THE MOST IMPORTANT thing about Tegumai Bopsulai and his dear daughter, Taffimai Metallumai, were the Tabus of Tegumai, which were all Bopsulai.

Listen and attend, and remember, O Best Beloved; because we know about Tabus, you and I.

When Taffimai Metallumai (but you can still call her Taffy) went out into the woods hunting with Tegumai, she never kept still. She kept very unstill. She danced among dead leaves, she did. She snapped dry branches off, she did. She slid down banks and pits, she did quarries and pits of sand, she did. She splashed through swamps and bogs, she did; and she made a horrible noise! So all the animals that they hunted—squirrels, beavers, otters, badgers, and deer, and the rabbits—knew when Taffy and her Daddy were coming, and ran away.

Then Taffy said, ‘I’m awfully sorry, Daddy, dear.’ Then Tegumai said, ‘What’s the use of being sorry? The squirrels have gone, and the beavers have dived, the deer have jumped, and the rabbits are deep in their buries. You ought to be beaten, O Daughter of Tegumai, and I would, too, if I didn’t happen to love you.’ Just then he saw a squirrel kinking and prinking round the trunk of an ash-tree, and he said, ‘H’sh! There’s our lunch, Taffy, if you’ll only keep quiet.’

Taffy said, ‘Where? Where? Show me! Show!’ She said it in a raspy-gaspy whisper that would have frightened a steam-cow, and she skittered about in the bracken, being a ‘citable child; and the squirrel flicked his tail and went off in large, free, loopy-legs to about the middle of Sussex before he ever stopped.

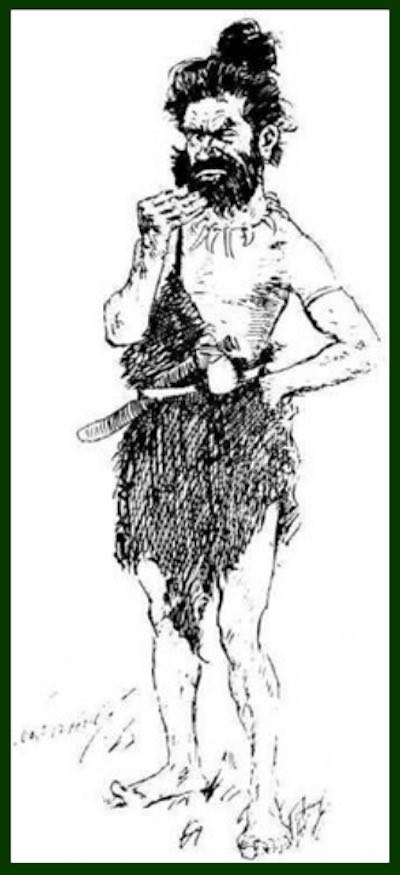

Tegumai was severely angry. He stood quite still, making up his mind whether it would be better to boil Taffy, or skin Taffy, or tattoo Taffy, or cut her hair, or send her to bed for one night without being kissed; and while he was thinking, the Head Chief of the Tribe of Tegumai came through the woods all in his eagle-feathers.

He was the Head Chief of the High and the Low and the Middle Medicine for the whole Tribe of Tegumai, and he and Taffy were rather friends.

He said to Tegumai, ‘What is the matter, O Chiefest of Bopsulai? You look angry.’

‘I am angry,’ said Tegumai, and he told the Head Chief all about Taffy’s very unstillness in the woods; and about the way she frightened the game; and about her falling into swamps because she would look behind her when she ran; and about her falling out of trees because she wouldn’t take good hold on both sides of her; and about her getting her legs all greeny with duckweed from ponds and places, and bringing it sploshing into the Cave. The Head Chief shook his head till the eagle-feathers and the little shells on his forehead rattled, and then he said, ‘Well, well! I’ll see about it later. I wanted to talk to you, O Tegumai, on serious business.’

‘Talk away, O Head Chief,’ said Tegumai, and they both sat down politely.

‘Observe and take notice, O Tegumai,’ said the Head Chief. ‘The Tribe of Tegumai have been fishing the Wagai river ever so long and ever so much too much. Consequence is, there’s hardly any carp of any size left in it, and even the little carps are going away. What do you think of putting the big Tribal Tabu on it, so as to stop every one fishing there for six months?’

