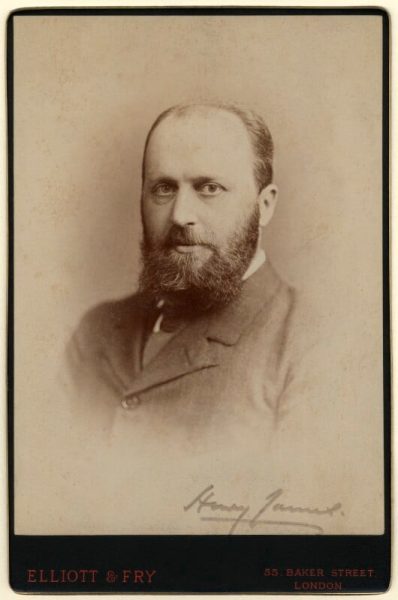

Henry James by Elliott & Fry • albumen cabinet card, November 1884 NPG x126742 © National Portrait Gallery, London • NPG

Introduction by Henry James

Introduction by the celebrated novelist to an edition of

‘Mine Own People’ published in New York in March 1891.

This included the stories collected later that year as ‘Life’s Handicap’

James wrote to his brother William on 6 February 1892,

that ‘Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete

man of genius (as distinct from fine intelligence) that

I have ever known’.

It would be difficult to answer the general question whether

the books of the world grow, as they multiply, as much better as

one might suppose they ought, with such a lesson on wasteful

experiment spread perpetually behind them. There is no doubt,

however, that in one direction we profit largely by this education:

whether or no we have become wiser to fashion, we have certainly

become keener to enjoy. We have acquired the sense of a particular

quality which is precious beyond all others—so precious as to

make us wonder where, at such a rate, our posterity will look

for it, and how they will pay for it.

After tasting many essences we find freshness the sweetest of all.

We yearn for it, we watch for it and lie in wait for it, and when we

catch it on the wing (it flits by so fast), we celebrate our capture

with extravagance. We feel that after so much has come and gone

it is more and more of a feat and a tour deforce to be fresh. The

tormenting part of the phenomenon is that, in any particular key,

it can happen but once—by a sad failure of the law that inculcates

the repetition of goodness. It is terribly a matter of accident;

emulation and imitation have a fatal effect upon it. It is easy

to see, therefore, what importance the epicure may attach to the

brief moment of its bloom. While that lasts we all are epicures.

This helps to explain, I think, the unmistakable intensity of the gen-

eral relish for Mr. Rudyard Kipling. His bloom lasts, from month to

month, almost surprisingly—by which I mean that he has not worn out

even by active exercise the particular property that made us all, more

than a year ago, so precipitately drop everything else to attend to him.

He has many others which he will doubtless always keep; but a part

of the potency attaching to his freshness, what makes it as exciting as a

drawing of lots, is our instinctive conviction that he cannot, in the

nature of things, keep that; so that our enjoyment of him, so long as

the miracle is still wrought, has both the charm of confidence and the

charm of suspense. And then there is the further charm, with Mr.

Kipling, that this same freshness is such a very strange affair of its

kind—so mixed and various and cynical, and, in certain lights, so

contradictory of itself. The extreme recentness of his inspiration is as

enviable as the tale is startling that his productions tell of his being at

home, domesticated and initiated, in this wicked and weary world.

At times he strikes us as shockingly precocious, at others as serenely

wise. On the whole, he presents himself as a strangely clever youth

who has stolen the formidable mask of maturity and rushes about

making people jump with the deep sounds, the sportive exaggerations

of tone, that issue from its painted lips. He has this mark of a real

vocation, that different spectators may like him—must like him, I

should almost say—for different things: and this refinement of attrac-

tion, that to those who reflect even upon their pleasures he has as much

to say as to those who never reflect upon anything. Indeed there is a

certain amount of room for surprise in the fact that, being so much the

sort of figure that the hardened critic likes to meet, he should also

be the sort of figure that inspires the multitude with confidence—for a

complicated air is, in general, the last thing that does this.

By the critic who likes to meet such a bristling adventurer as Mr.

