe points out:

The Book of Beauty was a curious publication for such a poem to figure in, Since the book – which sounds like one for the coffee-table – had a private circulation of just a few hundred, in Britain and the United States, it cannot have made much impact.

Sometimes Kipling put in a subtitle to explain the occasion (e,g. his poem “Cleared” has the subtitle In memory of the Parnell Commission) but he did not do so for “The Quest”.

This Editor suggests that the poem commemorates the ill-starred Jameson Raid, which had ended ignominiously in January 1896. Dr. Leander Starr Jameson, a close associate of Cecil Rhodes, had invaded the Transvaal with 500 men, hoping to trigger an uprising by the Uitlanders (foreigners to the Boers), the mainly British immigrants who had come to develop and exploit the goldfields.

The rising did not take place and the Raid ended in surrender on 2 January 1896. The Transvaal Government sent Jameson back to England as a prisoner to face trial; he was convicted of violating the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1870 and sentenced to fifteen months’ imprisonment. The Raid could be likened to a Quest, and although it was a disaster it clearly did not shake Kipling’s faith in Cecil Rhodes’ dream of making all of Southern Africa part of the Empire and he may have anticipated a second attempt to gain the Transvaal for England. John Radcliffe agrees:

The circumstances – the valiant soldier bloodied but unbowed – seem close, and of course, for reasons few have since been able to fathom, Kipling was greatly impressed by Jameson, who was the model for his best-known and most-loved poem `If–‘:

We have Kipling’s word for this:

Among the verses in Rewards was one set called `If–‘, which escaped from the book, and for a while ran about the world. They were drawn from Jameson’s character. [Something of Myself p. 146]

Rewards and Fairies was published in 1910, so Kipling’s admiration for Jameson persisted long after the fiasco of the Raid. However, he seems to have blotted out ‘The Quest’ from his memory, perhaps it had been quickly written and quickly forgotten. He wrote to E. L. White on 8 April 1913:

I haven’t your copy of the Quest – but if it begins ‘The knight came home from the quest’ – I wrote it. I forget when or why and I don’t think it was published anywhere. Probably I wrote it for somebody. It ain’t any allegory. [Pinney, Lettters, vol.4]

Notes on the Text

[Verse 1]

my horse to be shot!: his horse has been so badly injured that the

kindest thing is to shoot it, to put it out of its pain. The ORG editors have speculated that ‘shot’ might have been a misprint for ‘shod’, although it does not rhyme so well. It seems unlikely that wounded horses would have been shot in the days of lances and bows and arrows. However, the word is ‘shot’ in The Book of Beauty and all subsequent collections.

Daniel Hadas quotes Pinney on the point: “The word ‘shot’ in lines 10 and 38 in all editions is possibly a variant spelling of ‘shod’, though I find no such form recorded”.

I too think “shod” must be the sense, not just because of the anachronism (which could maybe be justified by the mix of swords, spears, and guns in ‘The Fairies’ Siege’), but because shoeing the horse matches mending the lance in the line before, whereas shooting the horse introduces a grim note that feels discordant. OED doesn’t give “shot” as a form of “shoe”, but making up / misremembering an archaic form seems like something Kipling could easily do. [D.H.]

Haro!: an expression of distress: alas!

[Verse 2]

their van: their vanguard, the front ranks of the enemy army.

I could not miss my man: the enemy were so close together that he was sure to hit someone with his lance.

I could not carry by: he could not break through the enemy ranks.

[Verse 3]

Ye have not seen my foe/ Ye have not told his slain: See “Boxing” from “An Almanac of Twelve Sports”:

Man cannot tell, but Allah knows

How much the other side was hurt.

good handsel: a ‘handsel’ is something unwholesome or unwelcome, given or received; ironic here. [see OED]

[P.H]

©Philip Holberton 2017 All rights reserved