‘That’s a good plan, O Head Chief,’ said Tegumai. ‘But what will the consequence be if any of our people break tabu?’

‘Consequence will be, O Tegumai,’ said the Head Chief, ‘that we will make them understand it with sticks and stinging-nettles and dobs of mud; and if that doesn’t teach them, we’ll draw fine, freehand Tribal patterns on their backs with the cutty edges of mussel-shells. Come along with me, O Tegumai, and we will proclaim the Tribal Tabu on the Wagai river.’

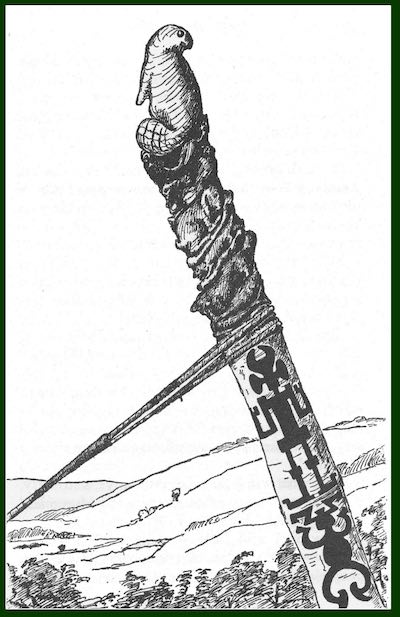

Then they went up to the Head Chief’s head house, where all the Tribal Magic of Tegumai belonged; and they brought out the Big Tribal Tabu-pole, made of wood, with the image of the Tribal Beaver of Tegumai and the other animals carved on top, and all the Tribal Tabu-marks carved underneath.

Then they called up the Tribe of Tegumai with the Big Tribal Horn that roars and blores, and the Middle Tribal Conch that squeaks and squawks, and the Little Tribal Drum that taps and raps.

They made a lovely noise, and Taffy was allowed to beat the Little Tribal Drum, because she was rather friends with the Head Chief.

When all the Tribe had come together in front of the Head Chief’s house, the Head Chief stood up and said and sang: ‘O Tribe of Tegumai! The Wagai river has been fished too much, and the carp-fish are getting frightened. Nobody must fish in the Wagai river for six months. It is tabu both sides and the middle; on all islands and mud-banks. It is tabu to bring a fishing-spear nearer than ten man-strides to the bank of the river. It is tabu, it is tabu, it is most specially tabu, O Tribe of Tegumai! It is tabu for this month and next month and next month and next month and next month and next month. Now go and put up the Tabu-pole by the river, and don’t let anybody pretend that they haven’t understood!’

This is a picture of the Tribal Totem Pole after it was put up on the banks of the Wagai river. That fat thing at the top is the Tribal Beaver of the Tribe of Tegumai. It is carved from lime-wood, and though you can’t see the nails, it is nailed on to the rest of the pole, which is all in one piece. Below the Beaver are four birds—two ducks, one of them looking at an egg, a sparrow–bird, and a bird whose name I don’t know. Below them is a Rabbit, below the Rabbit a Weasel, below the Weasel a Fox or a Dog (I am not quite sure which), and below the Dog two Fishes.

On the other side of the pole is an Otter, a Badger, a Bison, and a Wild Horse. The rope that steadies the pole is looped round next to the Fishes. This shows that the Tabu is a Fish Tabu. If the Head Chief wanted to tabu the tribe killing Rabbits or Duck, he would have put the rope next to the Rabbit or the Duck carving; and so on with the other animals and birds.

The two black figures below the rope are meant for the Bad Man who didn’t keep Tabu, and so grew all knobby and uncomfy, and the Good Man who kept Tabu and grew fat and round. They are painted on the pole with a paint made from oak–apples and pounded–up pieces of iron. At the very bottom of the pole (but there was not room to put it in the picture) are six copper rings to show that the Tabu was to last for six months.

You will see that there is nobody at all in the woods and hills behind. That is because the Tabu is a Strong Tabu and nobody would break it.