Kipling I mean of course the critic for whom the happy accident of

character, whatever form it may take, is more of a bribe to interest than

the promise of some character cherished in theory—the appearance of

justifying some foregone conclusion as to what a writer or a book

‘ought’, in the Ruskinian sense, to be: the critic in a word, who has,

a priori, no rule for a literary production but that it shall have genuine

life. Such a critic (he gets much more out of his opportunities, I think,

than the other sort) likes a writer exactly in proportion as he is a

challenge, an appeal to interpretation, intelligence, ingenuity, to what

is elastic in the critical mind—in proportion indeed as he may be a

negation of things familiar and taken for granted. He feels in this

case how much more play and sensation there is for himself.

Mr. Kipling, then, has the character that furnishes plenty of play and

of vicarious experience—that makes any perceptive reader foresee

a rare luxury. He has the great merit of being a compact and convenient

illustration of the surest source of interest in any painter of life—that

of having an identity as marked as a window-frame. He is one of the

illustrations, taken near at hand, that help to clear up the vexed question,

in the novel or the tale, of kinds, camps, schools, distinctions, the right

way and the wrong way; so very positively does he contribute to the

showing that there are just as many kinds, as many ways, as many

forms and degrees of the ‘right’, as there are personal points of view.

It is the blessing of the art he practises that it is made up of experience

conditioned, infinitely, in this personal way—the sum of the feeling

of life as reproduced by innumerable natures; natures that feel through

all their differences, testify through their diversities. These differences,

which make the identity, are of the individual; they form the channel

by which life flows through him, and how much he is able to give us

of life—in other words, how much he appeals to us—depends on

whether they form it solidly.

This hardness of the conduit, cemented with a rare assurance, is

perhaps the most striking idiosyncrasy of Mr. Kipling; and what makes

it more remarkable is that accident of his extreme youth which, if we

talk about him at all, we cannot affect to ignore. I cannot pretend to

give a biography or a chronology of the author of Soldiers Three, but

I cannot overlook the general, the importunate fact that, confidently

as he has caught the trick and habit of this sophisticated world, he

has not been long of it. His extreme youth is indeed what I may call

his window-bar—the support on which he somewhat rowdily leans

while he looks down at the human scene with his pipe in his teeth;

just as his other conditions (to mention only some of them), are his

prodigious facility, which is only less remarkable than his stiff selec-

tion; his unabashed temperament, his flexible talent, his smoking-room

manner, his familiar friendship with India—established so rapidly, and

so completely under his control; his delight in battle, his ‘cheek’ about

women—and indeed about men and about everything; his determina-

tion not to be duped, his ‘imperial’ fibre, his love of the inside view,

the private soldier and the primitive man. I must add further to this

list of attractions the remarkable way in which he makes us aware that

he has been put up to the whole thing directly by life (miraculously,

in his teens), and not by the communications of others. These elements,

and many more, constitute a singularly robust little literary character

(our use of the diminutive is altogether a note of endearment and en-

joyment), which, if it has the rattle of high spirits and is in no degree

apologetic or shrinking, yet offers a very liberal pledge in the way

of good faith and immediate performance. Mr. Kipling’s performance

comes off before the more circumspect have time to decide whether

they like him or not, and if you have seen it once you will be sure to

return to the show. He makes us prick up our ears to the good news

that in the smoking-room too there may be artists; and indeed to an

intimation still more refined—that the latest development of the

modern also may be, most successfully, for the canny artist to put his

victim off the guard by imitating the amateur (superficially, of course)

to the life.

These, then, are some of the reasons why Mr. Kipling may be dear

to the analyst as well as, M. Renan says, to the simple. The simple

may like him because he is wonderful about India, and India has not

been ‘done’; while there is plenty left for the morbid reader in the

surprise of his skill and the Jioriture of his form, which are so oddly

independent of any distinctively literary note in him, any bookish

association. It is as one of the morbid that the writer of these remarks

(which doubtless only too shamefully betray his character) exposes

himself as most consentingly under the spell. The freshness arising

from a subject that—by a good fortune I do not mean to under-

estimate—has never been ‘done’, is after all less of an affair to build

upon than the freshness residing in the temper of the artist. Happy

indeed is Mr. Kipling, who can command so much of both kinds.