Then the Tribe of Tegumai shouted, and put up the Tabu-pole by the banks of the Wagai river, and swiftly they ran down both banks (half the Tribe on one side and half on the other), and chased away all the small boys who hadn’t attended the meeting because they were looking for crayfish in the river; and then they all praised the Head Chief and Tegumai Bopsulai.

Tegumai went home after this, but Taffy stayed with the Head Chief, because they were rather friends. She was very much surprised. She had never seen a tabu put on anything before, and she said to the Head Chief, ‘What does Tabu mean azactly?’

The Head Chief said, ‘Tabu doesn’t mean anything till you break it, O Only Daughter of Tegumai; but when you break it, it means sticks and stinging-nettles and fine, freehand Tribal patterns drawn on your back with the cutty edges of mussel-shells.’

Then Taffy said, ‘Could I have a tabu of my own—a little small tabu to play with?’

Then the Head Chief said, ‘I’ll give you a little tabu of your own, just because you made up that picture-writing, which will one day grow into the ABC.’ (You remember how Taffy and Tegumai made up the Alphabet? That was why she and the Head Chief were rather friends.)

He took off one of his magic necklaces—he had twenty-two of them—and it was made of bits of pink coral, and he said, ‘If you put this necklace on anything that belongs to you your own self, no one can touch that thing until you take the necklace off. It will only work inside your own Cave; and if you have left anything of yours lying about where you shouldn’t, the tabu won’t work till you have put that thing back in its proper place.’

‘Thank you very much indeed,’ said Taffy. ‘Now, what d’you truly s’pose it will do to my Daddy?’

‘I’m not quite sure,’ said the Head Chief. ‘He may throw himself down on the floor and shout, or he may have cramps, or he may just flop, or he may take Three Sorrowful Steps and say sorrowful words, and then you can pull his hair three times if you like.’ ‘And what will it do to my Mummy?’ said Taffy. ‘There aren’t any tabus on people’s Mummies,’ said the Head Chief.

‘Why not?’ said Taffy.

‘Because if there were tabus on people’s Mummies, people’s Mummies could put tabus on breakfasts, and dinners, and teas, and that would be very bad for the Tribe. Long and long ago the Tribe decided not to have tabus on people’s Mummies—anywhere—for anything.’

‘Well,’ said Taffy, ‘do you know if my Daddy has any tabus of his own that will work on me—s’posin’ I broke a tabu by accident?’ ‘You don’t mean to say,’ said the Head Chief, ‘that your Daddy has never put any tabus on you yet?’

‘No,’ said Taffy; ‘he only says “Don’t!” and gets angry.’ ‘Ah! I suppose he thought you were a kiddy,’ said the Head Chief. ‘Now, if you show him that you’ve a real tabu of your own, I shouldn’t be surprised if he put several real tabus on you.’

‘Thank you,’ said Taffy; ‘but I have a little garden of my own outside the Cave, and if you don’t mind I should like you to make this tabu-necklace work so that if I hang it up on the wild roses in front of the garden, and people go inside, they won’t be able to come out until they have said they are sorry.’

‘Oh, certainly, certainly,’ said the Head Chief. ‘Of course you can tabu your very own garden.’

‘Thank you,’ said Taffy; ‘and now I will go home and see if this tabu truly works.’

When she got back to the Cave, it was nearly time for dinner; and when she came to the door, Teshumai Tewindrow, her dear Mummy, instead of saying, ‘Where have you been, Taffy?’ said, ‘O Daughter of Tegumai, come in and eat,’ same as if she had been a grown-up person. That was because she saw a tabu-necklace on Taffy’s neck.

Her Daddy was sitting in front of the fire waiting for dinner, and he said the very same thing, and Taffy felt most important.

She looked all round the Cave, to see that her own things (her private mendy-bag of otter-skin, with the shark’s teeth and the bone needles and the deer-sinew thread; her mud-shoes of birch-bark; her spear and her throwing-stick and her lunch-basket) were all in their proper places, and then she slipped off her tabu-necklace quite quickly and hung it over the handle of the little wooden water-bucket that she used to draw water with.

Then her Mummy said to Tegumai, her Daddy, quite accidental, ‘O Tegumai! Won’t you get us some fresh drinking-water for dinner?’

‘Certainly,’ said Tegumai, and he jumped up and lifted Taffy’s bucket with the tabu-necklace on it. Next minute he fell down flat on the floor and shouted; then he curled himself up and rolled round the cave; then he stood up and flopped several times.

‘My dear,’ said Teshumai Tewindrow, ‘it looks to me as if you had rather broken somebody’s tabu somehow. Does it hurt?’

‘Horribly,’ said Tegumai. He took Three Sorrowful Steps and put his head on one side, and shouted, ‘I broke tabu! I broke tabu! I broke tabu!’

‘Taffy, dear, that must be your tabu,’ said Teshumai Tewindrow. ‘You’d better pull his hair three times, or he will have to go on shouting till evening; and you know what Daddy is like when he once begins.’

Tegumai stooped down, and Taffy pulled his hair three times; and he wiped his face, and said, ‘My Tribal Word! That’s a dreadful strong tabu of yours, Taffy. Where did you get it from?’

‘The Head Chief gave it me. He told me you’d have cramps and flops if you broke it,’ said Taffy.

‘He was quite right. But he didn’t tell you anything about Sign Tabus, did he?’

‘No,’ said Taffy. ‘He said that if I showed you I had a real tabu of my own, you’d most likely put some real tabus on me.’

‘Quite right, my only daughter dear,’ said Tegumai. ‘I’ll give you some tabus that will simply amaze you—Stinging-Nettle Tabus, Sign Tabus, Black and White Tabus—dozens of tabus. Now attend to me. Do you know what this means?’

Tegumai skiffled his forefinger in the air snakyfashion. ‘That’s tabu on wriggling when you’re eating your dinner. It is an important tabu, and if you break it, you’ll have cramps—same as I did—or else I’ll have to tattoo you all over.’

Taffy sat quite still through dinner, and then Tegumai held up his right hand in front of him, the fingers close together. ‘That’s the Still Tabu, Taffy. Whenever I do that, you must stop as you are, whatever you are doing. If you are sewing, you must stop with the needle halfway through the deer-skin. If you’re walking, you stop on one foot. If you’re climbing, you stop on one branch. You don’t move until you see me go like this.’

Tegumai put up his right hand, and waved it in front of his face two or three times. ‘That’s the sign for Carry On. You can go on with whatever you are doing when you see me make that.’

‘Aren’t there any necklaces for that tabu?’ said Taffy.

‘Yes. There is a red-and-black necklace, of course, but how can I come tramping through the fern to give you a Still Tabu necklace every time I see a deer or a rabbit, and want you to be quiet?’ said Tegumai. ‘I thought you were a better hunter than that. Why, I might have to shoot an arrow over your head the minute after I had put Still Tabu on you.’

‘But how would I know what you were shooting at?’ said Taffy.

‘Watch my hand,’ said Tegumai. ‘You know the three little jumps a deer gives before he starts to run off – like this?’ He looped his finger three times in the air, and Taffy nodded. ‘When you see me do that, you’ll know we’ve found a deer. A little jiggle of the forefinger means a rabbit.’

‘Yes. Rabbits run like that,’ said Taffy, and jiggled her forefinger the same way.

‘Squirrel’s a long, climby-up twist in the air. Like this!’

‘Same as squirrels kinking round trees. I see,’ said Taffy.

‘Otter’s a long, smooth, straight wave in the air—like this.’

‘Same as otters swimming in a pool. I see,’ said Taffy.

‘And beaver’s just as if I was smacking somebody with my open hand.’

‘Same as beavers’ tails smacking on the water when they are frightened. see.’

‘Those aren’t tabus. Those are just signs to show you what I am hunting. The Still Tabu is the thing you must watch, because it’s a big tabu.’

‘I can put the Still Tabu on, too,’ said Teshumai Tewindrow, who was sewing deer-skins together. ‘I can put it on you, Taffy, when you get too rowdy going to bed.’

‘What happens if I break it?’ said Taffy. ‘You can’t break a tabu except by accident.’ ‘But s’pose I did,’ said Taffy.

‘You’d lose your own tabu-necklace. You’d have to take it back to the Head Chief, and you’d just be called Taffy again, not Daughter of Tegumai. Or perhaps we’d change your name to Tabumai Skellumzulai—the Bad Thing who can’t keep a Tabu—and very likely you wouldn’t be kissed for a day and a night.’