It is still as one of the morbid, no doubt—that is, as one of those who

are capable of sitting up all night for a new impression of talent, of

scouring the trodden field for one little spot of green—that I find our

young author quite most curious in his air, and not only in his air but

in his evidently very real sense, of knowing his way about life. Curious

in the highest degree and well worth attention is such an idiosyncrasy

as this in a young Anglo-Saxon. We meet it with familiar frequency

in the budding talents of France, and it startles and haunts us for an

hour. After an hour, however, the mystery is apt to fade, for we find

that the wondrous initiation is not in the least general, is only ex-

ceedingly special, and is, even with this limitation, very often rather

conventional. In a word, it is with the ladies that the young Frenchman

takes his ease, and more particularly with ladies selected expressly

to make this attitude convincing.

When they have let him off, the dimnesses too often encompass him.

But for Mr. Kipling there are no dimnesses anywhere, and if the ladies

are indeed violently distinct they are only strong notes in a

universal loudness. This loudness fills the ears of Mr. Kipling’s

admirers (it lacks sweetness, no doubt, for those who are not of

the number), and there is really only one strain that is absent from

it—the voice, as it were, of the civilised man; in whom I of course

also include the civilised woman. But this is an element that

for the present one does not miss—every other note is so articulate

and direct.

It is a part of the satisfaction the author gives us that he can make us

speculate as to whether he will be able to complete his picture alto-

gether (this is as far as we presume to go in meddling with the question

of his future) without bringing in the complicated soul. On the day

he does so, if he handles it with anything like the cleverness he has

already shown, the expectation of his friends will take a great bound.

Meanwhile, at any rate, we have Mulvaney, and Mulvaney is after all

tolerably complicated. He is only a six-foot saturated Irish private, but

he is a considerable pledge of more to come. Hasn’t he, for that matter,

the tongue of a hoarse syren, and hasn’t he also mysteries and infini-

tudes almost Carlylese? Since I am speaking of him I may as well say

that, as an evocation, he has probably led captive those of Mr. Kipling’s

readers who have most given up resistance. He is a piece of portraiture

of the largest, vividest kind, growing and growing on the painter’s

hands without ever outgrowing them. I can’t help regarding him, in

a certain sense, as Mr. Kipling’s tutelary deity—a landmark in the

direction in which it is open to him to look furthest. If the author will

only go as far in this direction as Mulvaney is capable of taking him

(and the inimitable Irishman is, like Voltaire’s Habakkuk, capable de

tout), he may still discover a treasure and find a reward for the services

he has rendered the winner of Dinah Shadd. I hasten to add that the

truly appreciative reader should surely have no quarrel with the

primitive element in Mr. Kipling’s subject-matter, or with what, for

want of a better name, I may call Inis love of low life. What is that

but essentially a part of his freshness? And for what part of his fresh-

ness are we exactly more thankful than for just this smart jostle that he

gives the old stupid superstition that the amiability of a storyteller

is the amiability of the people he represents—that their vulgarity, or

depravity, or gentility, or fatuity are tantamount to the same qualities

in the painter himself? A blow from which, apparently, it will not

easily recover is dealt this infantine philosophy by Mr. Howells when,

with the most distinguished dexterity and all the detachment of a

master, he handles some of the clumsiest, crudest, most human things

in life—answering surely thereby the playgoers in the sixpenny gallery

who howl at the representative of the villain when he comes before

the curtain.