‘Umm!’ said Taffy. ‘I don’t think tabus are fun at all.’ ‘Well, take your tabu-necklace back to the Head Chief, and say you want to be a kiddy again, O Only Daughter of Tegumai!’ said her Daddy. ‘No,’ said Taffy. ‘Tell me more about tabus. Can’t I have some more of my very own—my very own—strong tabus that give people Tribal Fits?’

‘No,’ said her Daddy. ‘You aren’t old enough to be allowed to give people Tribal Fits. That pink necklace will do quite well for you.’

‘Then tell me more about tabus,’ said Taffy.

‘But I am sleepy, daughter dear. I’ll just put tabu on anyone talking to me till the sun gets behind that hill, and we’ll go out in the evening and see if we can catch rabbits.

Ask Mummy about the other tabus. It’s a great comfort that you are a tabu-girl, because now I shan’t have to tell you anything more than once.’

Taffy talked quietly to her Mummy till the sun was in the right place. Then she waked Tegumai, and they both got their hunting things ready and went out into the woods. But just as she passed her little garden outside the Cave, Taffy took off her tabu-necklace and hung it on a rose-bush. Her garden-border was only marked with white stones, but she called the Rose the real gate into it, and all the Tribe knew it.

‘Who do you s’pose you’ll catch?’ said Tegumai. ‘Wait and see till we come back,’ said Taffy. ‘The Head Chief said that anyone who breaks that tabu will have to stay in my garden till I let him out.’ They went along through the woods, and crossed the Wagai river on a fallen tree, and they climbed up to the top of a big bare hill where there were plenty of rabbits in the fern.

‘Remember you’re a tabu-girl now,’ said Tegumai, when Taffy began to skitter about and ask questions instead of hunting for rabbits; and he made the Still Tabu sign, and Taffy stopped as if she had been all turned into one solid stone. She was stooping to tie up a shoestring, and she stayed still with her hand on the string (We know that kind of tabu, don’t we, Best Beloved?) only she looked hard at her Daddy, which you always must do when the Still Tabu is on. Presently, when he had walked a long way off, he turned round and made the Carry On sign. So she walked forward quietly through the bracken, always looking at her Daddy, and a rabbit jumped up in front of her. She was just going to throw her stick, when she saw Tegumai make the Still Tabu sign, and she stopped with her mouth half open and her throwing-stick in her hand. The rabbit ran towards Tegumai, and Tegumai caught it. Then he came across the fern and kissed his daughter and said, ‘That is what I call a superior girldaughter. It’s some pleasure to hunt with you now, Taffy.’

A little while afterwards, a rabbit jumped up where Tegumai couldn’t see it, but Taffy could, and she knew it was coming towards her if Tegumai did not frighten it; so she held up her hand, made the Rabbit Sign (so as he should know she wasn’t in fun), and she put the Still Tabu on her own Daddy! She did—indeed she did, Best Beloved!

Tegumai stopped with one foot half lifted to climb over an old tree-trunk. The rabbit ran past Taffy, and Taffy killed it with her throwing-stick; but she was so excited that she forgot to take off the Still Tabu for quite two minutes, and all that time Tegumai stood on one leg, not daring to put his other foot down. Then he came and kissed her and threw her up in the air, and put her on his shoulder and danced and said, ‘My Tribal Word and Testimony! This is what I call having a daughter that is a daughter, O Only Daughter of Tegumai!’ And Taffy was most tremenenssly and wonderhugely pleased.

It was almost dark when they went home. They had five rabbits and two squirrels, as well as a water-rat. Taffy wanted the water-rat’s skin for a purse. (People had to kill water-rats in those days because they couldn’t buy purses, but we know that water-rats are just as much tabu, these particular days, for you and me as anything else that is alive.)

‘I think I’ve kept you out a little too late,’ said Tegumai, when they were near home, ‘and Mummy won’t be pleased with us. Run home, Taffy! You can see the Cave-fire from here.’

Taffy ran along, and that very minute Tegumai heard something crackle in the bushes, and a big, lean, grey wolf jumped out and began to trot quietly after Taffy.

Now, all the Tegumai people hated wolves and killed them whenever they could, and Tegumai had never seen one so close to his Cave before.

He hurried after Taffy, but the wolf heard him, and jumped back into the bushes. Those wolves were afraid of grown-ups, but they used to try and catch the children of the Tribe. Taffy was swinging the water-rat and singing to herself—her Daddy had taken off all tabus—so she didn’t notice anything.

There was a little meadow close to the Cave, and by the mouth of the Cave Taffy saw a tall man standing in her rose-garden, but it was too dark to make out properly.

‘I do believe my tabu-necklace has truly caught somebody,’ she said, and she was just running up to look when she heard her Daddy say, ‘Still, Taffy! Still Tabu till I take it off!’ She stopped where she was—the water-rat in one hand and the throwing-stick in the other—only turning her head towards her Daddy to be ready for the Carry On sign.

It was the longest Still Tabu she had had put upon her all that day. Tegumai had stepped back close to the wood and was holding his stone throwing-hatchet in one hand, and with the other he was making the Still Tabu sign.

Then she thought she saw something black creeping sideways at her across the grass. It came nearer and nearer, then it moved back a little and then it crawled closer.

Then she heard her Daddy’s stone throwing-hatchet whirr past her shoulder just like a partridge, and at the same time another hatchet whirred out from her rose garden; and there was a howl, and a big grey wolf lay kicking on the grass, quite dead.

Then Tegumai picked her up and kissed her seven times and said, ‘My Tribal Word and Tegumai Testimony, Taffy, but you are a daughter to be proud of. Did you know what it was?’

‘I’m not sure,’ said Taffy. ‘But I think I guessed it was a wolf. I knew you wouldn’t let it hurt me.’

‘Good girl,’ said Tegumai, and he stooped over the wolf and picked up both hatchets. ‘Why, here’s the Head Chief’s hatchet!’ he said, and he held up the Head Chief’s magic throwing-hatchet, with the big greenstone head.

‘Yes,’ said the Head Chief from inside Taffy’s rosegarden, ‘and I’d be very much obliged if you would bring it back to me. I came to call on you this afternoon, and accidentally I stepped into Taffy’s garden before I saw her tabu-necklace on the rose-tree. So, of course, I had to wait, till Taffy came back to let me out.’

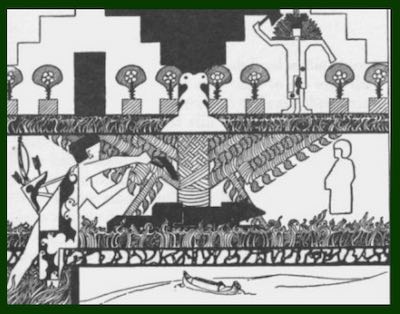

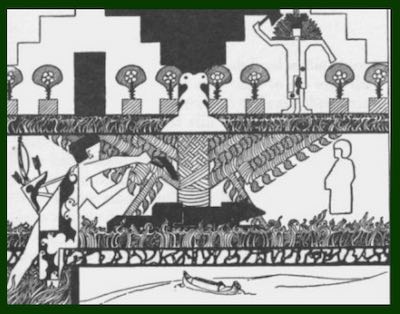

This is the picture that the Head Chief made of Taffy keeping the Still Tabu. It is done in the Head-Chiefly style of the Tribe of Tegumai, and it is full of Tabu meanings and signs. The wolf is lying under what is meant to be a Tabu tree. He is made squarely because that was the Head Chiefly way of drawing. All that wavy curly stuff underneath hiin is the Tabu way of drawing grass, and below the grass is a thing like a piece of stone wall, which is the Tabu way of drawing earth.

Taffy is always drawn in outline—quite white. You will see her over to the right, keeping the Still Tabu very hard. I do not know why they did not draw the water-rat that she was carrying, but I think it was be cause it wouldn’t look pretty in the picture.

Tegumai is standing over at the left, throwing his hatchet at the wolf. He is dressed in a cloak embroidered with the Sacred Beaver of the Tribe all turned into a pattern, to show that he belonged to the Tribe of Tegumai. He has a quiver with two arrows and a bow stuck into it, to show that he is hunting. He is making the Still Tabu sign with his left hand.