Nothing is more refreshing than this active, disinterested sense of the

real; it is doubtless the quality for the want of more of which our

English and American fiction has turned so woefully stale. We are

ridden by the old conventionalities of type and small proprietries of

observance—by the foolish baby-formula (to put it sketchily) of the

picture and the subject. Mr. Kipling has all the air of being disposed to

lift the whole business off the nursery carpet, and of being perhaps

even more affable than he is disposed. One must hasten of course to

parenthesise that there is not, intrinsically, a bit more luminosity in

treating of low life and of primitive man than of those whom civi-

lisation has kneaded to a finer paste: the only luminosity in either case

is in the intelligence with which the thing is done. But it so happens

that, among ourselves, the frank, capable outlook, when turned upon

the vulgar majority, the coarse, receding edges of the social perspective,

borrows a charm from being new; such a charm as, for instance,

repetition has already despoiled it of among the French—the hapless

French who pay the penalty as well as enjoy the glow of living in-

tellectually so much faster than we. It is the most inexorable part of

our fate that we grow tired of everything, and of course in due time we

may grow tired even of what explorers shall come back to tell us about

the great grimy condition, or with unprecedented items and details,

about the grey middle state which darkens into it. But the explorers,

bless them! may have a long day before that; it is early to trouble about

reactions, so that we must give them the benefit of every presumption.

We are thankful for any boldness and any sharp curiosity, and that is

why we are thankful for Mr. Kipling’s general spirit and for most of

his excursions.

Many of these, certainly, are into a region not to be designated as

superficially dim, though indeed the author always reminds us that

India is above all the land of mystery. A large part of his high spirits,

and of ours, comes doubtless from the amusement of such vivid,

heterogeneous material, from the irresistible magic of scorching suns,

subject empires, uncanny religions, uneasy garrisons and smothered-up

women—from heat and colour and danger and dust. India is a portentous

image, and we are duly awed by the familiarities it undergoes

at Mr. Kipling’s hands and by the fine impunity, the sort of fortune

that favours the brave, of his want of awe. An abject humility is not

his strong point, but he gives us something instead of it—vividness and

drollery, the vision and the thrill of many things, the misery and

strangeness of most, the personal sense of a hundred queer contacts

and risks. And then in the absence of respect he has plenty of knowledge,

and if knowledge should fail him he would have plenty of invention.

Moreover, if invention should ever fail him, he would still have the

lyric string and the patriotic chord, on which he plays admirably;

so that it may be said he is a man of resources. What he gives us, above

all, is the feeling of the English manner and the English blood in

conditions they have made at once so much and so little their own;

with manifestations grotesque enough in some of his satiric sketches and

deeply impressive in some of his anecdotes of individual responsibility.

His Indian impressions divide themselves into three groups, one of

which, I think, very much outshines the others. First to be mentioned

are the tales of native life, curious glimpses of custom and super-

stition, dusky matters not beholden of the many, for which the author

has a remarkable flair. Then comes the social, the Anglo-Indian episode,

the study of administration and military types and of the wonderful

rattling, riding ladies who, at Simla and more desperate stations, look

out for husbands and lovers; often, it would seem, the husbands and

lovers of others. The most brilliant group is devoted wholly to the

common soldier, and of this series it appears to me that too much good

is hardly to be said. Here Mr. Kipling, with all his offhandness, is a

master; for we are held not so much by the greater or less oddity of

the particular yarn—sometimes it is scarcely a yarn at all, but something

much less artificial—as by the robust attitude of the narrator, who never

arranges or glosses or falsifies, but makes straight for the common and

the characteristic. I have mentioned the great esteem in which I hold

Mulvaney—surely a charming man and one qualified to adorn a

higher sphere. Mulvaney is a creation to be proud of, and his two

comrades stand as firm on their legs. In spite of Mulvaney’s social

possibilities they are all three finished brutes; but it is precisely in the

finish that we delight. Whatever Mr. Kipling may relate about them

for ever will encounter readers equally fascinated and unable fully to

justify their faith.

Are not those literary pleasures after all the most intense which are

the most perverse and whimsical, and even indefensible? There is a

logic in them somewhere, but it often lies below the plummet of

criticism. The spell may be weak in a writer who has every reasonable

and regular claim, and it may be irresistible in one who presents him-

self with a style corresponding to a bad hat. A good hat is better than

a bad one, but a conjurer may wear either. Many a reader will never be

able to say what secret human force lays its hand upon him when

Private Ortheris, having sworn ‘quietly into the blue sky’, goes mad

with home-sickness by the yellow river and raves for the basest sights

and sounds of London. I can scarcely tell why I think ‘The Courting of

Dinah Shadd’ a masterpiece (though, indeed, I can make a shrewd

guess at one of the reasons), nor would it be worth while perhaps to

attempt to defend the same pretension in regard to ‘On Greenhow

Hill’—much less to trouble the tolerant reader of these remarks with

a statement of how many more performances in the nature of ‘The

End of the Passage’ (quite admitting even that they might not rep-

resent Mr. Kipling at his best), I am conscious of a latent relish for.