Up above in the right-hand corner you will see the Head Chief standing in Taffy’s garden, throwing his axe at the wolf. It is not a portrait of the Head Chief, but a sort of picture-writing of all the Head Chief there was. The square cap and the feathers behind show that it is a Head Chief, and the Sacred Beaver drawn on the edge of his cloak shows that he is the Head Chief of the Tegumais. There is no face, because the face of a Head Chief does not matter.

The Double-Headed Beaver right in the middle of Taffy’s garden shows that there is a Tabu on the garden; which is why the Head Chief couldn’t get out. The black door to the left is supposed to be the door into Taffy’s cave, and those step’things behind are hills and rocks drawn in the Tabu way. The curly things under the eight roses in pots are the Tabu way of drawing short grass and turf.

This is a picture that really ought to be coloured, because half the meaning is lost without the colours.

Then the Head Chief all in his feathers and shells took the Three Sorrowful Steps with his head on one side, and said, ‘I broke tabu! I broke tabu! I broke tabu!’ and bowed solemnly and statelily before Taffy, till his tall eagle-feathers nearly touched the ground, and he said and he sang, ‘O Daughter of Tegumai, I saw everything that happened. You are a true tabu-girl. I am very pleased at you. At first I wasn’t pleased, because I had to wait in your garden since six o’clock, and I know you only put tabu on your garden for fun.’

‘No, not fun,’ said Taffy. ‘I truly wanted to see if my tabu would catch anybody; but I didn’t know that a little tabu like mine would work on a big Head Chief like you, O Head Chief.’

‘I told you it worked. I gave it to you myself,’ said the Head Chief. ‘Of course it would work. But I don’t mind. I want to tell you, Taffy, my dear, that I wouldn’t have minded staying in your garden from twelve o’clock instead of only six o’clock to see how beautifully you kept that last Still Tabu that your Daddy put on you. I give you my Chiefly Word, Taffy, that a great many men in the Tribe wouldn’t have kept that tabu as you kept it, with that wolf crawling up to you across the grass.’

‘What are you going to do with the wolf-skin, O Head Chief?’ said Tegumai, because any animal that the Head Chief threw his hatchet at belonged to the Head Chief by the Tribal Custom of Tegumai.

‘I am going to give it to Taffy, of course, for a winter cloak, and I’ll make her a magic necklace of her very own out of the teeth and claws,’ said the Head Chief; ‘and I am going to have the story of Taffy and the Still Tabu painted on wood on the Tribal Tabu-Count, so that all the girl-daughters of the Tribe can see and know and remember and understand.’

Then they all three went into the Cave, and Teshumai Tewindrow gave them a most beautiful supper, and the Head Chief took off his eagle-feathers and all his necklaces; and when it was time for Taffy to go to bed in her own little cave, Tegumai and the Head Chief came in to say good-night, and they romped all round the cave, and dragged Taffy over the floor on a deer-skin (same as some people are dragged about on a hearth-rug), and they finished by throwing the otter-skin cushions about and knocking down a lot of old spears and fishing-rods that were hung on the walls. At last things grew so rowdy that Teshumai Tewindrow came in, and said, ‘Still! Still Tabu on every one of you! How do you ever expect that child to go to sleep?’ And they said the really good-night, and Taffy went to sleep.

After that, what happened? Oh, Taffy learned all the tabus just like some people we know. She learned the White Shark Tabu, which made her eat up her dinner instead of playing with it (and that goes with a green-and-white necklace, you know); she learned the Grown-Up Tabu, which prevented her from talking when Neolithic ladies came to call (and, you know, a blue-and-white necklace goes with that); she learned the Owl Tabu, which prevented her staring at strangers (and a black-and-blue necklace goes with that); she learned the Open Hand Tabu (and we know a pure white necklace goes with that), which prevented her snapping and snarling when people borrowed things that belonged to her; and she learned five other tabus.

But the chief thing she learned, and the one that she never broke, not even by accident, was the Still Tabu. That was why she was taken everywhere that her Daddy went.

Here is a PDF version of the story

All the illustrations were drawn by Rudyard Kipling himself!