One might as well admit while one is about it that one has wept

profusely over ‘The Drums of the Fore and Aft’, the history of the

‘Dutch courage’ of two dreadful dirty little boys, who, in the face of

Afghans scarcely more dreadful, saved the reputation of their regiment

and perished, the least mawkishly in the world, in a squalor of battle

incomparably expressed. People who know how peaceful they are

themselves and have no bloodshed to reproach themselves with

needn’t scruple to mention the glamour that Mr. Kipling’s intense

militarism has for them and how astonishingly contagious they find

it, in spite of the unromantic complexion of it—the way it bristles with

all sorts of uglinesses and technicalities. Perhaps that is why I go all the

way even with The Gadsbys—the Gadsbys were so connected (un-

comfortably it is true) with the Army. There is fearful fighting—or a

fearful danger of it—in ‘The Man who would be King’: is that the

reason we are deeply affected by this extraordinary tale? It is one of

them, doubtless, for Mr. Kipling has many reasons, after all, on his

side, though they don’t equally call aloud to be uttered.

One more of them, at any rate, I must add to these unsystematised

remarks—it is the one I spoke of a shrewd guess at in alluding to

‘The Courting of Dinah Shadd’. The talent that produces such a tale

is a talent eminently in harmony with the short story, and the short

story is, on our side of the Channel and of the Atlantic, a mine which

will take a great deal of working. Admirable is the clearness with which

Mr. Kipling perceives this—perceives what innumerable chances it

gives, chances of touching life in a thousand different places, taking it

up in innumerable pieces, each a specimen and an illustration. In a

word, he appreciates the episode, and there are signs to show that this

shrewdness will, in general, have long innings. It will find the detach-

able, compressible ‘case’ an admirable, flexible form; the cultivation

of which may well add to the mistrust already entertained by Mr.

Kipling, if his manner does not betray him, for what is clumsy and

tasteless in the time-honoured practice of the ‘plot’. It will fortify him

in the conviction that the vivid picture has a greater communicative

value than the Chinese puzzle. There is little enough plot in such a

perfect little piece of hard representation as ‘The End of the Passage’,

to cite again only the most salient of twenty examples.

But I am speaking of our author’s future, which is the luxury that

I meant to forbid myself—precisely because the subject is so tempting.

There is nothing in the world (for the prophet) so charming as to

prophesy, and as there is nothing so inconclusive the tendency should

be repressed in proportion as the opportunity is good. There is a

certain want of courtesy to a peculiarly contemporaneous present even

in speculating, with a dozen deferential precautions, on the question

of what will become in the later hours of the day of a talent that has

got up so early. Mr. Kipling’s actual performance is like a tremendous

walk before breakfast, making one welcome the idea of the meal, but

consider with some alarm the hours still to be traversed. Yet if his

breakfast is all to come the indications are that he will be more active

than ever after he has had it. Among these indications are the un-

flagging character of his pace and the excellent form, as they say in

athletic circles, in which he gets over the ground. We don’t detect

him stumbling; on the contrary, he steps out quite as briskly as at first

and still more firmly. There is something zealous and craftsman-like

in him which shows that he feels both joy and responsibility. A whim-

sical, wanton reader, haunted by a recollection of all the good things he

has seen spoiled; by a sense of the miserable, or, at any rate, the inferior,

in so many continuations and endings, is almost capable of perverting

poetic justice to the idea that it would be even positively well for so

surprising a producer to remain simply the fortunate, suggestive, un-

confirmed and unqualified representative of what he has actually done.

We can always refer to that.

![]()